Archive for the 'Actors' Category

Mark Rylance, man of mystery

Kristin here:

I asked Rylance, a most certain Best Supporting Actor nominee, if success would spoil him now. He had a good retort: “I thought I was successful already!” Indeed, he sure is. But Hollywood will embrace him.

Will it? Well, it can try. It should try.

SPOILERS for Bridge of Spies ahead.

Another great veteran actor who came out of “nowhere”

Upon reading the reviews of Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies published over the past few weeks, many American moviegoers may have been puzzled by the fact that one of the most highly praised elements of the film was the supporting performance of Mark Rylance. Indeed, the praise was often unusually enthusiastic, with Rylance already considered a favorite for a supporting actor Oscar nomination or even win. I suspect that the vast majority of Americans have never heard of Mark Rylance, three-time Tony winner, two-time Olivier-award winner, Emmy nominee, etc. He fits the cliché of the “overnight success” who has been around for a long time and was, as he says, “successful already.”

In Bridge of Spies, Tom Hanks plays the lead, real-life lawyer James Donovan. In the late 1950s, Donovan accepted the unpopular job of defending a Russian spy, Rudolph Abel (played by Rylance), when he came to trial. Later he agreed to negotiate with the Soviet government to swap Abel for downed American pilot and spy Francis Gary Powers. Bridge of Spies is not one of Spielberg’s most exciting or endearing films, but it’s very well made and as classical in its traits as a film can be. It sits nicely beside his other historical dramas, Lincoln and the excellent Munich. On the whole the film has been well-reviewed, with a 92% favorable rating from all critics on Rotten Tomatoes, increasing to 98% among top critics. Rylance is clearly a major reason for the excitement.

It’s Rylance who keeps Bridge of Spies standing. He gives a teeny, witty, fabulously non-emotive performance, every line musical and slightly ironic — the irony being his forthright refusal to deceive in a world founded on lies. (David Edelstein)

Because this is Hanks we’re dealing with, audiences know what to expect, though the revelation here is Rylance (an actor Spielberg also cast as his forthcoming BFG), who appears utterly transformed — to the few who recognize his typically charismatic screen presence — into a balding, Eeyore-like gray moth of a man. (Peter Debruge; the reference is to Spielberg’s The BFG, with Rylance in the lead as the Big Friendly Giant, based on the Roald Dahl children’s novel and now in post-production)

Rylance, one of the greatest of contemporary stage actors, has to date had only an intermittent screen career, but Bridge of Spies suggests that could be about to change. He brings fascination and very, very subtle comic touches to a man who has made every effort to appear as bland, even invisible, as possible. (Todd McCarthy)

Brilliantly played by British theater legend Mark Rylance — who nearly steals the show. (Lou Lumenick)

Meanwhile, Rylance, who’s still probably best known for his brilliant work on stage, is the film’s real breakout discovery. With his musical Northern English accent and bemused, ironic demeanor, he turns a story that could feel as musty as a yellowed stack of old newspapers snap to exuberant life. (Chris Nashawaty)

Mark Rylance, the great English actor, director, and playwright who for a decade was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe theater, performs some mysterious act of alchemy in his role as the ineffable and unflappable Soviet spy. Almost without speaking a word, he communicates this character’s rich inner life, in which a near-Buddhist resignation to the whims of fate alternates with a feisty instinct for self-preservation. (Dana Stevens)

Part of the reason why the Germany sequences sag is that they don’t feature Abel, who is played by British actor Mark Rylance in what, with luck, will be a career-making performance. Many viewers may not have heard of Rylance, who recently played Thomas Cromwell in “Wolf Hall” on PBS. But his work in “Bridge of Spies” deserves to be widely recognized as an example of screen acting at its most subtle, poignant and exquisitely calibrated. (Ann Hornaday, who, like Friedman, does not acknowledge that Rylance already had made quite a career for himself)

I could go on, but for more see the reviews by Manohla Dargis, Richard Roeper, Kenneth Turan, and Michael Phillips.

I don’t, in fact, think that the German sequences sag. Basically the first half of the film covers the trial and sentencing of Abel, with brief scenes of Powers’ training for his spying missions flying over Soviet territory. Once Powers is shot down, Donovan goes to East Berlin for the negotiations, leaving Abel behind in prison.

The German sequences involve a marvelously authentic post-war East Berlin, designed by Adam Stockhausen, who won an Oscar for the production design of The Grand Budapest Hotel. (I wasn’t there in the early 1960s, of course, but I did visit East Berlin in 1992, when part of the wall was still up and the place had a very Soviet look, complete with giant busts of Marx and Engels.)

No, these scenes don’t sag, but there is definitely a niggling question in the back of one’s mind: When are we going to see Abel again? Rylance somehow makes this very ordinary-looking, quiet man the heart of some of the film’s best scenes.

Treading the boards

As Rylance pointed out in the quotation at the top of this entry, he already had an illustrious career going long before Wolf Hall and Bridge of Spies hit American screens. (The Wikipedia entry on Rylance  gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

Rylance also won awards playing a variety of very different characters. In 1993 he won his first Olivier award (the top British acting honor) for playing Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing, and followed that up with a British Academy Television award for the TV film The Government Inspector (directed by Peter Kominsky, who later directed him in Wolf Hall, for which he was nominated for an Emmy). He did a comic star turn in a 2007 staging of Boeing-Boeing and was nominated for another Olivier; he won his first Tony when the production moved to Broadway. His second Olivier and second Tony came for his performance as Johnny Byron in Jerusalem, first in London and then on Broadway.

