Archive for the 'Books' Category

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

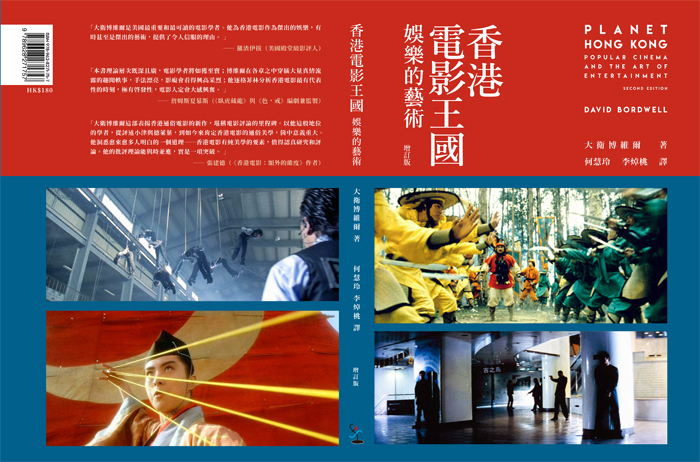

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

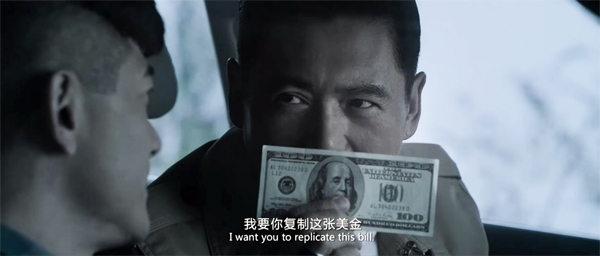

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.

Back on the book beat

Phoenix (Christian Petzold, 2014).

DB here:

One of my undergrad professors told me: “Bordwell, you have to decide whether you’re going to be a reading man or a writing man.” Professors of the male persuasion talked that way then. When I said I wanted to be both, my mentor puffed his pipe. He really smoked a pipe. He said: “It’s damn hard.” This kindly man knew English Renaissance drama and poetry practically by heart but never wrote a book.

I start to see what he means. For some decades, I managed to read a fair lot and write a decent amount. You’d think in retirement it would get easier. But I have too many interests and projects, and publishers dump a heap of intriguing items on the market every week. The months go by, the books pile up on the side table and on the floor, and I try to keep up. I really do. I’m always behind.

So at intervals I stop obsessing about 1910s cinema and 1940s Hollywood and Rex Stout and how best to think about film form and style, and I swerve to what colleagues are discovering. Turns out, quite a bit. What better time than a plague to catch up?

Flooding the zone

What’s it like to live across the street from a prolific polymath?

For twenty-five years we had as neighbor James W. Cortada, a genuine intellectual range rider. Trained as a scholar in Spanish diplomatic history, he finished his Ph.D. in one of the worst hiring years: 1973, the same year I came out. I was lucky to find work, but Jim took a job selling IBM computers. Eventually he became an executive specializing in innovation and management.

But he was also a compulsive researcher and writer. While holding down a desk job and supervising staff and toting PowerPoints around the world, he managed to publish books in a host of areas. He was a guru of Total Quality Management, producing books and yearbooks on the subject. He also became a premiere historian of computer technology, with such classics as Before the Computer. What I like about this book is the way it integrates study of the tools and machines with examination of the office-based practices of sorting, bookkeeping, and other mundane activities. Unbelievably, Jim continued his graduate interest in Spanish political history. Along the way he wrote a research manual (History Hunting), turned out a study of 9/11’s impact on business, and edited with Alfred Chandler a massive book on information in US life.

Jim writes any size. He has produced The Digital Hand, a magisterial trilogy surveying the use of computers in American life. What about the rest of the world? That’s covered in The Digital Flood, another showstopper. Then there’s IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon, which is the definitive account of a corporate behemoth, with access to information only an insider could obtain.

Not to mention (so I’ll mention it), Jim’s more or less single-handed creation of a whole discipline: the history of information. The ideas are there in early works, but the first crystallization was the stupendous All the Facts, a sweeping survey of how Americans passed along data–not just in business but in cookbooks, diaries, maps, and other vessels of knowledge.

Since 1971 Jim has authored or edited over seventy books. Retirement has revealed what a slacker he was before. Between March 2019 and March 2020, he published four volumes. He also found time to head our neighborhood association, contribute many articles to professional journals, play with his grandkids, and banter over burritos at El Pastor (before lockdown).

