DB here:

In my early teens I bought murder mysteries from the legendary Claude Held [2] of Buffalo. Lacking a checking account, I blithely sent through the mail dollar bills and even coins taped to the order. I still have S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen hardbacks from those days, but my most treasured item is a first edition of Howard Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story [3] (Appleton-Century, 1941).

Published on the hundredth anniversary of Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Haycraft’s survey of mystery fiction sought to establish the legitimacy of the genre. It became the authoritative source on the subject, and it’s still worth reading. Even then I had the habit of writing notes in the margins, and I’m ashamed of the jejeune scrawls that dare to call Haycraft to account. (“This is quite incorrect.”) Still, Haycraft confirmed my love of the subject and showed me what a serious literary history might look like. (Once more the adolescent window [4].)

Thirty years later came another powerful overview of the genre’s history. Julian Symons’ Bloody Murder [5] aka Mortal Consequences (Harper & Row, 1972) was a revision and partial rejection of the standard story. Haycraft was a critic, but Symons, who reviewed mystery fiction, was also an accomplished novelist. The book is often harsh in its critical judgments, as when Symons downgrades Sayers as “pompous and boring” and classifies many of her peers as Humdrums. Symons promoted instead what he considered the strongest contemporary trend, the shift from puzzles to character-driven and socially critical writing. His subtitle sums up his argument: “From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel.”

[6]Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

[6]Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

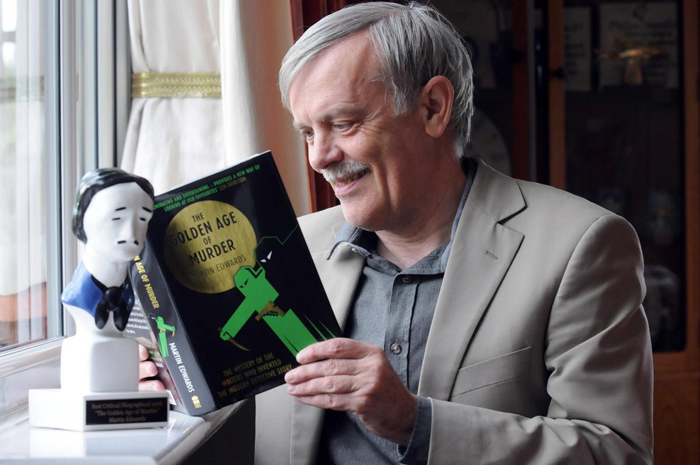

Martin Edwards’ Wikipedia entry [7] makes your head swim: the man is a true polymath. Trained in the law and still a consulting solicitor, he’s a prolific, highly lauded mystery novelist as well. He has won virtually every literary prize in the field, not least the Diamond Dagger, the British Crime Writer’s Association highest award. His most recent novel, published on 1 September, is The Blackstone Fell [8].

Edwards is also recognized as the premiere historian of the genre in English, thanks to his many books, including The Golden Age of Murder [9] (2016) and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books [10] (2017). As if all this didn’t keep him busy enough, he writes a lively blog, “Do You Write Under Your Own Name? [11]And he’s incapable of composing a graceless sentence.

So it’s no surprise that The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators is a monumental achievement. At 724 pages, resplendent with a burgandy string bookmark and beautiful colored end papers, it’s a triumph of modern publishing, and a stupendous bargain. (It’s currently going for $26.39 from the publisher [12].) The hardcover is currently ranked as #1 in Amazon’s Mystery and Detective Literary Criticism [13] (with the audible book as #2).

The bulk and detail of The Life of Crime will incline many to treat it as a reference book. It functions superbly as that, thanks to a careful index, but it is even more. It provides a nuanced, reliable history of the genre; it offers rich insights into storytelling technique; and it teems with unforgettable stories of mystery authors. As the subtitle promises, it’s an account of both books and the people who create them.