Perhaps Rylance’s greatest success, however, came with a pair of Shakespeare plays done in repertory, Twelfth Night, in which he played Olivia, and Richard III, with him in the title role. Rylance had played Olivia at the Globe in 2002, but from November, 2012 to February, 2013, both plays ran in alternation in the West End. Later they transferred to Broadway, where Rylance was nominated for a Tony as best actor as Richard III and won for best featured actor as Olivia. The plays were done as authentically as possible, with men playing all the roles and wearing costumes true to Shakespeare’s era.

Ben Brantley conveys some of the excitement of these productions and Rylance’s performances in his New York Times review:

In this imported production from Shakespeare’s Globe of London, deception is a source of radiant illumination for the audience, while the bewilderment of the characters onstage floods us with pure, tickling joy. I can’t remember being so ridiculously happy for the entirety of a Shakespeare performance since — let me think — August 2002.

That was the last time I saw the Globe’s “Twelfth Night” (in London), directed by Tim Carroll and starring the astonishing Mark Rylance, in a bar-raising performance as the Countess Olivia. And how thrilled I am that our wandering paths have crossed once more, rather like those of the separated twins at the play’s center.

This “Twelfth Night” — which opened on Sunday in repertory with a vibrant and shivery “Richard III” that allows Mr. Rylance to show he’s as brilliant in trousers as he is in a dress — makes you think, “This is how Shakespeare was meant to be done.”

Walter Kaiser makes similar remarks in The New York Review of Books (available to subscribers only; in print in the February 6, 2014 issue):

The production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night by the English theatrical company Shakespeare’s Globe, currently at the Belasco Theatre, brings this play to life in a way I have only very rarely seen equaled in a Shakespearean production. The performances are so uniformly skillful, the interpretation of the play so intelligent and imaginative, and the costumes and stage set so accurate and evocative that the entire experience is exhilarating. Audiences at the performances I’ve attended have been overcome with delight, clearly somewhat surprised by the affecting immediacy of the theatrical experience they have undergone, unaccustomed to a Shakespeare so readily comprehensible and so vividly alive. You may, if you’re lucky, see another Shakespearean production that’s as good as this one, but it’s unlikely you will ever see one that’s better. […]

Mark Rylance, who over the past decade or so has made the part his own, is undoubtedly one of the greatest Olivias of all time. Frequently, this part is played with a grave, graceful maturity that tends to mask, or at least minimize, the intensity of the emotional quandary Olivia finds herself in when, not wishing to receive any further expressions of love from Orsino, she discovers that she has fallen in love with the messenger who delivers them. Rylance, instead, beautifully exposes her perfervid confusion: overcome with emotion, he stammers (in confirmation of Viola’s observation that “she did speak in starts”), acts with impetuosity, and manifests, at times, an engaging exasperation with his inability to control his passion. His hands alone, in the informative subtlety of their gestures, betray the emotions Olivia wishes to conceal.

I was lucky enough to encounter this Twelfth Night, as well as Richard III, in late 2012 when I was in London for a few days. I’m partial to authentic performance styles in theatre and music, so the chance to see two Shakespeare productions with all-male casts was appealing. Little did I realize that I would be seeing two brilliant turns by an actor I had never seen before–or so I thought. In fact, he plays Ferdinand in Prospero’s Books, but nobody, especially in such a small, bland role, can get much attention when playing alongside John Gielgud as Prospero.

Spielberg discovered Rylance in the same way that I did. In a very informative article based on interviews with Rylance and Spielberg, Jack Cole reveals:

Spielberg was urged to see Rylance in “Twelfth Night” by Daniel Day-Lewis. He calls him “a shape-shifter, a man of a thousand faces and voices who can play any part.”

“Seldom has an actor been around for so many distinguished years on the stage and yet had not been fully discovered for the screen,” said Spielberg by email. “Mark understands that the camera records stillness better than in any other media. His transition from the stage to ‘Bridge of Spies’ was graceful and invisible.”

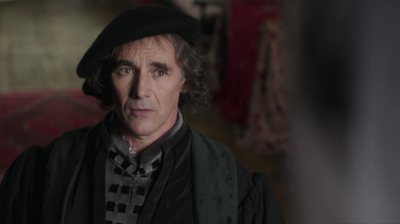

Cromwell and Abel and beyond

Those members of the American public who did know Rylance before Bridge of Spies had probably encountered him as Thomas Cromwell in the BBC series Wolf Hall, a Tudor-era costume drama which aired in six parts on PBS starting April 6, 2015. (David and I streamed it more recently, mainly to see Rylance.) It seems unfortunate that the two breakout roles that have brought the actor to such prominence this year both involve notably restrained performances.

Anthony Lane compared these performances in his New Yorker review of Bridge of Spies:

So what’s it all about? It’s not about the U-2 missions, and certainly not about Powers, who comes across as a lunk. Nor, despite the set pieces in court, is it about the majesty of the law. No, the core of this movie is a standoff every bit as keyed up, and as gripping, as anything on the muffled streets of Berlin. What we thrill to is Rylance versus Hanks: the British actor, lauded for his stage appearances, but barely known to cinema audiences, up against the consummate Hollywood pro. You can see them prowling, probing, and wondering what the next move will be—or, in Hanks’s case, wondering whether Rylance will move at all. Admirers of “Wolf Hall,” on PBS, will have noted him as Thomas Cromwell, standing like a statue in the shadows, and realized, to their discomfort, that they could not look away. He does the same thing here, as Abel; we watch him watching everybody else, as if life were an infinity of spies. “You don’t seem alarmed,” Donovan says when they first meet, and Abel replies with a gentle question: “Would it help?” The Coens turn that into a refrain that beats through the movie, growing wryer and funnier each time—right up to the fidgety finale, where Abel is the calmest man in sight.

