Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

A many-splendored thing 7: Li Han-hsiang

Enchanting Shadow.

A classic storyteller, in suitable surroundings

Film director Li Han-hsiang didn’t benefit from the 1980s-1990s explosion of interest in Hong Kong cinema. For one thing, most of his films were for Shaw Brothers, and those were hard to find on video. For another, Li worked in genres that didn’t attract many fanboys and fangirls. As a result, he’s not as well known as his Shaws compadres Chang Cheh, King Hu, and Lau Kar-leung.

Although opinions about his directorial skills vary, there’s no denying his historical importance. Besides making over 100 films, Li both shaped and reflected several trends in local cinema. A massive retrospective of his work has begun at the Hong Kong Film Archive during the festival, and it will continue well into May.

While several of Li’s films are now available on DVD through the Celestial library, the retrospective features many titles that are hard to see, and it samples the range of this important director’s career.

Li’s breakthrough came in the huangmei diao genre, the “yellow plum” opera. These operetta-like films tended to center on romantic tales of court life, often involving ill-fated lovers. Li’s Diau Charn (1958), The Kingdom and the Beauty (1959), and The Love Eterne (1963) helped define the huangmei picture. The films became flagship Shaws vehicles, showcasing vast sets, eye-searing color, and sweet music, and they won praise at Asian film festivals. Spurred by his success, Li went independent. He relocated to Taiwan and continued to make lavish costume dramas, most notably the two-part Beauty of Beauties (1966).

His gamble failed, and Li returned to Shaws to make The Warlord (1972), with Michael Hui. As Shaws began to pursue more sensational fare, Li proved surprisingly adept at erotic films and films about gambling. He returned to the costume drama too, as in The Dream of the Red Chamber (1977), with Brigitte Lin playing a male role (heard that before?). Li’s biopic of Emperor Puyi, titled The Last Emperor (1986), beat Bertolucci’s project to the screen.

Li also made small-scale films about local neighborhood life, like Rear Entrance (1960), and during his Taiwan stay he explored understated melodrama too. Clearly, a retrospective is overdue, and the Archive has done it up right.

The screenings run until 25 May. Along with the films, there’s a handsome book, Li Han-hsiang, Storyteller. It features in-depth essays, many interviews, and an annotated filmography. (I don’t find the book listed for sale on the Archive’s website, but its price is HK$128, and general ordering information is here.) The archive is presenting an exhibition of costumes and props from the films, including lingerie worn by one female star.

The Dream of the Red Chamber (1977).

I had little to say about Li in Planet Hong Kong because in the late 1990s the Shaws collection was inaccessible and I was able to see only a few of Li’s works properly. The titles shown at earlier editions of the HKIFF were certainly impressive, notably Enchanting Shadow (1960), based on the same story that is the source for A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), and the costume extravaganza Beauty of Beauties. Still, I thought that Li lacked the filmmaking élan of his friend King Hu.

I’ve now seen several more Li titles, and though I see no reason to revise my first impression, I’ve come to appreciate his distinctive virtues more. He’s by and large a woman-centered filmmaker, and his female protagonists tend to be energetic and enterprising. The Love Eterne is particularly interesting in its endorsement of women’s ambitions. I haven’t seen evidence that Li has a distinctive approach to staging or cutting, as some other Shaws directors do. His emphasis falls upon settings and costumes, presented in vivid color schemes and captured in graceful widescreen compositions.

Here are some thoughts on what I’ve watched in the series here.

Flower Drums of Fung Yang (1967): One of Li’s Taiwan pictures, this centers a young woman who, after being raped by bandits, takes up street performing. Trouble comes in the form of her husband, who resents her ability to support the two of them, and a rival singing troupe. The musical score consists of a single song played in a variety of moods. The standard conceit of a woman pretending to be a man enhances a sad tale of the hopelessness of women’s lot—a common Li theme.