Crime waves

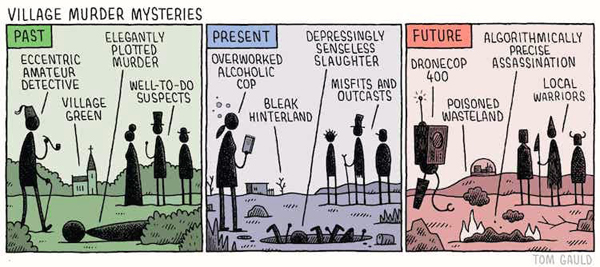

By Tom Gauld [15].

At the end of the 1930s, Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure could confidently sum up the standard trajectory. The detective story developed from Poe to Gaboriau to Conan Doyle, and then to the Golden Age of Christie, Sayers, Carr, Van Dine, Queen, and many others. Haycraft acknowledges the accomplishments of the 1920s British school, their US counterparts, and the emerging hardboiled trend typified by Dashiell Hammett. (Chandler was still a secondary figure when Haycraft was writing.)

Following the most self-conscious writers of the 1930s, Haycraft recognizes the need for the mystery to move closer to prestige fiction. He suggests it do so through a greater emphasis on characterization and on social commentary: the “novel of character” and the “novel of manners.” He sees the hardboiled trend as a variant of the novel of manners and warns that in its pure form it will soon wane. It “is beginning to become just a little tedious from too much repetition of its rather limited themes.”

Time would prove him wrong. The 1940s saw new variations in the hardboiled school, most evident in the spectacular popularity of Mickey Spillane. In Bloody Murder Symons faulted Haycraft’s analysis on other grounds. He failed to discern the growing power of the “crime story” as distinct from the detective tale. Thanks largely to Hammett, violence, eroticism, abnormal psychology, and official corruption moved to the center of writers’ concerns.

For Symons the apparatus of footprints, altered wills, and bodies in the library was surpassed by the rise of suspense fiction and the police procedural. Patricia Highsmith, Symons declared, is “the most important crime novelist at present in practice.” She, along with Margaret Millar, John Bingham, and Symons himself (!) typified the potential of the modern crime story, with Ross Macdonald revising the classic detective plot through the concern for “personal identity and the investigation of the past.”

Edwards holds Symons in high regard but has a more pluralistic conception of the genre’s history. The Life of Crime reaches back to the eighteenth century (William Godwin’s Caleb Williams) and ends with surveys of Nordic noir, East Asian detection, the contributions of contemporary women and minority writers, and the fashion for historical mysteries. The 55 chapters are organized around periods, trends, and exemplary figures. They survey not only crime literature, but plays, films, and television shows.

The broad picture Edwards paints shows how changes in the genre coincide with broader social dynamics. He’s especially good on the impact of World War I on an entire generation of writers and readers. Likewise, he traces how World War II spurred the rise of psychological thrillers in fiction and film, as well as the new platform of paperback originals.

Edwards’ comparative approach shows that the clash of Golden Age and hardboiled tendencies isn’t as drastic as Symons suggested. Symons saw Hammett and Chandler as in rebellion against the “rules” of the classic whodunit. Edwards shows that the hardboiled writers respected not only many Golden Age authors but also many of their conventions. For Edwards, the mystery tradition offers writers a range of creative choices not limited to a single notion of form or style.

An unabashed fan of Christie, Sayers, and their peers, Edwards is especially good at tracing the continuing influence of the Golden Age on contemporary work around the world. Who would have predicted the obsession of contemporary Japanese novelists with impossible crimes and narrative tricks, stemming from the canonical Edogawa Ranpo’s love of classic artifice? Popular examples are Shimada Soji’s Tokyo Zodiac Murders [16](1981) and Higashino Keigo’s The Devotion of Suspect X ( [17]2006). Edwards introduced me to a remarkable “book” by Awasaka Tsumao, The Living and the Dead, which, thanks to the Golden Age trick of sealed pages, contains a short story that disappears as you read the novel. The author, not coincidentally, is a magician [18].

One of the most striking assets of the book is the endnotes at the end of each chapter. Far from academic citations, these notes are often wide-roaming discussions of topics mentioned in the text. So, for instance, R. Austin Freeman’s worry that fingerprints could be fabricated gets this elaboration in an endnote:

Fingerprinting was used by Scotland Yard from 1901, but Sherlock Holmes examined for a thumbprint eleven years earlier, in The Sign of Four. In the US, fingerprint identification was central to the plot of Pudd’nhead Wilson, by Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens). But Freeman feared that reliance on uncorroborated fingerprint evidence could lead to miscarriages of justice. Hammett’s story “Slippery Fingers” reflects a similar concern, and some experts share it to this day (113, n8).