You haven’t lived until your neighbor drops by at the cocktail hour with the cheerful greeting, “How many words did you write today?” Fortunately, he’s utterly generous. Jim reads everything I show him, immediately giving me helpful advice. He’s just an all-around intellectual who, because of the 70s job market, wound up in a non-academic line of work. He shows what you can do if you have brains, pluck, and a hunger to find things out. Long before our millennial “knowledge workers,” he showed what a rigorous university education could bring to corporate culture.

Probably the most immediately significant items in Jim’s recent output are two books he wrote with William Aspray. From Urban Legends to Political Fact-Checking: Online Scrutiny in America, 1990–2015 is a scrupulous in-depth account of how fake facts and the debunking of same stretch back to the very origins of the Net. The book digs back to pre-Internet online legends circulated on Prodigy and America On Line, chief among them being the infamous Willie Lynch letter purporting to instruct planters how to discipline their slaves. The bulk of the book shows how over twenty-five years, rumors and half-truths become depressingly long-lived.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misrepresentation in America is broader and aimed at a more popular audience. It offers eight historical episodes as case studies in rumor and deceit. The earliest instance is the presidential election of 1828, which blended corruption, sex, and racism in an intoxicating cocktail: “General Jackson’s mother was a COMMON PROSTITUTE. . . . She afterwards married a MULATTO MAN, with whom she had several children, of which member General JACKSON is one!!!” Nice to know triple exclamation points aren’t an invention of tweens and trolls. The book surveys conspiracy theories around the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, mythmaking in the Spanish-American War, and disinformation in controversies about Big Tobacco and climate change. It’s a completely fascinating read.

It’s also fairly dispiriting. It brings out the Mencken in me, admittedly never far from the surface. The books suggest that the venality of hoaxers, the credulity of the multitude, and the social incentives to hide the truth and spread lies don’t promote a public demand for accuracy and nuance. What we see now, in the Republicans’ current attempt at a fascist takeover of our civil society, is the implementation of Steve Bannon’s suggestion to “flood the zone with shit.”

It’s not that the wacko alternatives carry much weight, though they do play to darker desires. More important is the sheer firehose fusillade of preposterous claims. Who can keep up? Nuanced fact-checking seems only to add to the swirl of uncertainty. Are coronavirus cases being undercounted? Overcounted? Confusion and overload are central to the plan. Instead of “Drain the Swamp,” the motto is “Swamp the Drain.”

So books like Jim’s and Mr. Aspray’s buoy us as we paddle to keep our heads above the waves of sludge. Meanwhile, Jim is eight chapters into his next opus.

Techbeat

Jim’s work as a historian of business technology reminds us that tech is a part of film history too. But for many decades, materials, machines, and tools weren’t sufficiently reckoned into the study of film. Scholars of early cinema were, I think, the first to examine the standardization of equipment and film stock; Gordon Hendricks’ dauting Edison Motion Picture Myth (1962) situated the emergence of moving-image technology in the context of Edison’s corporate strategy. Eventually, by the 1980s, people were considering the role of camera and lens design, lighting rigs, film stock, and camera carriages in shaping film style. Our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema was one effort in this direction.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

His analyses of scenes from 1930s and 1940s films, both classic and obscure, train the reader in what to watch for. In all, it’s a persuasive meshing of functional explanations of style with causal accounts of what goes on behind the scenes–not least, the sheer sweat of pushing dollies and following focus. He draws an enlightening contrast with the brain-work of producers, screenwriters, and directors.

The work of production is bodily. The actors move their arms and legs and torsos, and the grip and operator move theirs. Each must anticipate the others’ gestures, like dancers in an ensemble. the Hollywood studio system relied on preproduction planning in order to rationalize production, but the process of filmmaking ultimately came down to craftspeople working together in the moment. One type of collaporation was corporate; the other was corporeal (158).

A graduate of our program, Keating carries forward our respect for filmmaking craft, including its more toilsome routines.

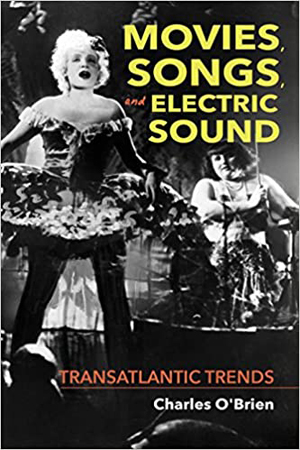

No less sensitive to the concrete demands of technology, and the ingenious workarounds that can be discovered, is Charles O’Brien’s account of the international transition to talkies, Movies, Songs, and Electric Sounds: Translatlantic Trends. Like Keating, he’s studying a body of conventions, here those that arose in the vogue for the international “song film” in 1928-1934. And like Keating, he’s very precise. He measuresg average shot lengths and brings out the implications of how much time is devoted to songs or dialogue.