The Winter (1969): The best of the Li’s I’ve seen in this go-round. Our hero is a shy restaurant-owner who can’t bring himself to admit he loves the girl next door. Simple and poignant, shot largely on location in a teeming street market, the film is unusually quiet for Li, and he displays resourceful use of the anamorphic ratio. The film has become a classic of Taiwanese cinema, and Tony Rayns tells me that its understated realism influenced Hong Kong’s New Wave generation of the 1970s.

Four Moods (1970): An episode film. I had seen the King Hu contribution, Anger, several times before, and it’s still the best in the quartet. Li’s own contribution, Happiness, is a story about a miller and the ghost he meets while fishing. Amiable, somewhat confusing in its attitude toward the miller’s daughter, this wouldn’t convince you that Li was a good director.

The Burning of the Imperial Palace (1982): Li was given the rare opportunity to film in Beijing’s Forbidden City, and he took full advantage of it: The pageantry of his splendid long shots makes today’s greenscreen vistas look insubstantial. But as Wallace Kwong explains in his essay in the Archive anthology, Li’s mainland collaborators demnded many changes in the storyline.

The film traces the rise to power of the girl Cixi, recruited to the young emperor’s harem and eventually becoming a rival to his wife. In elaborate, rapidly edited sequences, Li tells a captivating story of a weak ruler (played by a very young Tony Leung Ka-fai) and the strong women behind him, who are ready to strike deals with Western imperialists.

Reign behind the Curtain (1983): A continuation of Burning, and another engaging palace intrigue. The emperor fritters his kingdom away while Cixi produces a male heir and enters into a tactical alliance with the empress. After his death, the two women struggle with the eight-man advisory council, and eventually with each other. Cixi has turned from an innocent girl into a Machiavellian power-broker, all adding to the woes of China. Like its prequel, a gripping story and skilful performances.

Five rather different films! I look forward to more.

A home for Hong Kong films

When I first came to Hong Kong in 1995, the Archive was housed in a trailer. Now it has a lovely building in the tranquil neighborhood of Sai Wan Ho. The light, airy lobby boasts posters and an exhibition hall, currently illustrating the Li retrospective.

Law Kar has been a key player in preserving and interpreting the local film heritage. He went to school with John Woo and founded some of the first local university film societies. An important critic, he oversaw many of the festival publications that provided gweilos like me precious information. He has also written a fine book with Frank Bren on early HK film history. Recently retired as the archive’s Head Programmer, he still turns out for events, and I’m always happy to see him.

There’s a hiatus in the Li screenings for a couple of days, so I’ll post this now and catch up with other films in a later entry.

Betty Lo Tih in Enchanting Shadow.

A many-splendored thing 6: Tourist interlude

Hong Kong island, seen from the harbor.

Tourist images, plus a tribute to Gor-Gor

I thought I’d use one blog to squeeze together some tourist views that I snapped since my arrival for the Hong Kong International Film Festival on 17 March. I never get tired of looking at, and photographing, this amazing city. For you film geeks, I’ve added a coda on a sad movie topic.

Hong Kong consists of Hong Kong island, some other outlying islands, and the Kowloon peninsula, plus the New Territories north of Kowloon. You can shuttle between the main island and the peninsula by taxi, by subway, or by ferry. Like many locals and most tourists, I prefer the ferry because it yields gorgeous views like the one above.

But the ferry to the Central area of Hong Kong island has been redirected. The old terminal has been closed so that more land can be reclaimed from the harbor for highways and skyscrapers. A new, Disneyfied terminal has been erected in its place further down the shore. It looks like cardboard in daylight but can be pretty at night.

Still, the old terminal wasn’t given up without protest.

In front of the old terminal, where City Hall stands, there used to be lots of people hanging out. Now the place is largely empty because of all the construction. What remains are the metal silhouettes sitting, mobilephoning, and practicing tai chi.

