Archive for the 'Directors: Spielberg' Category

Stepping into a movie

KT here-

This past weekend I returned from a tour of ancient sites in Jordan. I didn’t plan to see any movies during the trip, but in a way it was a movie that sent me there.

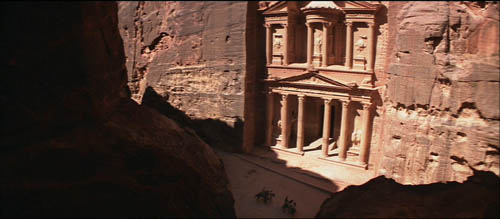

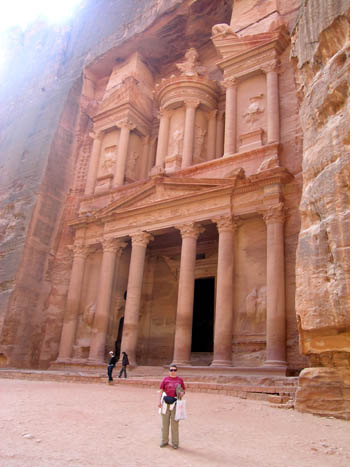

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

That’s not a set. It was shot at Petra in southern Jordan. The canyon is real. It’s called the Siq (“shaft” in Arabic), and it’s a dramatic crack that runs for about a mile between tall, undulating cliffs of red sandstone (on the lower layers, where most of the city’s buildings were carved) and white sandstone (on the upper layers). The other structures include a theater, temples, and many tombs.

As I learned a bit more about Petra as a real place, I conceived an ambition to visit it—not for its Indiana Jones connection but because it is such an extraordinary archaeological site. In fact, last year it was voted one of the new seven wonders of the world.

I was one of seven members of a London-based tour, plus our lecturer and local guide. There are many ancient sites in Jordan, but Petra was left until the end. What, after all, could hope to follow it and not seem a let-down?

No, I didn’t go to see movies, but I discovered it’s pretty hard to escape them. References and connections tend to pop up.

We approached the entrance to Petra through the usual rows of souvenir and refreshment stalls. Some entrepreneurs were exploiting the Indiana Jones connection. Images from posters adorned coffee shops, and more than one shop had hats on sale. They weren’t really much like the famous felt fedora, being mostly of leather and not quite the right shape.

Right beside the Indiana Jones stalls, there was the Titanic Coffee Shop. My companions were mystified as to why anyone would choose that name. To me it seemed pretty obvious. American movies are popular, and why not name your shop after the most popular of them all? There was a restaurant near our hotel called Mystic Pizza. I didn’t see any images from the film on the outside, and I didn’t go inside to find out if there were any there.

Back in early October I reported on Captain Abu Raed, reportedly the first fiction feature made in Jordan in fifty years. There doesn’t seem to be any big stigma against films, though. I saw theaters and video-rental shops, some of the latter adorned with unlicensed paintings of Mickey Mouse.

Our last stop after Petra before returning to Amman was the Wadi Rum (below), an austerely beautiful landscape of desert and small, craggy mountains. The film motif followed us. Part of Lawrence of Arabia was shot there. On the spot where the real Lawrence had trod, the real Peter O’Toole sang, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

They’re looking for us

DB again:

Perhaps you consider Music and Lyrics (2007) a bit of fluff. Bear with me. Apart from offering an ingratiating parody of 1980s music videos, which at the end gets replayed as a parody of 1990s Pop-Up Video, this movie provides a nice example of a technique that film viewers tend to enjoy.

Alex Fletcher, a has-been pop singer, gets a chance to revive his career by writing a love song for Cora Corman, current goddess of teenyboppers. Alex can dash off a melody but he needs a lyricist. His agent has advised him to try to collaborate with the “very hip, very edgy” Greg Antonsky. Their first meeting doesn’t go well. Greg’s lyrics, rhyming witch and bitch, don’t suit Alex’s more romantic style, and Sophie, Alex’s plant-tender, keeps interjecting sweeter lines. After first eyeing Sophie lecherously, Greg decides she’s a simpleton. He dashes out, condemning Sophie and Alex as sentimental fools: “You people disgust me!”

As written, the character of Greg the lyricist is only mildly funny, but the insert shots of actor Jason Antoon raise the comedy thermostat. With his lowered brow and glaring, slightly unfocused eyes, Greg tries to play the badass, but his aggressiveness comes off as egotistical pettiness.