But this is no simple data dump. O’Brien charts the various strategies in which song sequences allude to the theatre situation and absorb themselves into the ongoing story line. He traces a distinction between the Hollywood song sequences, which were quickly relegated to farces like the Marx Brothers films, and the European sequences, which adapted more varied forms, such as pantomime and verse-like dialogue stretches. The latter strategy was especially common in Germany, partly due to the studios’ commitment to direct sound. O’Brien offers a particularly cogent account of the virtuoso carriage scene in The Congress Dances (1931), which in its joyful excess remains stunning today. (See clip above.)

O’Brien further contextualizes his discoveries by considering broader business culture, such as the market in song recordings and sheet music. All in all, a tight, coherent account of how technological change introduces both functional equivalents of existing techniques and spillover effects–unexpected advantages that artists can exploit.

Shawn VanCour’s Making Radio: Early Radio Production and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture focuses similarly on technology and craft at this period, bringing in other institutional pressures on craft workers making audio artifacts. In fascinating detail, Shawn (another UW alumnus) shows how the separation of body and voice created by radio broadcasts posed many problems for engineers, writers, and other staff. One result was a sort of “practical theory,” a body of ideas about what radio essentially was, alongside particular practices that shaped both technology and dramaturgy.

For instance, everybody recognized the need to dramatize story action with sound effects and music, but paramount was the need to keep dialogue clear. The compromises and trade-offs were debated in trade journals and executed on the airwaves, with fascinating effects on standards of proper audibility. One consequence was the valorization of a “radio voice,” the mellifluous tones suited to the new medium’s demands, both technical and institutional. VanCour shows that these debates were picked up in the motion-picture industry at the period O’Brien investigates. Sometimes, less often than we think, inquiries do converge in fruitful ways.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

This is an encyclopedia that reads like a series of engaging art history lectures. In his opening, Paolo acknowledges the avalanche of new material he faced. More than fifty thousand features and shorts have survived from the years 1894 to 1929, and research has expanded accordingly. He pursues three questions: What was silent cinema thought to be at the time? How may we study it? And why does silent film matter as an expression of culture? These questions are pursued in fifteen chapters bearing one-word titles like “People,” “Building,” “Duplicates.”

No summary can do justice to the world that this book opens up. We learn about the machines, the venues, the processes, and the people. There are floorplans of studios and theatres, comparisons of different color processes (gorgeous), and discussions of how projectionists regulated the speed of the show. The book devotes a whole chapter to theatre acoustics, the use of sound effects and recordings, and even the clapper sticks used by the benshi commentators in Japan. Another fascinating chapter traces the fate of a single film through multiple versions, from camera negative to digital format. Throughout, Méliès’s Trip to the Moon is used as a benchmark to remind us of all the ways that every copy is a unique artifact, a claim that Paolo has advanced consistently over the years.

Silent Cinema is a must-have book for everyone interested in cinema of all eras. Its publication price made it the film-book bargain of the year, but Bloomsbury and Amazon are now offering it on obscenely generous terms. If you’re not a silent fan, this giddy ride can make you one.

Auteurs never went away

The Headless Woman (2008).

At intervals people tell us that we need to stop studying directors and turn instead to Culture or Other Collaborators or some other inputs. Surely the classic formulations of auteur criticism have some problems. Still, it’s terribly hard to shake the idea that a great many films are usefully understood in light of directors’ purposes and plans. Directors play a central role in the production process and under certain circumstances are granted the possibility of building a body of work. We can argue about Roy del Ruth or Michael Bay, but not certain “strong filmmakers” who have, as Andrew Sarris put it long ago, personal visions.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

There’s an extensive body of close analysis on Tati, to which Kristin in particular contributed as far back as the 1970s. Malcolm adds to this with some keen studies of framing, sound, and gag structures. What he brings to the table is the way that distinctively modernist conceptions of humor and comedy find their way into this vaudeville-inspired entertainer. From aleatory gags–apparently random synchronizations of noises and movements–to fragmented and incomplete or unconsummated gags, such as the precarious taffy that doesn’t quite plop off its hook, Tati intuitively reawakens the spirit of irrational laughter that inspired avant-gardists.