The dozens of reader-friendly endnotes offer a wealth of supplementary information, including recommendations for further reading. Any chapter’s supplements could provide scholars a host of leads for further research. These notes typify the generosity of the book, whose vastness conveys not pedantry but an eagerness to share information and excite the reader’s curiosity.

Edwards’ pluralism amounts to more than intellectual generosity. His book’s global sweep illustrates the astonishing fecundity of the genre in varying cultural contexts; it also shows how malleable its conventions are. I think he shows how fertile a tradition of popular storytelling can be–especially when it has the power to cross boundaries of time, place, and language. No reader of The Life of Crime can believe that this genre has run out of steam.

The toolbox

Tom Gauld, The Guardian (9 January 2016) [20].

Most authors surveying the history of mystery discuss the narrative techniques employed by the various schools. Unlike most genres, mystery fiction’s identity depends on duplicitous manipulations of time, viewpoint, and narration. To conceal the crime and its perpetrator, the author must carefully select who knows what and when. The goal is to baffle both the investigators and the reader, with not only clues on the scene but also hints in the manner of telling. Needless to say, those clues and hints may be misleading.

Both Haycraft and Symons dutifully invoked the conventions of Golden Age bafflement. Haycraft treated them as the source of the genre’s distinctive pleasures, while Symons sometimes deplored their reliance on implausibility and coincidence. (He wasn’t, however, as demanding as Chandler, who famously remarked that “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.”) As a writer sympathetic to Golden Age artifice, Edwards is eager to explore the whole range of devices available for mystery plotting. At this level, The Life of Crime is an encyclopedia of creative options available to the genre. Not surprisingly, Edwards’ wide compass shows that many “modern” techniques have distant historical precedents.

Aficionados recognize several ploys: false identity, faked death, slippery alibis, dying messages, equivocal clues, the absent clue (the dog that doesn’t bark in the night-time), the double bluff (X seems to have done it; wait, X is too obvious a suspect; nope, X actually did do it). Edwards goes beyond these to track how storytellers have used multiple narrators to cloud the situation and sharpen characterization. He shows the persisting power of the “inverted story,” the structure that shows the criminal committing the crime and then follows the detective’s exposure of guilt (the Columbo strategy). He devises a new term to accompany the “whodunnit” and the “howdunnit”: the whowasdunin, the plot that withholds the identity of the victim until the climax. This is a wider trend than I had realized. The same goes for the inclusion of letters and diaries in the text, which feels modern to us but actually goes back centuries.

And of course he doesn’t neglect reverse chronology, highlighted in one of those endnotes that can keep you busy for weeks:

This method of storytelling can dazzle, but only if the writers’ craftsmanship matches their courage. The possibilities are shown by Iain Pears’ novel Stone’s Fall, Jeffery Deaver’s The October List and Ragnar Jönasson’s Hulda Trilogy as well as by Simon Brett’s play Silhouette, Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, Harry and Jack Williams’ TV series Rellik, and Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith’s “Once Removed,” a witty and brilliantly economical episode of Inside No. 9 (612n19).

In all, Edwards’ sensitivity to innovations allows his book to be a stimulating source of craft practices to anyone who wants to write a mystery.

Mystery and misery

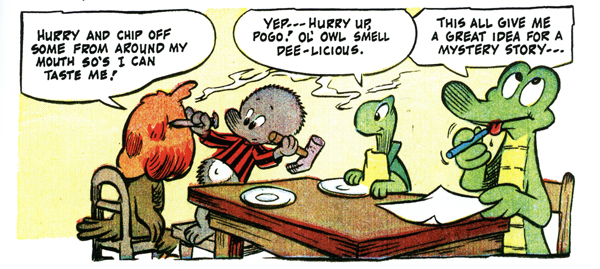

Walt Kelly, “The Big Comical Book Business” (Pogo Possum no. 5, 1951).

Sara Paretsky took up crime writing after contemplating poisoning her husband. Composer George Antheil, outraged by the attacks on his Ballet mécanique, wrote a novel in which barely disguised music critics were extravagantly murdered. Mary Roberts Rinehart refused to make one of her servants her butler, and he retaliated by trying to shoot and stab her. Patricia Highsmith smuggled her pet snails into England by hiding them in her bra, “six to ten per breast.”

At least as intriguing as the crimes in their books are the personal histories of the authors. Edward starts most chapters of The Life of Crime with an arresting account of one writer’s life. It’s often a catalogue of miseries. Alcohol damaged Poe, Hammett, Chandler, Highsmith, Craig Rice, Cornell Woolrich, and innumerable others. Drugs figured in the careers of Wilkie Collins (laudanum) and S. S. Van Dine (morphine). Suicide attempts and mental illness were distressingly common as well.

These usual artworld excesses are enhanced by mystery-mongers’ distinctive dose of weirdness. After a devastating traffic accident, Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gas Light, became obsessed with his brother Bruce. He refused to speak to Bruce’s wife and declared it was a pity that he, Patrick, wasn’t a woman; then he could have married Bruce. Bruce, a mystery writer himself, published a novel called A Case for Cain, in which one brother beats another to death with a golf club.

The juxtaposition of suffering and creative energy is marked. On the brink of financial ruin, morphine-addicted Willard Huntington Wright persuaded a distinguished publisher to issue three mystery novels under the pen name S. S. Van Dine. They sold in the millions and led to a long-running series. Rupert Croft-Cooke, after serving a prison term for homosexuality, fled England for Tangier and published dozens of detective novels under the name Leo Bruce. He also wrote twenty-seven volumes of autobiography called The Sensual World. Agatha Christie’s disappearance in 1926, probably due to temporary amnesia, was a response to her mother’s death and her husband’s infidelity. It didn’t hamper her immense productivity.

With his novelist’s eye, Edwards sympathizes with his subjects, but just reporting the facts still leaves you reeling. Of William Lindsay Gresham he records excessive drinking, occasional violence, and suicide attempts. When Nightmare Alley was bought for Hollywood, Gresham moved into a mansion. “He dabbled in folk-singing, and tried to ease his misery by exploring Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology, and taking an assortment of lovers. On one occasion he’d tried to hang himself on a hook, but it broke.” Years later, he killed himself with sleeping pills. “Legend has it that his pockets were stuffed with business cards bearing the inscription: No Address. No Phone. No Business. No Money. Retired.”

Edwards avoids sensationalism, but it’s good to remind us that much of the entertainment we enjoy was built on a lot of personal pain.

The Life of Crime is, then, a book in four dimensions: reference volume, historical survey, armory of literary techniques, and biographical accounts of major artists. To succeed with any one of these is remarkable; to succeed with all of them is something of a miracle. It will remain an indispensable guide to its subject.

Full, if belated disclosure: I read Martin’s book in manuscript and offered some comments, for which he kindly thanks me. He has also provided an endorsement [22] of my forthcoming Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. [23]

The Life of Crime is already getting splendid reviews in the press and on the Net. There’s an illuminating interview with Edwards on the American Scholar podcast. [24]

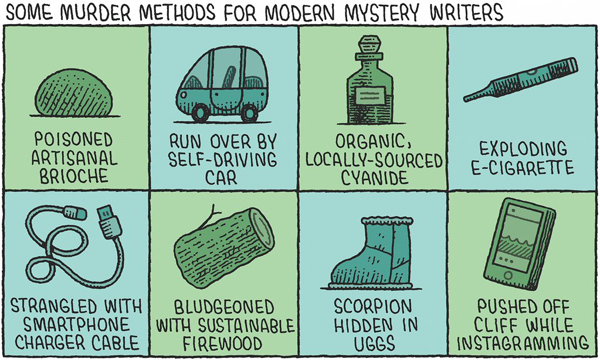

You’ll find plenty of funny cartoons on writing, including writing mysteries, from Tom Gauld here [25]and here [26].

Martin Edwards. From the Warrington Guardian [28].