A city devoted to shopping, Hong Kong has its own equivalent of the medieval cathedral: the shopping mall. Festival Walk, one of the biggest, has a large ice rink. Here’s one of my favorites, some of the twelve floors of the Times Square mall. But why is Lane Crawford everywhere here? What is Lane Crawford?

Grandiosity doesn’t afflict only mall architecture. The Bank of China, designed by I. M. Pei, was the biggest thing going when I first came in 1995. Now it’s dwarfed by Two International Finance Centre (in the right foreground at top of entry), which looks like the box the Bank came in. Pei’s zigzag symmetries and asymmetries are still mighty impressive, though.

In my neighborhood, Yau Ma Tei in Kowloon, the new construction thrusts ever higher. This is a view from the twelfth floor of my hotel.

Later this year west Kowloon will house a building 60 meters higher than the International Finance Centre. It will be, at least for a time, the tallest building in the world. Even multi-bean snacks start to look monumental here.

On the bus, things shrink to a more human scale. This is from my daily ride down Nathan Road to the Cultural Centre and the ferry. Two International Finance Centre is dimly visible in the left distance.

One movie note: Today was the fourth anniversary of the death of Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, who committed suicide at the Mandarin Hotel in Central. He was one of Hong Kong’s most popular stars, seen in Days of Being Wild, Happy Together, A Chinese Ghost Story, He’s a Woman She’s a Man, and many other classics. Every year fans erect floral tributes along the sidewalk.

Thanks to Akiko Tetsuya and Yvonne Teh for guiding me to this moving display.

So much for tourism. Next time, back to the festival.

A many-splendored thing 5: Sampling

Sakuran.

From DB:

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

Current chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, Beijing’s appointee, won the election, with 649 votes out of 789 voting members. Tsang has promised to introduce direct voting and universal suffrage by 2012. We’ll see.

The other big story has been the aftermath of a 2006 shootout involving police constable Tsui Po-ko. The latter has the confusing intricacy of a Hong Kong cop movie. Some years ago Tsui allegedly killed another cop and stole his pistol; a year later he robbed a bank. (The Economist offers a summary here.) An inquest has been under way. Wednesday’s South China Morning Post (not available free online) reports on the contents of Constable Tsui’s notebooks. There are indications that he was tailing political figures and calculating how an ambush might be carried out beneath traffic underpasses.

The media have gone wild over this and even replayed the episode of the local version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? on which Tsui appeared as a contestant. Today’s edition of the SCMP reports an even weirder turn. An FBI expert has testified that Tsui suffered from schizotypal personality disorder. This is characterized by “social isolation, odd behavior and thinking, and often unconventional beliefs.” Sound like you or me?

Moving to the more comforting world of cinema, let me catch up on some of the films I’ve seen at Filmart and the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Ying Liang’s The Other Half: A shrewdly constructed story about a young woman with marital troubles who becomes a legal stenographer. Ying interweaves her life crises with the monologues of locals who come to seek action from the lawyer. These incidents were derived, Ying explained in the Q & A, from actual cases the non-actors knew. Ying collected over 100 law cases and then showed his script to lawyers and legal professionals, some of whom appeared in the film. Single-take scenes predominate, making good use of the deep-focus capacities of digital video. A vivid angle into ordinary life in China, with insights as well into problems of industrial pollution.

Li Yu’s Lost in Beijing: Less interesting, I thought. A fairly traditional melodrama involving an innocent woman caught between two macho men, husband and boss, and the boss’s scheming wife. The glimpses of life in Beijing were more valuable than the supposedly scandalous sex scenes that feature heavily in the early reels.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Daniel Wu plays an undercover cop who’s taken years to become virtually a son to drug kingpin Andy Lau. Their intriguing relationship counterbalances Yu’s efforts to wean an addicted mother off the stuff. There are some fascinating quasi-documentary scenes of cooking heroin and harvesting Thai poppies. The parallels between the drug addicts whom Andy despises and his own need for shots of insulin are insinuated, not slammed home. Yee mixes grim realism with some showy melodrama, adding an explosive drug bust. (That sequence contains a startling shot that in itself justifies the existence of CGI.) Despite an overlong denouement and a few loose ends, the film seems to me better than the average local genre fare.