Of course, Cromwell does move in Wolf Hall. He moves a lot. Few television series can have shown their protagonists walking from place to place so often and at such length. Rylance modeled his gait on that of a Hollywood star, according to the Cole piece cited above: “He’s explaining how Mitchum, whom he adores, inspired his steady, rigid gait in the international hit series ‘Wolf Hall.'”

More Rylance on Mitchum, from another interview:

I’ve watched lots of films preparing for this, and I was particularly struck by one of my favourite actors, Robert Mitchum, how his performances haven’t dated in the way that even perhaps more versatile actors, Brando and Dean and people of that era, have. I noticed how well he listens, how still he is, how present he seems. You’re drawn towards the screen – wondering what’s he thinking, what’s he going to do next. That’s always the best way to tell a story.

Kominsky describes adjusting his filming style for Wolf Hall to catch Rylance’s subtleties:

The one thing you might not be expecting is that he’s the most minute of film performers. Nothing is overblown. Nothing is writ too large. It’s very, very simple, very understated, his performance, and then you look into his eyes, and it’s all happening. Everything is going on in there, and of course, you’re drawn into closer and closer shots, just to try and capture the emotion that’s going on very slight below the surface, and that’s what I loved to film. (From George Pollen documentary, Sky’s Arts program, 19:00-19:47)

As David has pointed out, however, the eyes as such are not always particularly expressive. It’s the area of the face that contains the eyes that does the job. The eyebrows and forehead usually give the context that tells us what the eyes are expressing.

If we concentrate on the upper half of Rylance’s face, the considerable differences between his Cromwell and his Abel become apparent.

As Abel, he consistently does something rather remarkable: he raises his eyebrows, creating furrows in his forehead, without widening his eyes. That’s not an easy thing to do. The result is a perpetually curious or surprised expression, a sort of mask that Abel wears to suggest that he is naive, innocent, a little slow. In fact, as we discover whenever he speaks with Donovan, he’s well aware of everything going on around him and has considerable insight into it. But it’s the naivete that allows him to dupe the agents who search his hotel room into letting him clean the paint off his palette, thus allowing him to conceal a key bit of evidence.

The key moment during which Rylance drops this tactic happens during his “standing man” anecdote, about a man he knew who survived a severe beating by Soviet agents by simply getting up again each time he was struck to the ground; Donovan reminds him of that man, he says.

As Cromwell, Rylance’s main tactic using his face is to glance away at nothing in the course of a scene where he is conversing with someone or observing interactions among other characters. So much classical editing depends on our understanding of whom or what a character is looking at, but not here. In one scene, Ann Boleyn shows him a drawing she has found hidden in her bed, depicting her decapitated. She asks him to find out who put it there.

Apart from his eyes, Rylance remains uttlerly motionless through the shot in which she holds the drawing out to him. Initially he is looking at her face (that’s the side of her head out of focus in the foreground) and then glances down at the drawing as she holds it up from below the frame.

He then glances down briefly to a point just outside frame right–clearly not at Boleyn’s face or anything else relevant to the action.

He looks at her face again and finally at the drawing.

Nothing here betrays Cromwell’s emotions, since he is a man who has to keep his thoughts hidden from most of the people at court. But that extra shifting of the eyes momentarily to an inconsequential space shows us that he’s thinking. Maybe he has an idea as to who would have left the letter. Maybe he’s thinking of Ann’s sister’s warning to him in an earlier scene, telling him not to help Ann. We don’t know here, as we don’t in many other scenes where Rylance uses this same sort of eye movement.

Both Abel and Cromwell need to conceal their thoughts, but Abel does so through deception and Cromwell through concealment, both conveyed by subtle acting.

In the Pollen documentary, Rylance describes how he avoids putting too much into a performance (in this case referring to lecturing on stage acting to students):

If I was only allowed three words, I could distill all my complicated notes, and you can see how wordy I get if I get talking, to three words, which would be “You are enough.” What’s happening to you is you don’t feel you’re enough, and you’re putting more effort into it than you should. You’ll be in the center of yourself, your voice will be centered, your movements will be centered, and the audience will also believe you more, because they’ll also believe that you’re enough. (8:35-9:08)

In Bridge of Spies, the little gestures and bits of business that Rylance uses to draw our attention to Abel are minimal. He wipes his nose occasionally, apparently the victim of a persistent cold or allergy.

As Michael Phillips points out in his review, this cold creates a parallel to Donovan, who has his overcoat stolen in East Berlin and soon develops a cold of his own:

It’s brilliant, really. What’s the quickest way to establish the humanity of two leading characters in a Cold War drama? Give them both the sniffles. […]

Because he’s relatively new to multiplex audiences, Mark Rylance will likely walk off with the acting honors for “Bridge of Spies.” He looks nothing like the real Abel, but in a largely nonverbal, supremely poker-faced performance — even his stuffy nose is subtle — Rylance suggests a forlorn practitioner of deception who recognizes a lucky break when he sees it.

(Agent Hoffman has also caught a cold by the epilogue; an occupational hazard, apparently, and a subtle comic motif.)

There are other gestures: lengthy tapping of a cigarette on an ashtray and little sucking movements of the lips, suggesting ill-fitting dentures. (A bit more subtle scene-stealing than that practiced by Steve McQueen in The Magnificent Seven, as described by David.)

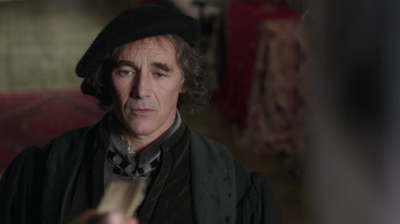

Yet Rylance is perfectly capable of comic, broad performances as well. His Olivier-and-Tony-winning turn in Jerusalem was as a raucous, drunken rascal.