The cutting relies on single shots of each character, in keeping with today’s style of intensified continuity editing. This ensures that we track every character’s facial expression. When Sophie first interrupts, Greg glares, then lolls his head backward; his time is too important to spend with these losers.

In all, Greg is onscreen for about three minutes, and the plot continues without him.

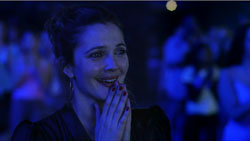

Eventually, Alex and Sophie break up because Alex is prepared to let Cora turn their song into a sleazy number. The climax comes at Cora’s concert, when Alex appears onstage and sings a tune he composed for Sophie: “Don’t Write Me Off.” At the song’s close, we get a shot of him at the piano followed by several reaction shots in the audience, with Sophie’s close-up favored.

After a backstage reconciliation between Alex and Sophie, the film’s second plotline is resolved. Cora performs the number she asked the team to compose, but it’s played the way Sophie had wanted. The up-tempo melody brings Alex and Cora onstage together and then, as the third verse begins, ties together the secondary characters in a series of reaction shots. We first see an African-American backstage handler, whose vigorous swipe of his arm launches a string of smiling responses.

We get shots of Alex’s agent and his daughter, then Sophie’s brother-in-law and his son, and Sophie’s sister and their kids.

Their responses celebrate both the romantic couple’s success and the sincere emotion that the song elicits. This aura of good feeling is confirmed negatively by one more reaction shot.

It is the sort of satisfying surprise that Hollywood often trades on. After being offscreen and out of mind for eighty minutes, arrogant Greg returns. We didn’t see him come to the concert; we didn’t know he was there; we had likely forgotten he existed.

This shot is agreeable because it keeps Greg’s sourness consistent. A more kindly film would show him smiling begrudgingly, won over by the authentic sweetness of the music. But instead he mimics blowing his brains out and lolls his head back as he did before.

Greg’s appalled reaction to the song confirms our initial judgment of his character and our sense of the song’s unpretentious sincerity.

If you’re like me, this unexpected four-second shot makes you laugh. The director, Marc Lawrence, has followed tradition by including humor in a scene of high sentiment, not diluting the happy tone but reinforcing it. Call it corn, hokum, or tosh; claim that it hits below the belt. I won’t disagree. But the mixture of laughter and sentiment works on us like a reflex. And Greg’s response inoculates the movie against seeming wholly naive or cloying. As so often, Hollywood lets us have things, emotionally speaking, both ways.

This response is accomplished through one of the most powerful weapons in the filmmaker’s arsenal. A director can disarm our emotions through a single reaction shot.

Recoil and reaction

The same sort of dynamic is at work in a less lightweight scene. Everybody remembers the moment in Jaws when Sheriff Brody, scooping chum over the side of the Orca, is taken unawares by the arrival of Bruce the shark, bursting out from the background.

But Spielberg, who understands audience response, follows this nifty shot with a topper. In a reverse-angle framing, Brody’s head snaps into the shot with the abruptness of Wile E. Coyote reacting to the Road Runner.

The sudden thrust and halt of Brody’s head sells his stunned facial expression. Our shock at Bruce’s entrance is joined by our uncontrollable urge to giggle at Brody’s cartoonish trajectory and the sheer stupefaction on his face—not fear yet, but rather a recognition of the sheer enormity of the adversary. From here on, his refrain, “We’re gonna need a bigger boat,” will remind us that unlike his shipmates, he has been very nearly head to head with the Great White.

The reaction shot seems like a simple technique. Doesn’t it just spell out or repeat what’s happening? Sometimes, but not always. As we’ve just noticed, it can let the director layer the effect of a scene. Once an action has gained a particular emotional coloring, the reaction shot can add a different tint. The romantic exhilaration of the song in Music and Lyrics is heightened by Greg’s bad-natured gaping. Bruce’s fearsome movement forward is balanced by Brody’s recoil and his comically fixed stare into space.

And sometimes the layering and balancing can take place within the reaction itself. In John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, Mark Lee enters a restaurant and pretends to be playfully feeling up a woman in the corridor. But he’s actually planning to kill a gangland leader, who’s partying in a room off right. First shot: Mark looks winsomely off after the retreating woman. Cut to the leader celebrating.

We might expect that the return to Mark will show his fake expression fade into a sincere one. Instead, Woo simply shows a new expression on Mark’s face as he listens to the party offscreen right.