Ninagawa Mika’s Sakuran: Anachronism has a field day in this story of a cunning girl’s rise to be top geisha. Riotous sets and costumes, along with big-band swing music, create the suffocating but ravishing world of courtesans and their patrons. A sentimental ending telegraphed far in advance, but no less welcome for that.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Benoît Delépine and Gustave Kervern’s Avida: Black and white almost throughout, in 35mm that looks like muddy 16, this surrealist pastiche starts strong. Early scenes offer a new riff on Tati’s Mon Oncle, in which a toff returns to his cyberautomated mansion and encounters problems with dogs and plate glass. Then we’re in Buñuel-Carrière territory (Carrière is in the movie), as a dognapping leads to an amazing scene of pooch decapitation. Things seemed to me to drag as the episodes got sillier and less visually expressive. Rhinos, lions, elephants, big beetles, and a highly diverse sampling of the human species do walk-ons. Not so much metaphysical as pataphysical.

Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution: A documentary on the pre-1990s Iranian cinema. It’s informative, cautious about the role of the mullahs, and filled with intriguing clips from Hollywood-style melodramas and the neorealist-flavored efforts of the 1970s. Good talking heads too (though no Kiarostami). The film reaffirms how single-mindedly the cinema agencies pursued film festivals as a way of increasing the profile of the nation’s culture; the motto was “No festival without an Iranian film.” But can Iran really have trained a total of 90,000 film-related workers, as the docu says?

Johnnie To’s Exiled: I hadn’t yet seen it on the big screen. That’s where it belongs. The first sequence evokes Once Upon a Time in the West‘s opening, and it’s followed by an exhilarating, utterly implausible gun battle. Watch out for that spinning door!

When Mr. To previewed this opening for me last spring, I didn’t think he could top it, but he does. The later scene in the underground clinic will rank with one of the great action sequences of all time. I won’t spoil it for those who haven’t seen it by previewing a still. Let’s just say that To finds fresh compositional tactics in close quarters, as in the hotel climax.

Full of visual invention and neat character bits, Exiled shows that To keeps trying new things. I wrote a little about To’s style in an earlier post, and some backstory on the Exiled rooftop sets can be found here.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

The cop trembles under the pressure of his own torments, and the parallels between the two men climax in a knife fight in a crumbling Thai temple. As is often the case in local cinema, Father is to blame. This visceral movie surely couldn’t be released theatrically in the US. Even the most jaded action aficionado is likely to flinch from certain scenes.

Cheang’s previous film is the suspenseful Love Battlefield. Of Dog Bite Dog he remarked, “I wanted to show [the audience] this Hong Kong film that does not have choreographed action.” For more, see Grady Hendrix’s coverage here and Twitchfilm’s longish review.

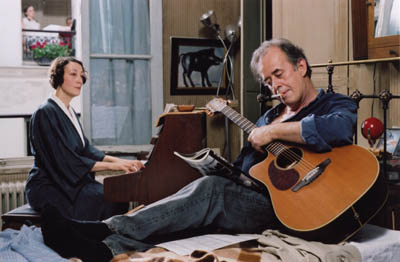

Otar Iosseliani’s Gardens in Autumn: The first shot, in which old men quarrel over which one gets to buy a cheap coffin, puts us firmly in Iosseliani’s parallel universe. As often, he speaks for those who just opt out. A minister of agriculture loses his post and drifts among ne’er-do-well pals, hookers, and girlfriends. A film about drinking, eating, smoking, rollerblading, music-making, and middle-aged sex, Gardens in Autumn also satirizes the rich, who are just as lazy as our heroes but waste their lives shopping. There are also prop gags, including the pictures of heifers and boars that show up in quite unexpected places.