He made Richard III a grotesquely deceitful clown.

His Olivia, though more restrained, can do a broad comic take, as when she first notices Malvolio sporting the detested cross-gartered yellow stockings (see bottom).

We can assume that his acting as the BFG will be miles away from his performance in Bridge of Spies.

Will Hollywood be able to embrace him?

Roger Friedman claims that Hollywood wants Rylance. Possibly, but Rylance is ambivalent about filmmaking and generally prefers the stage. Indeed, I wish I had a reason to be in London right now, since he is back in the theater, receiving more rave reviews as the depressed King Philippe in a limited run of Farinelli and the King, the much-praised first play by Rylance’s wife, Claire van Kampen.

The Cole piece sums up Rylance’s on-and-off relationship to film acting, which involves Rylance being willing to embrace it rather than it embracing him:

For Rylance, embracing movie acting has been a circuitous journey. As a young actor, he watched as his theater contemporaries — Daniel Day-Lewis, Gary Oldman, Kenneth Branagh — became famous on the big screen. Agents urged Rylance into TV and film so that he would be “a complete actor.”

“I just, time and again, was attracted by the theater where I was offered better opportunities,” says Rylance. “I auditioned for films and didn’t get them. I think I had some stuff to learn about film acting. I don’t think I was personally really ready for it. But I did come to resent it. I did eventually think: Why, why? You wouldn’t tell the great Tamasaburo or Ganjiro-san it’s not enough to be a Kabuki actor, you need to be a film actor.”

He rattles off some film experiences he’s enjoyed: the Quay brothers’ “Institute Benjamenta,” a A.S. Bryatt adaptation “Angels and Insects” and a handful of British TV films, like “The Government Inspector.”

“But I’ve made some bad films, too, that have not been enjoyable,” Rylance said on a recent New York afternoon on a day off from starring in van Kampen’s “Farinelli and the King” in London. “At a certain point after one of them I did a few years back, I said, ‘That’s it. I’m not interested in this anymore.’

“I thought: I need to be happy with who I am, where I am. That can be the kind of miners’ dust of being an actor,” he says. “For an actor, being dissatisfied with who you are can be the reason for becoming an actor, but it can become an illness.”

But once Rylance let go of being a movie star, film directors started calling.

“As I did that, wonderful film things started being offered to me,” he says. “Maybe that was partly the problem — that I was giving it too much forced value. Because I grew up in America, so I grew up with some theater. But mostly I saw three films a weekend in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”

Yes, Rylance was a Wisconsin boy, in a sense. He was born in Kent in 1960, and his parents, both English teachers, moved to Connecticut in 1962 and then to Milwaukee in 1969. There his father taught at the University School of Milwaukee, where Rylance first studied acting. “He starred in most of the school’s plays,” as the Wikipedia entry cited above puts it. Returning to England, he studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts from 1978 to 1980. His time in the States suggests why his accent is not quite the normal English one that we expect from the great British actors. It is nice to think that Rylance was avidly attending films in Milwaukee during the same period when David and I were doing the same here in Madison.

Clips of some of Rylance’s stage roles are included in the George Pollen documentary linked above; others can be found by searching on YouTube. Fortunately the wondrous Twelfth Night was recorded and is available on DVD (here in the US and here in the UK). The rest of the cast is excellent, particularly Steven Fry as Malvolio and Paul Chahidi as Maria. The many cameras used in the filming capture the most salient action at every point and alternate details and long shots to give a sense of where the action is occurring. As the image below shows, it was filmed in the Globe, with the audience right up against the stage and quite obvious (in a good way) in many of the camera setups. In the scene below, a spectator gives a wolf-whistle as Malvolio struts about his his yellow stockings, which strikes me as a very groundling sort of thing to do. Having seen the performance from the front-row center of the balcony, I am glad to have a closer perspective.

[December 2: Rylance has won the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[January 3, 2016: Rylance has won the National Society of Film Critics award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 15, 2016: Rylance has won the British Academy Film Award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 28, 2016: Rylance has won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The story linked to here considered this an upset, as Sylvester Stallone had been widely predicted to win. But as I’ve shown here, a lot of us back in October knew better.]

[February 29, 2016: Rylance has been nominated for an Olivier Award for Farinelli and the King.]

[March 6, 2016: Pete Hammond of Deadline Hollywood has pointed out that Rylance won his Oscar without ever having participated in a single campaign event in the awards season. (He was given a day off from his current stage show in Brooklyn, Nice Fish, to go to Los Angeles to attend the Oscars ceremony.)]

[December 31, 2016: The Queen’s New Year’s Honours for 2017 include a knighthood for Rylance.]

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

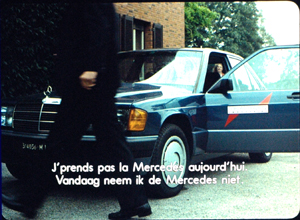

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

Criss Cross (1949).

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

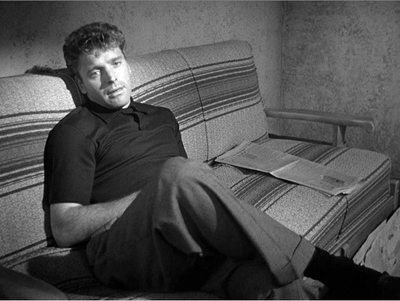

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.

Harry Potter and the Twelve-Year Boyhood

Kristin here–

Note: As far as I’m concerned, Boyhood and the “Harry Potter” films have been out long enough that there is no need for spoiler alerts. It would certainly help in understanding this entry if the reader had some knowledge of the Potterverse.