Eisenstein admired Asian theatre for its “acting without transitions”; here the brief shot of the gangster eliminates the emotional transition taking place on Chow Yun-fat’s face. Mark’s determination is all the more forceful for being so abruptly presented, as if a mask has simply fallen away.

Mirrors like big faces

Prototypically, the reaction shot shows a face expressing emotion. The technique trades on our ability to grasp expressions, often very quickly. We’ve perfected this skill since birth, and there’s evidence that newborns are pre-wired to detect and respond to certain expressions, especially from mom. Exposure to actual expressions in their daily lives allows children to refine and tune this proclivity. So one part of the reaction-shot technique is a very well-practiced skill that cinema has exploited.

Some recent findings in neuroscience suggest that reactions portrayed onscreen can arouse us deeply. Back in 1995, researchers observed that one sort of nerve cell was activated in a macaque monkey’s brain when the monkey reached for a peanut. No surprise there, since that cortical area is known to be a region involved in planning and initiating bodily movements. But researchers noticed that the same cells fired when the macaque watched another monkey reach for a peanut. Soon researchers were finding clusters of these “mirror neurons” in human beings, strongly suggesting that when we see someone do something, our brain responds as if we were doing it ourselves.

Since facial expressions involve stretching and relaxing facial muscles, it’s possible that mirror neurons play a role in arousing empathy. The mere sight of someone smiling or frowning can trigger some of the same neural events as when we smile or frown ourselves. We’ve all experienced a sort of “motor mimicry” when a radiant smile makes us involuntarily smile too. In one set of experiments, neuroscientists found that people’s mirror neurons responded the same way to film shots of disgusted faces as they did to disgusting smells in real life. Reaction shots may gain their strength from not merely our ability to understand facial expressions but the power of facial expressions to trigger in us an echo of the emotion displayed. With a string of shots of smiling faces, as in the Music and Lyrics concert, our own impulse to smile would have to be put down by force of will.

Of course, characters can display their reactions onscreen without being shown in reaction shots in the modern sense. Many films of the earliest years portray the actors in a long-shot framing of the entire action. Realizing that our eyes will turn to areas of high information content like hands and faces, directors often staged and lit the action for easier pickup of the faces. You can see examples of that in this and this earlier entry.

But the reaction shot as such implies cutting, either breaking down the scene through analytical editing or building up a scene from details (so-called constructive editing). In the 1910s, directors began systematically creating a scene from separate shots. (For more on this development, go here and here.) In this approach, particularly as practiced in Hollywood, a person’s facial expression could become part of an ongoing suite of shots, each concentrating on one item of information. Thanks to cutting, the facial reaction could be underscored, sharpened, and timed for best effect. The suddenness of the cuts to reactions in Music and Lyrics and Jaws is central to their effect.

A reaction shot need not be a close-up, and it need not show only one person. One of the funniest reaction shots in cinema, I think, occurs in The Producers, when Brooks cuts from the “Springtime for Hitler” number to the audience’s frozen, slack-jawed response. This long-shot framing suggests that we should think of the reaction shot as a functional category; it’s a role that various types of shots can fulfill.

Still, the development of the close-up as a technique is tied its function of showing responses. In silent cinema the people’s faces, reacting to the flow of story action, are providing a continual measure of the characters’ states of knowledge and feeling. Entire scenes could be played out as a string of intercut reaction shots, as Kuleshov proved in theory and the Americans showed in practice. In Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, as above, the reaction shot is virtually the dominant technique. And point-of-view cutting patterns integrated the isolated close-up reaction shot with images showing what the character was seeing.

With the emergence of sound cinema, you could argue, the reaction shot was briefly demoted. In early talkies, scenes were played in wider shots, and cut-in reactions could, in the hands of inept directors, seem brusque interruptions. But fairly quickly the reaction shot returned, usually as a stressed moment in a scene built out of more distant and neutral framings. Nowadays, with directors using fewer ensemble shots and disinclined to frame actors in prolonged, balanced two-shots, the reaction shot has retained its place in popular moviemaking.

Apart from registering a character’s response, the reaction shot also offers a broader take on the action. Noël Carroll has suggested that the reaction shot can steer us toward the proper way we should construe the whole fictional world we’re witnessing.