Malcolm traces Tati’s lineage back to Albert Jarry, Jean Cocteau, and the avant-garde’s fascination with circus and music hall. Other sources were Chaplin, Léger, and René Clair. In a sort of feedback loop, the avant-garde borrowed from slapstick comedy, while Tati’s cinematic transformation of music-hall numbers into decentered, absurd, or perplexing cinematic sequences revives the anarchic spirit of the modernists. His satire of the postwar managed society sought to make us see the world around us from a potentially subversive angle. The dreary vacation routines of M. Hulot’s Holiday and the opaque surfaces and chilly contours of Mon Oncle and Play Time are disrupted by characters who revel in disruption, and a filmmaker who imagines our daily march easily turned into charmingly clumsy dance. Beneath the paving stones, the beach, went a May ’68 slogan. “His was the quintessentially avant-garde project,” writes Malcolm, “of closing the gulf between art and life” (p. 237).

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

All the more welcome, then, is Brad Prager’s monograph on Phoenix in the Camden House German Film Classics series. This is an admirable close reading of Petzold’s film, bringing a range of cultural references to bear on the suspenseful story of a woman returning from a death camp to a husband who, it turns out, has his own guilty secret.

Prager skilfully invokes the citations–Vertigo, Siodmak’s work, American noir–and considers how Petzold’s genre affiliations (he often makes politically inflected thrillers) merge with his examination of trauma in German history. It isn’t easy to do justice to the film’s remarkable climax, which I decline to spoil for you, but Prager manages it. This scene is one of the great fake-outs in recent film, I think, and Prager is alive to all its bleak ironies, including the heroine’s rendition of Kurt Weill’s “Speak Low.”

Phoenix (the book) is a model of compact, probing analysis. I’d be happy to have Prager tackle another Petzold, especially one I just saw and much admire, his first feature The State I Am In (Die innere Sicherheit, 2000), which seemed to me to do for Fritz Lang what Phoenix does for Hitchcock. More generally, Petzold has a pictorial exactitude we seldom see nowadays, and he deserves wide-ranging study.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

All the features of a classic auteurism were here (and in The Holy Girl, 2004): persistent themes, distinctive plotting, signature style. These qualities are given full consideration in Gerd Gemünden’s Lucrecia Martel. Gerd has done a thorough job in surveying her career and dissecting the films. He shows that she is especially interested in rendering physical sensation–textures, touch–through evocative images and sounds. Anybody who has seen La ciénaga can’t forget the opening scene’s glimpses of a scummy swimming pool and flaccid necks and groins, let alone the wine and splinters of glass splashed onto a drunken woman’s corrugated chest. The rain in The Headless Woman is no less palpable, while the humid torpor of the colonial outpost in Zama is sticky almost beyond endurance. This tactility makes Martel’s stringent criticism of class inequities even more powerful.

This critical aperçu finds its place in Gerd’s comprehensive account of Martel’s oeuvre. As is usual in the series Contemporary Film Directors (yeah, an auteur title for sure), we get detailed production dossiers, wide-ranging background on literary sources and cultural context of reception, and close studies of the films. There’s also a rich bibliography and an interview with some surprises; for such an elliptical, visually oriented director, Martel claims that oral storytelling is a primary inspiration.

Auteur studies are not what they used to be. Instead of paeans to directorial genius, they can be subtle, wide-ranging discussions of what Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent.” Acknowledging influences, circumstantial pressures, forced choices, opportunities, and the like, our writers can show that some directors still build up films that yield resonant personal expression. Choice within constraints: that’s the story of creativity in all the arts, and the most nuanced auteur accounts can show how that process works in fascinating detail.

Will we still have books as the coronavirus burns its way through our lives? Can publishers survive? Yes, we’re sequestered, and maybe that’s encouraging us to read more; but people will have a lot less money for books. What will entice us to invest in personal libraries?

An encouraging sign is that so many of the books on film here have very fine illustrations, many in color. So thanks to the publishers for understanding that well-reproduced pictures can attract readers as well as document arguments. And Silent Cinema includes a filmography with references to online collections. With books like these, we can correct and expand what my old prof said: You can be a reader and a writer and a viewer. Now we just need time, and safety.