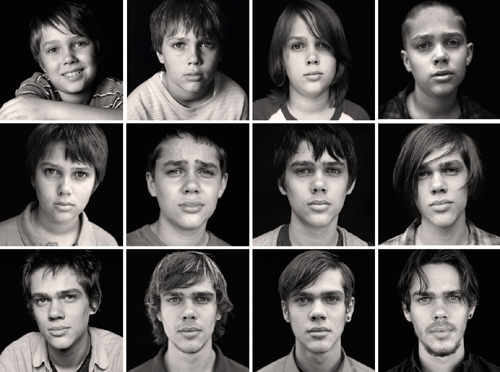

Apparently audiences who saw Boyhood in its premiere screening at Sundance in January, 2014, went in not knowing that the film had been shot at intervals across over twelve years. Once the reviews appeared, it became known that Richard Linklater had done so, recording the actors, most notably Mason, the boy at the center of the film, actually growing older over the course of nearly three hours. The result was an outpouring of enthusiasm from critics and art-film afficionados alike. Less so, perhaps, from more mainstream viewers who went to see Boyhood once the Oscar buzz heated up. (On Rotten Tomatoes, it is rated 98% favorable by critics and 83% by fans.) From its July release up to the recent Oscars ceremony, it was considered one of the front-runners.

The film’s Oscar campaign took a rather puzzling turn toward the end. The film, which was considered unique in its intimate portrayal of one boy growing up in an unstable family situation, was suddenly “Everyone’s Story,” as if it was so universal that we all could see ourselves in it. The double-page spread from the February 20 Hollywood Reporter (which shows photos from each year of shooting) is too large to reproduce here, but here’s the upper section of the right-hand page:

Virtually nothing in Boyhood‘s story reminded me of anything in my life from six to 18, though, yes, I did graduate from high school and go off to college. Maybe men who as children faced their parents’ divorces, physical abuse, frequent moves to new homes, and so on, would relate to the film and enjoy it more than I did. Or maybe less. I don’t think that seeing this as a universal portrayal of the human condition is very realistic, though that was an idea touted by many critics as well.

I was entertained until the last hour or so, when I realized that Mason was going to remaining fairly passive and sullen to the end. His sister Sam and mother Olivia seemed to be more interesting characters, since they had goals, held strong opinions (right or wrong), made mistakes, accomplished things, and so on.

As an actor, Ellar Coltrane spends much of his time listening to what other actors say to him. His reactions are limited in range and usually involve a fairly neutral expression. In fact, I began to think that his performance is the perfect illustration of Kuleshov’s most famous, though lost, experiment: the one where supposedly the same footage of actor Ivan Mosjoukine looking offscreen was cut together with shots of things like bread, a dead woman, a child playing–things that would logically invoke widely varying emotions. Audiences supposedly praised Mozhoukin’s performance, saying he expressed hunger, sorrow, and happiness admirably. Accounts of what was shown in the shots Mosjoukine was “looking at” vary, and it’s possible the experiment was planned but never made. Whatever was the case, however, the principle seems plausible. What we find in a shot, including a shot of a face, depends on what shots precede and follow it.

I think something of the sort happened in Boyhood. Some expert professional actors, plus Lorelei Linklater as Sam, enacted scenes with Coltrane. Spectators may have imagined how a child would react to the events of the scene and read those appropriate emotions in his frequently impassive face. Otherwise it seems odd that people watching a fairly good art film offering a close, realistic study of a family over a period of twelve years, would consider Boyhood such a moving and historically momentous film.

Putting aside the “Everyone’s Story” appeal, Linklater’s film offers the unique case of a feature film shot across the actual twelve years covered by its story, allowing the actors, most dramatically the young ones, to age before our eyes. That’s impressive in itself, with the producer/director/writer Linklater managing to sustain the momentum of the financing and the actors’ cooperation across the full twelve years. I don’t wish to take anything away from that accomplishment, just to put it in perspective a little.

Wait, did I miss something?

As David has pointed out, films that are innovative, even experimental in some ways often compensate by drawing more heavily upon conventions from other areas. Although the jumps from year to year are somewhat disorienting, Linklater helps us out. He draws upon the old device of having the haircuts of the characters differ each time, even emphasizing this way of marking the passage of time by showing Mason getting an unwanted buzz-cut onscreen. He also characterizes Mason in fairly standard shorthand ways. At the opening he seemingly contemplates death by staring at a dead bird that he is burying. His characterization as slightly rebellious is pretty conventional: looking at semi-clad models in a catalog, allowing himself to be goaded into spray-painting graffiti, flirting with a waitress when he should be clearing tables while working at a local restaurant. Apart from the innovative device of the actor growing across a single film, he’s not a particularly original character.

I think, however, that Linklater does something much more interesting with Boyhood, and it has to do with the narrative structure rather than the aging of the actors. The film tells a deliberately sketchy story. Each one-year segment is obviously part of the characters’ lives, but there is little attempt to bridge the gap between them to create a conventional narrative flow. There are no dialogue hooks to create smooth transitions, no overt continuing goals, just Mason’s implicit desire to make sense of life and Olivia’s to find a happy path forward for her family.

Most obviously, events that would ordinarily be explained or motivated are simply ignored. The cuts from one segment to another are sometimes jarring, sometimes subtle enough that we don’t immediately realize that we’re jumped forward another year. As reviewer Kurt Brokaw points out, there are “no turning calendar pages, no inter-titles signaling the passage of time.”

What happens to Olivia’s third husband? (I’m assuming here that Mason Sr. was her first husband.) We see him before the marriage at a party, and he seems a decent enough sort. In a later segment he is married to Olivia. We see little of him, apart from one evening when his sits on the porch drinking beer and berating Mason for coming home late. Will he turn into another drunken abuser, like the second husband? Instead, he just disappears. Possibly in real life the actor playing him dropped out, in which case it would have been easy enough to mention his death or departure–at least something that would motivate his being gone. We don’t, however, get such an explanation.