For instance, both fantasy fictions and horror stories feature monstrous beings. But in fantasy a troll or griffin might be benevolent. In large part, the way we construe the monster will depend on how the other characters respond. If the hero or heroine looks kindly upon the creature, as in The Golden Compass or Pan’s Labyrinth, then we know we’re not supposed to be horrified. Carroll explains:

A creature like Chewbacca in the space opera Star Wars is just one of the guys, though a creature gotten up in the same wolf outfit, in a film like The Howling, would be regarded with utter revulsion by the human characters.

Reaction shots instruct us in how to respond to the fictional world as a whole.

So robust is the reaction shot that it can stand on its own, if it gets a bit of help from context. In The Third Man, Holly Martins has been trying to defend his old pal Harry Lime from accusations of crooked dealing. When Holly visits a hospital ward, however, he sees what Harry’s bogus penicillin has done to babies. But we don’t; director Carol Reed shows us only Holly’s dispirited reaction.

As Clive James puts it:

The movie’s whole moral structure pivots on that one point. Unless we are convinced that the two men are seeing horrors, there would be no justification for Holly Martins’ delivering the coup de grace to his erstwhile friend.

A chase through feral eyes

Reaction shots can modulate across a scene, as the characters’ feelings change. But I’m also impressed by the way a scene can build emotion by developing from flat, affectless reaction shots to more intense ones. A good example is the long climactic highway chase in Road Warrior.

The outlaw gang is pursuing a tanker truck they think is full of gasoline, while Max, the Feral Kid, and a few warriors ride the monster truck. The scene’s stunts, acrobatics, and vehicular mayhem are impressive, but these qualities have been replicated in a lot of movies. What gives the Road Warrior scene a special pungency are the many reaction shots of the characters mounted on the truck. For the most part we’re aligned with them both physically and emotionally, and we are allowed to share their moment-by-moment reactions to each turn of events.

Early in the sequence, when the tanker team knocks out some pursuers, we get unequivocal reactions of jubilation.

But as the marauding gang gains control of the tanker, the reactions of the team turn to glum, nervously comic dismay.

The scene’s emotional graph is traced most thoroughly in the reactions of the Feral Kid. Throughout most of the film he has two expressions—neutral and fierce. Clinging to the side of the truck, he watches the steady progress of the pursuers with mild apprehension. If he started to shriek with fear now, the scene would have nowhere to build to. I think that we’re inclined to read his expressions as signs of his characteristic stoicism.

But when Max starts to dispatch gang members with his shotgun, the Kid lets out a hoot of pleasure. At one point a thug sends an arrow into the cab. No emotional response from Max or the Kid.

Max blows the thug off the roof of the cab. The kid crows.

The Kid’s laugh licenses us to laugh too—at the businesslike crispness of Max’s response and at the sheer infectiousness of the Kid’s admiration. (Our mirror neurons are presumably working overtime.)

The next phase in the arc comes when Max orders the Kid to crawl out onto the truck hood to retrieve the shells. Now the boy’s expression becomes cautious and a little fearful.

He sprawls on the hood and grabs the shells. At that moment Wez pops up, clinging to the front grille, and we get two lunging reaction shots.

If the Feral Kid had shrieked earlier in the scene, these cuts would have less impact. The high point of the drama is matched by the fact that finally, something has happened to scare the bejesus out of this boy. Even Max has lost his cool, wrenching the wheel ferociously.

Soon, in another laugh-inducing reaction, Wez realizes that he is point man in the crash that is soon to come.

You couldn’t ask for a better example of how reaction shots can be more than a one-off tactic. In Music and Lyrics, the quick insert of Greg gave a little jab to the scene. In Road Warrior, the Feral Kid’s changing reactions add an emotional curve to the progression of the chase. Without him, the scene would lack a whole layer of feeling.

There’s much more to say about the reaction shot. We’d want as well to talk about films that withhold information about characters’ reactions—by using enigmatic or ambiguous reaction shots, or by eliminating reaction shots altogether. (Think Antonioni, Hou, Angelopoulos, Tarr, and others.) Maybe I’ll take those matters up in another entry. For now, let’s salute one of the most enjoyable and arousing dimensions of cinematic storytelling. It only seems simple.

My quotation from Noël Carroll comes from The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 16.

Reflections in a crystal eye

Whew! After many months of work, we finally sent in our revised third edition of Film History: An Introduction. Elsewhere on this site you can read about its earlier incarnations, and we expect to say more about it as it approaches publication in February 2009. But writing this tome isn’t as fast as webposting, for sure.