Each of these books represents an integral research project, but all are part of larger research programs too. Jim Cortada’s work is an epic instance, but we find the same trajectory in the film scholars’ careers. As writer, archivist, and filmmaker, Paolo Cherchi Usai has devoted his life to silent cinema. Patrick Keating’s study of camera movement joins his first book on the history of Hollywood lighting. Charles O’Brien has already given us a fine-grained comparison of the conversion to talkies in the US and France. Shawn VanCour is active in archiving sound and is exploring radio’s relation to other acoustic media. Malcolm Turvey’s book on Tati joins his earlier books on avant-garde filmmakers’ conceptions of vision and 1920s modernism in Europe. Petzold’s film is a natural step beyond Brad Prager’s work on Herzog and on visuality in German Romanticism. Gerd Gemünden’s many books include one on German exile cinema and Billy Wilder’s American films.

Kristin’s writings on Tati from the late Seventies are in her Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis.

P.S. 29 May: I just got another volume that chimes with this entry. It’s Marco Abel’s The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School from 2013, and it’s a very comprehensive and in-depth consideration of this important group.

Trafic (Jacques Tati, 1971).

Nolan book 2.0: Cerebral blockbusters meet blunt-force cinephilia

You want to go see a film that surprises you in some way. Not for the sake of it, but because the people making the film are really trying to do something they haven’t seen a thousand times before themselves. . . I give a film a lot of credit for trying to do something fresh—even if it doesn’t work.

Christopher Nolan

DB here:

Christopher Nolan has scheduled a new film for summer 2020. That’s all we know at this point. It’s a nifty coincidence that this week we’re releasing the second edition of our little e-book, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. It’s now available for purchase at $3.99.

Kristin and I have rewritten and expanded the 2013 edition to include discussions of Interstellar and Dunkirk. In addition, I’ve taken the opportunity to develop some new arguments about Nolan’s career. In particular, I claim that he has developed a consistent and fairly adventurous “formal project” revolving around the treatment of cinematic time. I also consider his efforts to make what the industry calls “event films” and The Hollywood Reporter calls “cerebral blockbusters.”

My online exploration of those ideas got me into trouble some while back. A well-known critic vehemently criticized my blog entry on Dunkirk while announcing that he refused to read it. His Facebook fulminations taught me a few things about internet culture and film reviewing, and I’ll try to spell some of them out shortly. First, though, let me introduce the new version of our book.

Preview

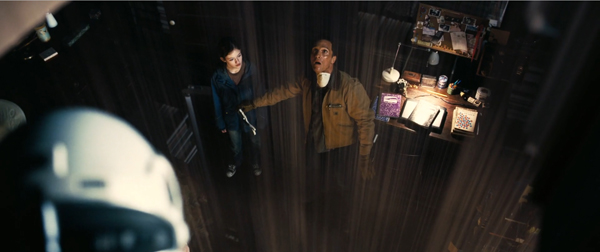

Dunkirk (2017).

The earlier edition was in portrait format and contained embedded video clips. The new version is squeezed into the more grateful landscape format and contains links to online clips. This makes the file less bulky to download. As you’d expect, we’ve added more clips, from The Prestige, Interstellar, and Dunkirk.

The book’s argument has four strands.

(1) Nolan is best understood as working with traditions and trends in contemporary American cinema. Following and Memento blend classic studio conventions (chiefly of film noir) with independent cinema’s tendency toward “complex storytelling” at the end of the 1990s (partly due to Tarantino’s influence). His Dark Knight trilogy aimed to bring serious themes to the emerging comics-superhero model. Our book has little to say about the Batman franchise, except insofar as it encouraged Nolan to try various stand-alone experiments.

A trend toward “intellectual” genre cinema, seen especially in The Matrix (1999), gave Nolan the opportunity to make his “cerebral blockbusters”; the Wachowskis’ film became a model for Inception. Important as well was the impulse toward richly realized story worlds (“worldmaking”) pioneered by Lucas’s Star Wars franchise and carried along in the fantasy and SF genres.

(2) Contemporary American cinema has enabled a few directors to launch “formal projects.” A filmmaker can develop a signature style or method recognizable from film to film. Wes Anderson is perhaps the clearest example in the US, although Hong Sangsoo is a good overseas instance. I argue that Nolan quite self-consciously launched a distinctive formal project in his work, applying it to a variety of subjects and genres. A new chapter develops this idea.