Iosseliani casts himself as an easygoing gardener who draws cartoons on a cafe wall. Some of these images recall people and shots we see in the movie, as if we’re watching the old buzzard create the film between swigs of vodka. An elegiac poem to the subversive force of idleness, with a final scene celebrating women.

Over the next couple of weeks, more frequent posts, I hope, including glimpses of this highly photogenic city. For the moment, this from a double-decker bus must suffice.

A many-splendored thing 3: Filmart and filmfans

The annual Hong Kong Filmart is a trade show for all aspects of film/TV production and distribution. As in past years it commands several floors of the Convention and Exposition Center, shown in yesterday’s entry. There are many screenings (thinly attended) but the main business is dealing. Representatives from Europe and Asia meet and greet in their display spaces, or more often in restaurants and hotel rooms. Here are some snapshots from the floor of the market, which I managed to visit on Wednesday.

The cheerful Park Jiyin gave me some publications and DVDs from the Korean Film Council. She had read Film Art in her university courses!

Sanrio’s display areas were pretty nifty.

On the Filmart floor I again ran into King Wei-chu, brandishing yet another of his poster treasures while we talked with Ip File, a publicity executive for Celestial Pictures (current owners of the Shaw film library). Mr. Ip also worked as an assistant director to Chor Yuen, one of the best Hong Kong directors of the 1950s-1970s.

After cruising Filmart I caught the trade screening of Twins Mission, a goofy but likeable Hong Kong film by martial arts choreographer Kong Tao-hoi. Twins, in case you don’t know, are, or is, a pair of girl pop singers who have made some films before this, notably The Twins Effect (2003). In this entry, Twins are now trapeze artists, and they encounter a squad of kung-fu killers, all themselves either male or female twins. It’s gradually revealed that our Twins were trained in the martial arts along with many other twins…by kung-fu masters who are twins. Confused yet? Given that our Twins don’t resemble one another, the premise seems a sendup of the very idea of twins and, er, Twins.

The agreeable fight sequences are enhanced by digital effects; my favorite passage includes a moment when a spinning blade trims one girl’s eyelashes. There’s a mawkish subplot about a little kid with cancer, but the presence of Sammo Hung and Yuen Wah, who literally plays his own evil twin, more than makes up for it.

A sequel seems already to be shot. This movie, released about a month ago, ends without resolving the plot, and then we’re asked to watch out the rest of the story. Maybe the next installment will develop the subplot involving Sam Lee overacting as a mainland cop, a trail that leads nowhere here. Morever, the 35mm print I saw jumped from scarily sharp HD footage (every pore on the face all too crisp) to fairly poor digitized stuff to soft, sometimes out-of-focus 35 footage. Did they change formats partway through the shoot?

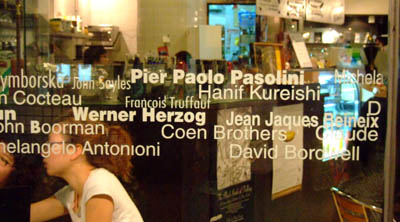

Yes, I learned later that night. I met Grady Hendrix and Goran Topalovic, directors of the New York Asian Film Festival (aka Subway Cinema), for drinks at the movie-themed coffeeshop/ bookstore Kubrick. They bought books, I bought books, then we sat outside chatting. Soon Ryan Law joined us. Ryan has recently expanded the server for the Hong Kong Movie Database, of which he’s the founder and mainstay.

Ryan, Grady, and Goran

Ryan said that for reasons of economy, it’s become very common for HK movies to mix analog and digital formats. He said that in fact Twins Mission used film, HD, and Betacam!

Leisurely talk on a balmy spring night was a good ending to a full but unhurried day, and I came back to write the blog you see now. Tomorrow: more film viewing and a visit to a night shoot of Johnnie To’s installment of Triangle.