So how did we celebrate? A meal out and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (after about sixteen trailers for Paramount and DreamWorks releases). As with Beowulf and Ratatouille, we talk/ write about it together, but not in dialogue form. Kristin gets her time at the podium, then David. And there are of course spoilers.

Don’t even mention pyramid power

Kristin here:

I enjoyed the first half or so of IJatKotCS, but gradually it occurred to me that it wasn’t really building. It was violating the basic law of suspense films, which is to make your villain threatening and the things at stake important. Sure, in the B-film serials that inspired the Indiana Jones films, the premises are ludicrous. But so are the sets and the acting and just about everything about them, because they were so cheaply and quickly made.

With Indiana Jones, these adventure films become high-budget productions with the biggest, best special effects that money can buy. They star actors who have won or been nominated for Oscars. Moreover, the scripts don’t imitate the clichéd, bare-bones plots of the Bs. These are complicated stories that not only move ahead at a pace undreamed of in the serial days, but they toss in many little details and in-jokes in the backgrounds. With Steven Spielberg directing, one expects the non-stop thrills to also make sense, at least in a casual way.

Eventually I became distracted by the fact that certain things stopped making sense to me. Most obviously, what is at stake with that crystal skull? The Soviets want it, and Irina Spalko informs Indy that it’s to make a psychic weapon. Hmmm. And what is that, exactly? She doesn’t explain, and it’s clear that the Reds don’t know enough about the crystal skull to really understand what they’d do with it. In fact, they need Indy to help them every step of the way, and after a certain point his expertise becomes irrelevant, and they’re all dependent on Prof. Oxley to lead them to the kingdom.

I suspect most people’s reaction to her “psychic weapon” announcement is to think she’s nuts, deluded. The skull has apparently driven Oxley crazy (John Hurt playing loony as only he can do). Or did that just happen because he was locked in a very grim Peruvian insane asylum? We’re allowed to go on wondering if the skull has any psychic powers until the scene where Indy gets strapped in a chair and forced to stare into the eyes of the skull. The fact that he is so profoundly shaken by the experience finally shows that the object does have some sort of psychic effect.

But how could it be a weapon? Earlier an atomic bomb has gone off, and that’s engineered by our side, the good guys. How could a psychic weapon top that? Are the Russkies going to strap all the American soldiers one by one into chairs and make them stare into the skull? Talk about creeping Communism!

Spalko can’t explain it to us, since she is trying not only to get the skull but to figure out its secrets. Up to the very end, she says “I vunt to know.”

Of course, ignorance on the part of the villains need not be a problem. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis didn’t know what power the Ark of the Covenant contained until it was too late. At least there, though, we understand from early on that the Ark really is dangerous in what is presumed to be a physical way. Moreover, there the villains were Nazis. We know what horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the world, and we and our allies actually went to war with them. With the Soviets, it was largely a long, tense brinksmanship. Luckily we never found out what a war with the USSR would be like. Today, well after the Soviet Union imploded on its own, the paranoia over reds in our midst seems quaint in an adventure film. Early on Indy and his department chair (Jim Broadbent) lose their jobs, and in a glum scene they deplore how Americans’ irrational fear of Communism has caused it. Yet soon after we discover that there really are Communist spies looking to steal America’s secrets. A mixture of tone, to say the least.

In Raiders, the Nazis seemed to be part of a worldwide network of spies. Spalko seems to be operating with only the group of soldiers that accompanies her. She never reports back to “headquarters.” One wonders if maybe Khrushchev sent her off on a wild-goose chase to get rid of her for a while.

Professor Jones Flunks Archaeology 101

One thing that distracted me and that seems to vitiate the notion of real threat in IJatKotCS is the fact that it’s based on hoaxes and wacko theories. At least there’s some archaeological evidence that elements of the Bible have their bases in real events. There may have been some sort of Ark of the Covenant and a Holy Grail. But to base the premise of the film on Chariots of the Gods (Erich von Däniken, 1968) and crystal skulls gives it a certain ludicrous quality that wasn’t there in the earlier films’ premises, wild though they were.

The film flits lightly past the nuts and bolts of how that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came to be. Presumably, as in Chariots of the Gods, the aliens arrived and traveled around giving instructions on how to build such things as pyramids and Easter Island statues. The room in IJatKotCS where artifacts from Egypt, China, and other ancient cultures are gathered implies that long ago the aliens visited the earth, collected examples of the fruits of their teachings, and … instead of putting them in their space ship to take home, they left them in a chamber that would be crushed when the Kingdom built over the space ship is destroyed. (Don’t get me started on where the ancient Peruvian warriors who pop out of the walls to briefly chase the good guys came from.)

Then there are the skulls. The “real” crystal skulls held in museums, most notably the British Museum one referred to in the film, have been shown to be objects made in modern times, probably within the past 150 years. Those skulls, however, are of normal proportions. The ones in the movie are strangely elongated. Head-binding, Indy offhandedly explains.

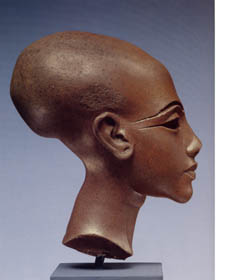

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

In fact, we still have no convincing explanation as to why this style occurred in Amarna statuary. (The Egyptian expedition I work on is at Amarna, the ancient city built by Akhenaten, and I work with statuary fragments found there.) The film, of course, doesn’t bring Akhenaten into it, though I think I did spot a photo of the seated statue of him in the Louvre on the chalkboard of Indy’s classroom. Akhenaten is a figure of considerable interest to New Age enthusiasts. Every now and then a group of people in white robes and turbans actually come to Amarna to worship in the ruins of the temples.

The ancient-aliens-visited-earth premises and the less explicit references to Amarna are woven in with El Dorado and with the Roswell myth that modern aliens visited earth. There’s even a nod to the Alien Autopsy film that David discussed in an entry on “Film Forgery.” The film also brings in the mysterious Nazca Lines, the shapes carved into the earth over which Indy and Mutt fly as they arrive in Peru. Some have claimed that the lines are runways for alien ships, and I think the film tries to imply that. But why would a flying saucer that takes off (and presumably lands) vertically need a runway, let alone one shaped like a monkey or any of the other complex figures that survive today?

The silliness that hovered near the edge of plausibility in the earlier films has crossed that line. At least the first and third movies made an effort to ground their mcguffins in real history and real places. Tanis, where a lengthy portion of Raiders takes place, is a real set of ruins in Egypt. In Last Crusade, Indy and his father can spar by showing off their knowledge of actual or apparently actual history. (I’ll leave it to the comments on the “goofs” page of the Internet Movie Data-base to deal with the transfer of the Mayans from Central America to Peru.) Each of those films was a race to prevent a lethal object falling into the hands of those who would both desecrate it and use it for evil purposes. Crystal Skull is a race to figure out what the apparently dangerous object is, given that the only person who knows, Oxley, is conveniently rendered unable to explain it.

Indy and his group win the race and get to the chamber ringed by crystal skeletons first, so that Spalko is effectively defeated before she gets there, though she doesn’t know that yet. Which brings me to the last thing that baffled me. Why, if the thirteen skeletons were separate beings, as they are depicted in the wall paintings, do they merge into one before being restored to life? Apparently the space ship was waiting to depart because, unlike in E.T., the aliens didn’t want to leave one of their number behind. But is there more than one alien left at the end to depart in the huge ship? Does the ship wait simply because it brought only one passenger, and that passenger can’t start it moving until it gets its head back? Yet surely there would have had to have been a crew to help build all those ancient wonders and bring the evidence back to the “kingdom.”

Maybe a second viewing would clear all this up, but the old serials didn’t need second viewings to be understood—and neither did the earlier Indy films.

The Spielberg Touch

DB here:

Kristin’s critique reminds us that the classic Hollywood structure demands a linear logic, but not a plausible or even particularly deterministic one. Like other action films, Crystal Skull follows the template she pointed out in her New Hollywood book: four parts, the first three running about half an hour and the climax somewhat shorter, the whole capped by an epilogue. It goes to show the difference between plot structure and the events of the fictional world that structure presents. The structure can make preposterous or puzzling chains of action seem acceptable—especially if it whisks them along.

I was taken, as usual, by Spielberg’s brisk direction. In the last decade he’s had a remarkably hot hand. Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, A. I., Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal (much underrated, I think), The War of the Worlds, and Munich are very strong movies. For all their faults (sometimes those slippery endings), they would be enough to establish a younger director at the very top. So I was watching for what I take to be The Spielberg Touch.

His staging is still solid and resourceful. When he has to let people talk, he moves them around the set, avoiding those dreary passages of stand-and-deliver that most directors today resort to. (Check the dialogue scenes from The Matrix Reloaded.) In a soda fountain, he lets your attention drift from the exposition between Mutt and Indiana to the teenyboppers behind them, to the point where I was distracted from Mutt’s explanation of those muddled plot premises Kristin points out.