What is this formal project? I’d say it consists of experiments with cinematic time by means of techniques of subjective viewpoint and crosscutting. From Following to Dunkirk, Nolan has explored various ways of manipulating story time and the viewer’s experience of it. I devote a new chapter to spelling out the idea, taking seriously his emerging idea of a “rule set.” The rule set not only governs the film’s construction but becomes a guidance device that spectators must learn to understand the story.

After using Following and Memento to illustrate Nolan’s overall project, the book devotes later chapters to showing how rule sets shape The Prestige’s dual-protagonist plot, Inception’s nested-dream device, Interstellar’s time-travel agenda, and Dunkirk’s three levels of story duration. In the course of these chapters, I try to show how Nolan addresses criticisms that his work is emotionally cold (one chapter is called “Pathos and the Puzzle Box”) and how he has managed to develop his project in the framework of genres and studio “event pictures.” The biggest challenge is clarity: keeping the audience up to speed with story action when plotting and narration are fulfilling the sometimes arcane rules.

(3) The first edition of our book began by acknowledging that Nolan’s work divides audiences. Many film viewers like his films, some consider them masterpieces, and others consider them worthless. Here’s the new book’s opening, slightly modified from the first edition.

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other American directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

As of fall 2018, his films have earned over $4.7 billion at the global box office, and at least as much from cable television, DVD, and other ancillary platforms. On IMDB’s list of the top 250 movies, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) currently ranks number 4 with nearly two million votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned over 1.7 million. Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Peter Jackson each have three films in the poll’s top 50. Nolan is the only director to have five.

Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s blockbusters and his more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006). From Following (1998) onward, his films have won between 76% and 94% “fresh” ratings on the aggregating website Rotten Tomatoes. Even Insomnia (2002), probably his least-discussed film, earned 92% “fresh.” Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet some critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. People who shrug off patchy plots and continuity errors in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The vehemence of the attack is probably in part a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

More on the critical controversy below. At this point, it’s enough to say that our book argues that Nolan’s formal project illuminates certain capacities of cinema. He shows us some new things that cinema can do.

Innovation, then, is another strand in the argument. We pick up on Nolan’s suggestion that all other things being equal, innovation is worthwhile. (“I give a film a lot of credit for trying to do something fresh….”) Our opening chapter (“How to Innovate”), retained from the first edition, continues:

I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear. I have some reservations about them too. Yet I think that all parties will agree that Nolan seeks to be an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and originality in popular cinema.

After decades of trying to trace the bounds of novelty in popular cinema, I think that Nolan’s work shows that the conventions of popular cinema are intriguingly flexible. As in the silent era (see many of our entries, especially those on the 1910s), as in the 1940s (see Reinventing Hollywood), as in the 1990s (see The Way Hollywood Tells It)—today’s American cinema can accommodate intriguing experiments in storytelling. There are limits, of course, but they aren’t as rigid or strict as some think.

Put more theoretically, the capacity of classical storytelling to exhibit “trended change” allows classical principles to be instantiated in various unforeseeable ways. This entry explains the argument a bit more.

4) Where does this leave the critics who despise Nolan’s work? The book argues that critics should be more open to the cinematic implications of the movies they encounter. They shouldn’t consider a film they may dislike merely as something to be dismissed or another nail in a despised director’s coffin or an occasion for displays of writerly cleverness. (The recent victim is Serenity. Maybe the umbrage is deserved, but it makes me want to take a look.)

Critics concentrating on evaluation can miss how even films they don’t consider good or likable can shed light on the possibilities of cinema. As our introduction puts it:

Taking this stance suggests that it can be useful to look at the artistic history of films apart from our urge to rate goodness and badness.

Once again, I find myself agreeing with Nolan’s remark quoted at the top of this entry. Even though something fails, it can be worth trying if it opens up some creative possibilities. Critics could signal these, if they chose.

These four ideas, along with detailed analyses of Nolan’s films, form the substance of the book. You can buy a copy on our order page, which contains more information and a table of contents.

The follies of Facebook

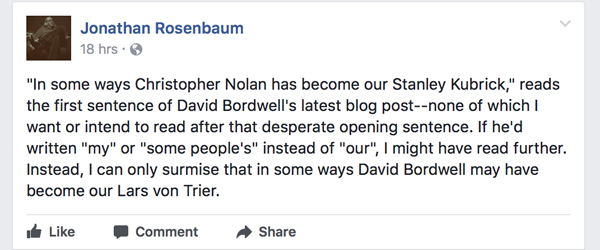

After the internet, nothing seems weird. Still, the August 2017 email from an overseas friend took me by surprise. It was headed “Re: Rosenbaum” and began: “What a turd!” before continuing in a similar vein.