Similarly, we are concerned when Olivia flees the home of the second, truly abusive husband, taking Sam and Mason but leaving their two step-siblings behind. Sam is upset and begs to take them along, but Olivia is concerned only to escape with her own children. Do the two kids left behind bear the brunt of their father’s wrath? Do they continue to be abused by him or do they somehow break free? These are important questions, especially after the extended and tension-filled scene in which the drunken man threatens Olivia and all four children. In a conventional narrative they would most likely be answered in some fashion.

Another plot point that I wondered about was the sudden introduction of religion into the narrative when Mason Sr., who has shown no signs of religious inclinations, remarries into a profoundly Christian family. Does Mason Sr. become a believer himself, or does he just avoid strife by attending church with her and her parents?

These and other questions occurred to me and were left unanswered. This is clearly not sloppy storytelling but a systematic strategy. Linklater forces us at each leap forward to struggle a bit to figure out where in these characters’ lives we are now–where they’re living, who is still part of their story and who has departed.

Indeed, I’ve never seen a film that compresses time in such a way as vividly to suggest how many people come and go in our lives, some to reappear, some not. I recently was contacted by a first cousin once removed whom I lost track of when my family moved from the Midwest in 1963. Retired, he was sitting in on a film class that assigned Film Art and decided to find out if one of the authors might be his cousin. Turned out he was living in Milwaukee and I in Madison for decades without knowing it. These things happen, and they do seem as abrupt and surprising as in Linklater’s film. That I can identify with.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a narrative film made within or at least on the fringes of the American production system with such frequent gaps and where so many links in the chain of cause and effects are missing. That, in my opinion, is the true innovation of Boyhood, but it’s not something the publicists can sell to the public and the Academy voters.

Right before your eyes

When I heard about the most famous aspect of Boyhood, I immediately thought, “I’ve seen that happen in the ‘Harry Potter’ films.” I was far from the first to think that. An early–perhaps the first–link between the Boy and the Boy Who Lived came as part of the publicity campaign for the film. From July 4 to 10, 2014, the IFC Center in New York ran all eight Potter films in a row as part of a series “honoring the release of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood.” IFC, of course, financed the film and released it in the US on July 11, 2014. Brilliant! as Harry would say.

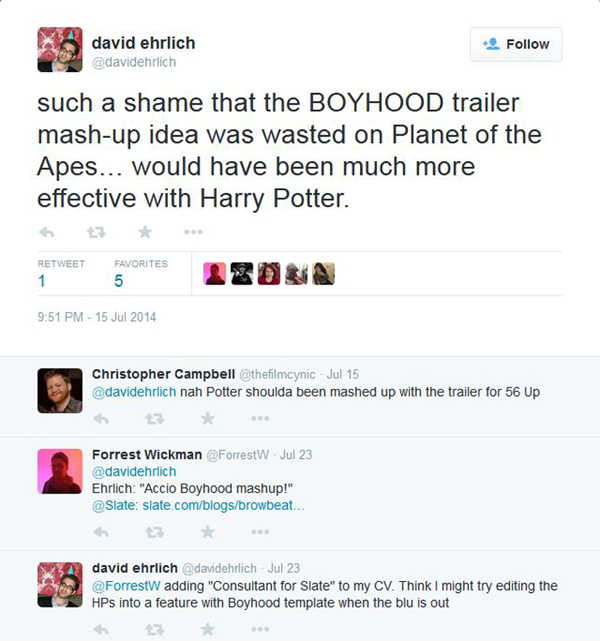

The professional and amateur fans on the internet then took over. On July 15 David Ehrlich (a freelance critic and among other things, Time Out NY‘s associate film editor) suggested a Boyhood/Potter mashup.

You cannot suggest such a mashup on the internet and not have someone take up the challenge. On July 23, Chris Wade posted Potterhood on Slate‘s culture blog, Browbeat, linked in the second comment above. (“Acciao” is a charm for summoning something.) Hence Ehrlich’s last comment in the thread above. A second mashup, also entitled Potterhood, appeared on IGN on February 6, 2015. Hard on its heels was the Honest Trailer – Boyhood, by Screen Junkies, posted on YouTube on February 10, which makes passing reference to Harry Potter. A sequence of five consecutive titles and shots:

The “Harry Potter” series (or, strictly speaking, serial) is only the most recent and well-known example. There have been other “growing-up” series and even a growing-up-and-growing-old series, which Christopher Campbell refers to in the first comment on Ehrlich’s tweet.

Justin Chang pointed out one precedent: “If the ‘Before’ movies are essentially Linklater’s riff on Rohmer, each one an endearingly loquacious two-hander played out against an idyllic Old World setting, then ‘Boyhood’ is unmistakably his tribute to Truffaut, who directed perhaps the greatest movie ever made about restless youth, ‘The 400 Blows.’ Similarly, the French master’s extended collaboration with actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel feels like an early template for what Linklater and Coltrane have pulled off here.”

There are wheels within wheels here. The Doinel series was mentioned to Daniel Radcliffe during an interview, and he responded, “The only one I’ve seen is The 400 Blows. Funny enough, I was asked to see that by Alfonso Cuarón, when he directed the third Harry Potter film. As a reference for Harry and his angst.”