Spielberg has said that he favors lengthier shots than are typical today. That’s true in most of his dramas and comedies, but here the cutting is fast. The shots average 4.6 seconds by my count, which is about the same as the other Indiana Jones films (1). But whatever his shot length, Spielberg doesn’t resort to choppiness, the sort of image-snatching that typifies today’s mainstream cinema. He’s one of the few filmmakers working today (Shyamalan is another) who tries to give most shots a distinct arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Granted, most shots in any movie will develop or progress, even if a character just steps forward or raises an eyebrow at the end of a spoken line. But Spielberg enriches his shots in the way that the old adage suggests: The only problem of direction is to prepare the audience for what is going to happen next.

The ambitious Spielberg shot starts with something that links precisely to a previous shot, then develops a visual or narrative premise of that, then ends with a firm point of information that carries us into the next shot. His main tools for building the shot are are spatial depth and camera movement.

Linking the shots, in multiple ways

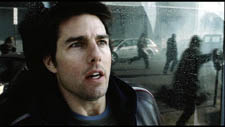

In War of the Worlds. the protagonist Ray is hurrying toward the center of his neighborhood, where people are gathering. He passes a garage, where the mechanic Manny and his assistant are trying to fix a burned-out ignition. As Ray strides by, he suggests changing the solenoid, and Manny agrees. This becomes important later, when Ray will seize the vehicle because it’s the only civilian car that’s working.

Spielberg binds his shots together in this way. The end of the first shot shows Ray, along with others, hurrying to the left. Cut to a shot from inside the garage, with a silhouette in the foreground bending over a car’s engine. Ray becomes visible in the distance.

Ray’s appearance and reappearance link the shots, while Spielberg’s composition has prepared us for a dialogue between Ray and the man, as yet unseen, in the foreground. Cut to a moving point-of-view shot of Manny rising and turning to Ray (us) and explaining what has happened.

Reverse shot of Ray, still trotting along, over Manny’s shoulder as he suggests changing the solenoid. As he goes on, cut: The moving shot now detaches itself from Ray’s point of view and shows Manny ordering his assistant to change the solenoid. The assistant bends over the engine.

Cut to another driver bent over his engine. This reiterates the story point that everybody’s car has stopped, but it also echoes the end of the last shot (and the beginning shot of Manny in silhouette). Crane up slightly to pick up Ray walking leftward in the distance, an echo of the foreground/ background interplay of the Manny/ Ray shot.

How to develop this shot? We follow Ray, along with a skateboarder, to the intersection, where Spielberg introduces a new element. The shot gradually brightens and as Ray moves to the major intersection, rays of light wash out the image.

The next shot will repeat this pattern, from darkness to rays of light, so that the following shot can start with a burst of light that envelops Ray.

Then a new story component, involving Ray’s two buddies, comes in from the foreground. Their conversation with Ray will get a tracking shot devoted to it, but it will end with a story point….and so on.

Spielberg maps his story points quite precisely onto the beginning/ middle/ end of his shots so that they link smoothly with one another. Each camera movement or depth pattern leads to a distinct revelation, sometimes a fresh one, sometimes an expansion or specification of information we’ve already received. This is one reason he uses so many matches on action, even in simple dialogue scenes. The last bit of one shot can serve as the premise for the next if its movement can be carried over the cut.

Something extra between the shots

Sometimes that last bit is a surprise. Something pops up in the foreground or on the frame edge, or the camera slides over or back to reveal something that impels us toward the next shot. In Crystal Skull, Indy swiftly empties a refrigerator, hurls himself in, and as he yanks the door closed it swings toward us revealing the label LEAD LINED before it shuts . . . and the atom bomb goes off.

Sometimes the end-of-shot payoff sets up a motif that itself will be paid off later. When Ray runs from the spindly, towering alien vehicle, he ducks around a corner and halts, but Spielberg’s framing gives us time to see the fleeing crowd reflected in a shop window. Spielberg introduces a new motif when Ray, stepping out from behind a car, is standing near a man taking a photograph.

Shortly, another reflection, this time supplying both action and reaction: the alien walker seen in in a shop window as people inside stare at it. And again we have photography, when, in a shot echoing the earlier one, a man upstages Ray and films the creature’s advance with a video camera.

At the climax of this string of shots, the creature’s approach is again given in reflection, only now it’s Ray standing alongside it (bringing together two elements previously kept apart, Ray and the reflection of the aliens). After the creature sends out its death vibes, the video camera falls into the shot, showing us, in its own version of reflection, the fleeing crowd–the subject of the first reflected image we saw.

Following the end-of-shot hooking principle, the image on the video screen will link to the next shot we see of the people fleeing in panic. My larger point is that the braiding of motifs—reflections, photography—ends with them knotting together in a single image, the shot of the video camera. This sort of patterning was something that Eisenstein both theorized and practiced; he called it “wickerwork” montage construction. Spielberg has, in the context of American action pictures, rediscovered how powerful it can be.

He brings the same shot-by-shot fluency to dialogue scenes. A small scene in The Terminal shows Victor tussling with an official over his passport. Spielberg sets it up with our old friend, over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot, but he gives us two bits of business: The official slipping Victor’s plane ticket into a pouch, and Victor grabbing back his passport.

Match on action as the official continues to put away the ticket and demands the passport. A change of angle to a profile view adds a little amusement to the scene.

In reverse-angle Victor warily extends the passport. Cut back and forth as the two men tug on it, the action accentuated by a squeezing sound.

The official wins, and he slips the passport into the pouch. Spielberg gives us a variant on the reverse-angle on Victor, adding a fast rack-focus that resolves the scene with a neat snap.

In making even small gestures engage us in a visual flow that is rhythmically arresting, Spielberg displays craftsmanship of a high order. Despite his influence on a generation of filmmakers, this level of skill is rare today. If this be Storyboard Cinema, make the most of it.

I’ve already gone on too long, but I want to suggest that this cunning arc of interest, of doling out story points within shots and across cuts, also quickens his chase scenes. We say that his action scenes are clear, and partly that comes from his patient willingness to design long shots and overall views that keep us oriented. But these sequences also draw us in because shot by shot they build carefully, with little transitions—a glance, a gesture, a shift of focus or framing—that crisply link to what we will see next.

I saw a little of this crispness and fluidity in the pursuits of Crystal Skull. They can’t help but seem fairly stale, since Spielberg is competing with himself and with directors who learned from him (e.g., John McTiernan in Die Hard). And as per convention, bad guys have bad aim and they run out of bullets at an awkward moment. Yet the chases still piled complication upon silly complication, from ants and rapiers to cliffs and waterfalls, often set up at the end of one shot and paid off at the beginning of the next, which also sets up another.

The Spielberg Touch includes some visual wit. Everyone remembers the shot from Jurassic Park showing the T-Rex pursuing the Land Rover, as reflected in a side mirror saying “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.” I think the habit goes back to Jaws, possibly still Spielberg’s best movie: the billboard with the graffiti and of course the rise of Bruce from the sea as Brody is scooping chum over the side. To make audiences gasp and laugh at the same time is no mean feat.

Crystal Skull seems to display less of this wit. The glimpse of the Ark of the Covenant in the warehouse and especially the montage of a squeaky-clean suburbia about to be vaporized were typical Spielberg, but I wanted more. Maybe a second viewing will show me that more.

But I was glad to see the Roswell ingredient here, and to learn that Indy did his duty in July 1947, even if he wasn’t there for the alien autopsy.

Faces and light

Finally, a little image-cluster that recurs in Spielberg’s work intrigues me. It was in Close Encounters that I first noticed his fascination with linking faces and beams of light. In that movie people just watch, transfixed by the luminous aerobatics of the vagrant UFOs and then eventually by the four-alarm light show pumped out by the mother ship. Then there’s the iconic image of Elliott staring at E. T.’s luminous digit, and the radiance of the church in the above scene from War of the Worlds.

Light beams can be punishing too. They melt faces in the first Raiders and blow a woman’s face to bits in War of the Worlds. They’re back again here—sprayed out by an alien intelligence and infecting the bad guys. Poor Irina Spalko, played with pelvic-thrust relish by Cate Blanchett, absorbs the rays through her eyes before detonating in one of those Armageddons that are obligatory in today’s megapicture. (Why do blockbusters have to include literal blockbusters?)

Maybe a critic in the vast Spielberg literature has discussed this dynamic between uplifting light and damning light, the enthralled face and the blasted one, characters spellbound by light and doomed by it. My hunch is that it will take us into religious and/or New Age territory.

(1) I get 4.3 seconds for Raiders, 3.5 for Temple of Doom, and 4.7 for Last Crusade.

Minority Report.