Jonathan Rosenbaum has my permission to stop reading this now.

I don’t do Facebook or any other social media myself, so I had no idea what my friend was referring to. Using Kristin’s account, I learned that on a Facebook page JR had posted the remark you see above in response to my blog entry on Dunkirk. (That entry has developed into a chapter in our book.)

I was mostly bemused by the Facebookery. Actually, I didn’t understand it.

I didn’t understand the reference to Lars von Trier, whom JR has praised many times.

I didn’t understand what was desperate about my effort to grasp Nolan’s latest release as part of a larger trend toward event films as “personal” projects, typified in earlier times by Kubrick’s work.

I didn’t understand the objection to my use of “our,” which the entry clearly indicates as referring to mainstream US film culture today.

I didn’t understand how I could stagger someone by comparing two notable filmmakers. Nothing I said in what followed suggested I was comparing them on grounds of quality. Indeed, had JR checked our blog or read our book, he’d learn that I’ve written about both flaws and strengths of Nolan’s work.

Above all, I couldn’t understand why someone would refuse to read further, and then proudly tell his Facebook Friends™ he did it. This seems curiously close-minded, especially when six minutes of Googling dredges up many passages in which JR castigates critics for refusing to see movies they comment on.

Wolcott’s deepest scorn was reserved for those “sullen Village Voice reviewers” who “praise movies so obscure that simply getting to the theater counts as a quest for the authentic.” One of them, he pointed out, had the nerve to write hyperbolically about a recent Godard video — something that Wolcott presumably couldn’t be bothered to see himself.

“[Godard’s] most recent films,” I concluded, “are simultaneously investigations into and lessons about how to see, hear and understand our everyday existence. Regardless of how one ultimately judges them, it is irresponsible to call them frivolous; far more frivolous is the critical intelligence which refuses to grapple with them.”

I saw as well that some of his Friends™, who also had not read the piece, had joined the chorus. Still, Facebook isn’t exactly an arena of Ciceronian subtlety. So I shrugged. Why not let JR and his Friends™ blow off steam?

But a few of his Friends™ bothered to read my piece and pointed out that his reaction misunderstood my points. And some who hadn’t read the piece began treating my first sentence as an essay question in Contemporary Movies 101 by speculating on what evidence might warrant it. Indeed, some of his readers arrived at claims akin to mine.

JR responded by escalating. He had to go and compare me, on obscure grounds to Trump–a figure I’ve castigated on more than one occasion. To this I demanded an apology.

JR replied on Facebook with an excuse masquerading as an apology. As I’d predicted, he shifted the grounds of the original objection. Turns out it was my fault: he claims that my first sentence misled him because it was so poorly written. (Sorry to report, it remains in the Nolan book.) The whole thing–starting silly, turning a bit nasty, and ending with the critic scuttling off trailing a cloud of muttered gripes–exemplified yet again the superficiality that Facebook encourages.

My email correspondent might call it a close encounter of the turd kind. Still, I think I learned things. I began to think again about how criticism that depends heavily on evaluation can lead to a dogmatism about taste and a close-mindedness that blocks intellectual inquiry.

Call it blunt-force cinephilia.

A brief guide to militant cinephilia

Petulia (1968).

In an earlier entry, I argued that critics do lots of things with language. They describe artworks; they analyze them; they interpret them; and they evaluate them. Typically, academic critics concentrate on description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation usually takes the back seat.

By contrast, journalistic critics, aka reviewers, heavily weight evaluation. After minimally describing the film, they offer consumer recommendations. They guide us to recent releases that they favor and steer us away from ones they don’t. But evaluation, I claimed, can appeal to two standards: more or less objective criteria of judgment and more or less subjective tastes. The reviewer may appeal to criteria that readers share (a thriller shouldn’t have plot holes, a comedy should induce laughter), or to tastes.

Tastes are subjective, but they’re also shared with others. I like even somewhat cheesy kung-fu films, and maybe you do too. I’m not prepared to call them excellent on objective criteria, but they give me pleasure. A reviewer often signals a film’s taste dimension with “If you like this sort of thing, you’ll probably like this new film.”

But some reviewers, as they acquire knowledge of films and film history and film culture, build up a cluster of distinctive tastes. And some reviewers become well-known, and they gather followers. Soon the critic’s preferences and hatreds become part of the critic’s public identity, and the followers align their tastes, to one degree or another, with the critic’s.