Truffaut’s Doinel series went for a full twenty years, though not with yearly installments: The 400 Blows (1959), Antoine and Colette (1962, a short included in the anthology film Love at Twenty), Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed & Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Unlike the “Harry Potter” series, these films were not planned ahead of time as a group. Truffaut would occasionally pop them in between his other films. They came out after some of his best films–Stolen Kisses after The Bride Wore Black, Bed & Board after The Wild Child, and Love on the Run after The Green Room. At the time we thought of them as Truffaut taking a break after a more difficult project. None of them lived up to the original, but we certainly did watch Jean-Pierre Léaud grow up.

Other critics have mentioned what has come to be called the “Up” series, which began as a television program, Seven Up! (1964) directed by Paul Almond. It consisted of interviews with 14 seven-year-olds. Michael Apted has continued the series with another film every seven years beginning with 7 Plus Seven (1970) and continuing, with the most recent being 56 Up (2012). One participant dropped out permanently, three skipped some episodes, but 56 Up interviewed 13 of the original 14, a remarkable achievement in showing the aging processes across 48 years and still going. Some people have found watching the series a profound experience. Roger Ebert wrote two four-star reviews of it, one in 1998 and another in January, 2013, a few months before his death. He called it “an inspired, even noble, use of the film medium.” But this series is documentary and perhaps not entirely a fair comparison. It is worth noting, though, that Jonathan Sehring, whose IFC had previously produced Waking Life, said that when Linklater pitched Boyhood to him, “The only thing I could draw as a parallel was Seven Up!”

I also wonder if back in the 1930s and 1940s some viewers found it moving as well as amusing to watch Mickey Rooney grow up in the Andy Hardy series, from A Family Affair (1937) to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), plus a revival, Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958), for a total of twenty films. This series was not intended as such at the beginning, but once the popularity of the character was apparent, MGM’s B unit cranked out two or three films a year and clearly planned to keep going indefinitely. These films had self-contained stories, but the subject matter was age-appropriate as Rooney, who was 17 at the time the first film was released, grew older.

Again, all this is not to denigrate Linklater’s film. It’s just a case of this blog seeking again to point out that almost nothing comes out of the blue with no historical precedents or conventions informing it. Certainly none of these series tried the sort of broken chain of causality that Linklater devised.

The Potter connection

Of all the series mentioned above, “Harry Potter” is most pertinent to Boyhood. Their production periods overlapped considerably, and their directors faced similar major challenges. This despite the disparity in their finances. “Harry Potter” had a huge budget supplied by Warner Bros., ranging from the lowest at $100 million for Chamber of Secrets to the highest at $250 million for Half-Blood Prince. (These are the budgets as publicly acknowledged, taken from Box-Office Mojo, which has no figures for the last two films.) Boyhood had a lean budget of $200 thousand for each of the twelve years and totaling about $4 million with postproduction and other expenses added in. Still, as we shall see, the challenges really had nothing to do with the budgets.

I didn’t see Boyhood until the day after the Oscar ceremony, when it was still playing in our local second-run house. I was surprised to discover that it includes references to “Harry Potter,” though to the books, not the films. These are among the several pop-culture and historical references (the Obama-Biden lawn-sign scene, various popular songs) that cue us as to which year of the twelve we have reached.

Early on Olivia reads a passage from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets to Mason and Sam. We don’t see the cover of the book, but it’s a passage that clearly identifies which entry in the series it is. Chamber of Secrets came out in the USA on June 2, 1999. (Incredible as it now seems, the American releases of the first two books were roughly a year behind the British ones and didn’t reach a simultaneous release date until Goblet of Fire in 2000.) The kids are obviously fans, since later they wear costumes to attend the book-store release of Half-Blood Prince, which dates the scene precisely as July 16, 2005. I don’t think the use of Rowling’s series is a random choice. The first six books cover six years in the educations of Harry and his friends at Hogwarts, with the seventh and final one following their attempts to thwart the villainous Voldemort. All begin in the summer, often specifically including Harry’s July birthday. The first six end as the school year concludes, and at the climax of the seventh, Harry, Hermione, and Ron return to Hogwarts for Voldemort’s defeat.

Both Linklater’s feature and the “Harry Potter” film serial face the challenge of retaining the child actors across a lengthy period of shooting. Moreover, neither Linklater nor the “Harry Potter” filmmaking team started with a complete script. The script for Boyhood was written year by year, with input from the actors. The early “Harry Potter” films were made before Rowling had completed her books, and she seldom shared information about what would happen in the upcoming ones.

The boyhood of the Boy Who Lived

Much has been made of the fact that Linklater managed to keep Coltrane committed to the project to the end. Had he decided not to go on playing Mason, the project would presumably have ended. No one connected with the film has ever suggested that the film could have been finished. There was no option of forcing him to commit at the beginning to the full twelve years of shooting, since California law forbids film contracts lasting longer than seven calendar years. (The “De Havilland” law from the 1940s was based on a lawsuit by Olivia de Havilland that changed the Hollywood contract system forever, a story quite interesting in itself.) Given that constraint, however, the production signed Coltrane for the initial seven years and then gave him a second contract for five years. Legally there was one point at which he could have bailed, but presumably the filmmakers would not have forced him to stay with the project if he had badly wanted to stop.

Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, played the supporting but important character of Sam. While Coltrane never wanted to quit, she at one point did, and Harry Potter was involved. The director revealed this last month in an interview in The Telegraph:

Ironically, it wasn’t Coltrane who rebelled against this extraordinary commitment, but Linklater’s own daughter Lorelei. Three years into shooting Boyhood, when she was coming up to 12, she asked her father, ‘Can my character die?’ ‘She wanted out,’ Linklater says now. ‘But that was just one year.’