And when a critic becomes a celebrity, he or she may be tempted to make tastes part of the brand, to minimize judgment based on criteria and exaggerate the importance of tastes. And to whale away on films aimed at alien tastes.

One branding option, popularized I think by Pauline Kael, was a sort of weaponized evaluation. Bad films weren’t simply slipshod or shallow, but they were outrages, profound insults to cinema and humanity. “Is there any art in this obscenely self-important movie?” Kael asked of Petulia.

Militant cinephilia of this sort offers all sorts of rhetorical advantages. It paints the possessor as a pure guardian of what’s valuable. It allows the critic to write wildly, spraying bullets at many targets, so it has a jittery readability. It encourages hatchet-wielding, since most films won’t measure up. Demolition jobs, like Godzilla movies, are fun.

Dogmatic cinephilia also favors the narcissistic personality who disdains dialogue or common pursuit of ideas. And it glamorizes the critic’s brand. Who would want to be sane, reasonable Stanley Kauffmann if you can cheer Kael wrestling with the demons of commerce? This is how cults of personality grow.

Militant cinephilia rests largely on the critic’s taste arsenal. Deployed carefully, it can yield good results–stimulating conversation, pointing out faults and beauties in films. But cinephilia turns dogmatic when the tastes keep you from considering evidence or alternative arguments. Ironically, the dogmatic cinephile winds up limiting cinephilia, and cinema itself.

As a sketch, I’d offer this list of symptoms of blunt-force cinephilia.

You see it or you don’t. The critic makes sweeping claims, usually in the form of piled-up adjectives, without much evidence.

Differ if you dare. The critic simply negates any opposing views by attributing disagreement to base motives or a blinkered assimilation to dominant tastes. You cashed in, sold out, unthinkingly accepted what you were told.

Fondness for the sideswipe. If dogmatic cinephiles were forced to justify their claims in some detail , they might nuance them. But reviews, like Facebook postings and tweets, have to be brief. (No time or space to go deep.) They favor short, sharp bursts of dislike, zingers, what in another context Matt Taibbi calls “anger chiclets.” The same scattershot approach can be found in longer pieces as well, where a celebrity critic can pile up strings of pans or panegyrics.

My cinephilia can lick your cinephilia. When you overstate (or “overreact,” as JR puts it in his Facebook apology), as you inevitably will, it’s because you just love cinema so much. Your passion is so volcanic that of course sometimes it will burst the bounds of reason. Never say “It’s only a movie!” Movies matter tremendously! See how much I care? My vehemence is righteous, and I smite the sinful.

The mutation of militant cinephilia into dogma brings us back to JR’s outbursts. If you’re a critic defining yourself largely by tastes, my fairly bland sentence about Dunkirk can look like an armed provocation. Dogmatic cinephilia can operate on a hair-trigger.

More basically, I suspect that JR doesn’t welcome film criticism that suspends or just ignores evaluation. But I think it’s not only possible but desirable to hold evaluation in check if we want to know how films work and work on us.

The writing we do on this blog and in our publications is of course fueled by love–of the medium, of filmmakers, and of films. Evaluation mostly enters as a choice of what to talk about. We tend to write about films we think are good by some criteria. Usually, we like them as well. Sometimes we try to convince you to rank them high and come to like them.

Still, many of our points should hold good independent of evaluation. Often we try to see films as affording glimpses into cinema’s artistic practices (conventions, strategies) and, when we encounter novelty, its fresh possibilities. This is at bottom the premise of the Nolan book.

Both journalistic reviewers and high-end critics often lack curiosity. They don’t seem to think that films can teach them anything about cinema they don’t already know. We, like Nolan in our opening quotation, want to be surprised by something, even if it doesn’t quite come off. At the limit, we try to learn things about cinema from films that others, or even we ourselves, might not like. That’s another valid way, we think, of being a cinephile.

For more on our Nolan book, see this entry.

An older blog entry considers other games cinephiles play.

Besides the Nolan book, what would criticism that plays down evaluation look like? Many of our blog entries and books try to hold judgment and tastes in abeyance in order to answer research questions about form and style. See, for an example of a film that has ardent supporters and skeptics, our entries (here and here) on La La Land. For a wider effort to compare several films without emphasizing value judgments, try my roundups of narrative strategies in releases of 2015 and 2017. Then there are the older essays on Mission: Impossible III and staging in 1910s Nordisk films. For more extended examples see the book Poetics of Cinema.

Interstellar (2014).