He learnt the true story behind Lorelei’s rebellion only last month when they were in England, and visited the Harry Potter sets at the Warner Bros studio tour. In one scene in Boyhood, Mason and Sam dress up as their favourite Potter characters and go along to a midnight sale of the latest Harry book. ‘I had Lorelei dress as Professor McGonagall, though I think she wanted to be Hermione,’ Linklater recalls. ‘Those stories were so real in her life. She thought she was going to get a letter from Hogwarts saying she could go there. She thought she might date Harry Potter. Not Daniel Radcliffe, Harry. So I think us filming that scene felt to her that we were belittling that, invading her space. She couldn’t admit it then. But she can now.’ He shrugs, ‘It was a daughter-dad thing,’ he says. ‘Not actress and director.’

Given Linklater’s daughter’s intense involvement in the Harry Potter universe, one wonders if the idea for Boyhood was, at least unwittingly, inspired by Rowling’s creation. By the time the deal for support and casting of Boyhood was settled in 2002, four of the books and the first film had come out. Not that it’s important to my points here, but it’s intriguing. If true, then certainly Linklater took his own project in a completely different direction.

Obviously Linklater persuaded Lorelei to continue, which is all to the good of the film. Mason has a lot of troubles, and having his sister die probably would seem too great a bid for sympathy by the filmmakers.

On the other hand, the “Harry Potter” producers faced the real possibility of having to replace some of the child actors, given that a highly expensive and popular series could hardly shut down because, say, Daniel Radcliffe or Emma Watson decided to leave or came to look too old for his or her role. Certainly there are so many students at Hogwarts that the minor parts could have been recast without difficulty. At minimum, though, it was important to keep the central and the important supporting roles constant: Harry, Hermione, Ron, Fred and George, Ginny, Neville, Luna, and Draco. Obviously keeping the actors in the adult roles constant was desirable as well, though the one replacement that proved necessary didn’t scuttle the series.

Warner Bros., though prescient about approaching Rowling for the rights early on, had little evidence that the first book would be as successful in the US as it had been in the UK. In 2011, Rowling wrote an informative article about her relationship with the series’ main screenwriter, Steve Kloves, who penned all the scripts except for that of Order of the Phoenix. She describes her first meeting with him, just before going into lunch with a big studio executive. (This would have to have been in the period from late summer of 1997 to early autumn, 1998.) She mentions being wary about being introduced to Kloves.

He was going to butcher my baby. He was an established screenwriter, which was just plain intimidating. He was also American, and we were meeting shortly after a review of the first Potter book in (I think) the New Yorker, which had stated that it was unlikely the British idiom would translate to an American audience. You have to remember that my first Warner Bros. meeting did not take place against a backdrop of massive American success for the novels. Although the books were already very popular in the U.K., it was still early days in the U.S., and I therefore had no real means of backing up my opinion that American fans of the book would rather not have Hagrid “translated” for the big screen, for instance.

Odd though it seems now, the “Harry Potter” actors were initially contracted only for the first film. By number three, Prisoner of Azkaban, there was already talk of a change of the young central actors. Radcliffe remarked in an interview, when asked if he thought at the start that he would do all seven movies, “I was never sure I was going to do any of the films, other than signing on for the first and second. After that, it was always going to be: We’ll take it one film at a time.” This suggests that the contracts were made film by film throughout, and that Linklater had a better chance of retaining his main actors than the “Harry Potter” producers did.

There was in fact considerable talk during the production of the “Harry Potter” series that one or more of the child actors would be departing. (The quotations with dates in brackets below are from the imdb news pages for Daniel Radcliffe , which is a handy chronology of information concerning the film series, often excerpted from sites behind paywalls.)

[5 Sep 2002] Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe has resigned himself to growing out of the child wizard movie role–literally. The 13-year-old actor has finished filming the second installment of the adaptation of J. R. Rowling’s massively successful seven strong children’s book series, but his voice has already broken and he’s just had a growth spurt. He says, ‘In a couple of years, I might have changed so much that I look wrong for the part–even though Harry grows with the books.”

[22 Oct 2002] Another company of young actors is expected to take over the principal roles in the Harry Potter film franchise beginning in 2004 for the fourth movie, Chris Columbus, the director of the first two Potter movies, predicted Tuesday. Noting that the current stars, Danial Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint will all be teenagers next year, Columbus told Reuters. “If I were a betting man, I’d say they’ll probably stop after three.”

Indeed, the delays with the third film had allowed the cast to grow more than between the first and second, and the difference is quite obvious in Prisoner of Azkaban (above).

The producers perhaps realized by this point that, although the first two films had been released one year apart (Nov 2001 and Nov 2002), the pace could not be maintained. Indeed, the final film was released in July of 2011. This meant that although seven years of plot duration had passed for Harry and his friends, it took ten years for the films to come out. In most cases there was a one-and-a-half to two-year gap between releases, which came in November or June/July.

The following year there was renewed speculation, this time that the main children would be replaced for the fifth film:

[18 June 2003] Although analysts have suggested that the three young stars of the Harry Potter movies are quickly outgrowing their characters, the Reuter News Agency on Tuesday, citing an industry source familiar with the matter, reported that they will likely return for the fourth Potter film, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, due to be released in November 2005. By that time, Daniel Radcliffe, who portrays Harry Potter, will be 16 years old. Reuters quoted Seth Siegel, founder of The Beanstalk licensing and marketing consultancy group, as warning that if the stars are not replaced by younger actors, “licensing will fade away.” Wendi Green, an agent for child actors with Abrams Artists Agency, told the wire service, “If [they] are too old, kids can’t relate to it.”

Tom Felton, who played the young villain Draco Malfoy throughout the series, said in a 2011 interview that “We all feared that after the fourth film that they were going to get rid of us and start again with new kids. So yes, we’re very proud to have made it through.”

The rumors about the departure of Radcliffe or others continued fairly late into the series: