Children of Divorce (1927)

Kristin here:

In 2008, David and I attended Il Cinema Ritrovato for the sixth time. The Hollywood director being featured that year was Josef von Sternberg. We saw some of the gorgeous prints on show, most notably (for me), a chance to re-watch the underrated Thunderbolt (1929), his first sound feature. To us the big auteur of the year, however, was Lev Kuleshov. Astonishingly, we only blogged from the festival once that year [2]. It was a busy summer.

We and a great many other festival-goers lined up to see one of the rarer items on the program: Children of Divorce, credited to Frank Lloyd but with reportedly about half the footage re-shot anonymously by von Sternberg. We and a considerable number of those festival-goers did not get into the auditorium. For some reason this rare, legendary film was shown in the smallest venue, the Mastroianni, which was packed, with the two side aisles full of standees. (See the bottom image of our blog from the festival [2], as we caught a glimpse of those lucky enough to get in before retreating to find something else to watch or perhaps to wander around the always enticing Film Book Fair.)

Eight years later, in 2016, Flicker Alley released a Blu-ray/DVD combo of the Library of Congress’ 4K restoration of Children of Divorce. That two-disc set is out of print, but last month a MOD (manufacture-on-demand) version was made available [3]. It is a single disc, Blu-ray only, and its main supplement is a pretty good one-hour documentary on Clara Bow produced in 1999 for TCM. (The original booklet is not included.) Somehow we missed the original release, but now I have a chance to catch up with this elusive film.

Naturally I wanted to find out if any information on which scenes of the film von Sternberg re-shot were available, I looked at various internet sources, including books in our library the reviews of the original 2016 Flicker Alley release and books. I found nothing on the subject, not even from film buffs speculating on the basis of style which scenes were his. I suppose one reason why so little discussion of von Sternberg’s contribution is that for many viewers and purchasers of the Flicker Alley discs, this a Clara Bow and Gary Cooper film. Those online reviews from 2016 focus on them rather than on the two very different directors of Children of Divorce. The third star, Esther Ralston is excellent as Jean, and in 1929 she would go on to play the title character in The Case of Lena Smith, Sternberg’s last silent film, which survives only in a fragment. Still, she doesn’t have the lingering reputation and devoted following that her co-stars still enjoy.

Spoilers ahead, including a revelation of the ending.

Von Sternberg’s account

In trying to discover von Sternberg’s contribution, we seem to be entirely dependent on von Sternberg’s sketchy recollections of his work on the film in his memoir, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). Needless to say, one cannot take his account as the unvarnished truth, but it may contain some elements of that commodity.

According to von Sternberg, B. P. Schulberg, head of Paramount, asked him to watch a film that the studio considered unreleasable. Could von Sternberg could improve it by adding the sort of clever intertitles that he was then known for?

I looked at the film as he requested. Its title was Children of Divorce, and it had been made by a prominent director, Frank Lloyd, normally an effective director of commercial films. This one was a sad affair, containing theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow, the “It” girl of her day. I reported back to the executive who had backed this venture with a million dollars, and told him that no skill of mine could restore life to the film by injecting text into the mouths of the players. I suggested that half the film be remade.

That Lloyd should fall down so badly seems odd, given that he had been cranking out films at a rapid pace since 1915. These included films that would be considered star vehicles and adaptations of popular literature, such as the first version of The Sea Hawk in 1924. He would soon go on to win two early best-director Oscars, one for the Greta Garbo vehicle The Divine Woman (1928) and one for Cavalcade (1933), as well as being nominated for what is probably his best-known film, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)–which won Best Picture despite not winning any other of its seven other nominated categories. Cavalcade often shows up on lists of the worst films ever to won the highest prize, but nevertheless, it seems odd that a director so respected within the industry that he won an Oscar for a film made the year following Children of Divorce‘s release should fall down so badly in creating the latter. We shall probably never know what cause this strange failure.

I must admit to never having seen a Frank Lloyd film, but von Sternberg’s assessment of him as an “effective director” seems lukewarm. It suggests that although Lloyd was a good, solid Hollywood practitioner, he had created an unwonted lemon.

In assessing the verity of von Sternberg’s account, we should pause over von Sternberg’s claim that Children of Divorce had had a million-dollar budget. That was well above the average cost of a film in those days. (Von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives, with its giant Monte-Carlo set, had gone over budget to become the first million-dollar film in 1922, and Universal head Carl Laemmle made the best of the situation by blazoning the extravagant budget in publicity for the film.) The original costs estimate sheet [5] on Flicker Alley’s site, along with other documents from the film’s production, puts the total budget at $334,000–pre-re-shoots–a far more plausible sum. Possibly, writing in the wake of the scandal over the cost overruns leading to an estimated $44 million budge for Cleopatra (1963), he had to boost the paltry-sounding budget of a late-1920s feature at least to seven figures to show that he was doing an important favor for Schulberg.

In response to von Sternberg’s suggestion that half the film be remade, Schulberg (according to von Sternberg) said that he could not allot another five weeks to making changes in a project that still might flop. Von Sternberg writes, “I carelessly replied that I could remake half the film in three days and turn over a successful version to him.”

Schulberg asked, “What can I do about the sets? They’ve been torn down and the stages are full.”

Again according to von Sternberg, “I told him to have a tent erected for use as a stage and to dig out the sets from storage, and not to bother about anything else.” Schulberg agreed.

Von Sternberg’s entire account of the process of re-shooting the scenes runs as follows:

The tent went up and the transfusion began. A rainstorm came and lasted three days and three nights. We waded through the new scenes, now and then dodging a heavy burst of water that penetrated the canvas overhead. The crew that helped me and the poor actors that I mercilessly put through their new paces had to take a prolonged rest cure when I had finished with them. To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director. The assignment was completed on time and, after removing the old scenes and replacing them with the new material, I showed the film to the flabbergasted executives.

This tells us discouragingly little. The weather and the cast’s exhaustion make for a dramatic tale but tell us nothing about the film itself. The only statement of interest is “To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director.” Von Sternberg certainly knew the well-established norms of Hollywood filmmaking and if he deliberately set to blend his work into an existing film, his style could be difficult to detect. After all, we don’t know exactly what was wrong with the original version. Bad performances? Von Sternberg’s reference to “theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow” suggests that this may have been the case. Bad storytelling? Von Sternberg doesn’t mention whether he re-wrote any of the scenes he revised.

The new version premiered on April 2, 1927. Von Sternberg was not paid for his labors (he says), but he did prove himself as a director. Schulberg allowed him to direct an entire feature himself. Later that year, on August 20, his first silent masterpiece, Underworld [6], came out. This item in Variety of March, 1927, [7] seems to confirm the basic claim of von Sternberg’s account. Several trade papers mentioned that Sternberg had re-shot some scenes, but none specifies which ones.

Briefly, Children of Divorce concerns two girls whose recently divorced parents have dumped them in a convenient French convent to be cared for. The parents return to the free life of single people, visiting their daughters infrequently. Kitty, a frightened, lonely girl, befriends the kindly Jean. Kitty introduces Jean to Teddy, an old neighbor of Kitty’s. Teddy and Jean hit it off and promise to marry as adults.

Kitty grows up and becomes Clara Bow. She is poor and must give up her love for the noble but impoverished Prince Ludovico (Einar Hansen) to pursue Teddy, now grown up to be Gary Cooper and very rich. His meeting with the grown-up Jean (Esther Ralston), herself now described as the richest woman in the USA, rekindles their love. Despite knowing this, Kitty uses the occasion of a drunken party to trick Teddy into marrying her, and they have a daughter.

Teddy wants to divorce Kitty and marry Jean, but insists that the daughter must not be as they were, a child of divorce. Kitty thinks this would free her to marry Ludo, but he informs her that his religion would not permit him to marry a divorced woman. She determines to hold onto Teddy. Jean decides to marry Ludo, thus quashing Teddy’s hopes of marrying her. Pure misery abounds–all the result, one way or another, of divorce.

What did von Sternberg do?

Naturally one would wish to know which scenes are Lloyd’s and which Sternberg’s. In her brief program notes for the film in the Bologna catalogue, Janet Bergstrom confidently comments, “You can’t miss the shadow language of his scenes.” Perhaps not, but there are actually very few Sternbergian shadowy shots in the film, and those are often brief touches. Here are the main examples. The second scene of the film shows the young Kitty (later to grow into Clara Bow) during her first night in the French convent where her newly divorced mother has dumped her (bottom). In another such atmospheric shot, Teddy reads Jean’s letter refusing to marry him if he divorces Kitty (top).

Other such shots occur occasionally. When Teddy and Kitty’s daughter totters winsomely down the stairs during a party, the elaborate railing casts a shadow over her. Jean’s first sight of her fixes her determination that for the sake of the child she will not agree to marry Teddy if he divorces Kitty.

These are the only shots that one could argue contained strongly Sternbergian shadows. The opening scene in the convent as Kitty’s mother leaves her has a shadow of an offscreen window on the wall at the center of the shot, but surely one could not be certain that an image directed by Lloyd could not have such a modest shadow simply to create the atmosphere of the setting.

Indeed, it seems like a typical shot from an A picture of the mid-1920s.

I do not think that one can determine which shots and scenes were redone by von Sternberg just by the lighting. “To match the scenes I wished to retain,” von Sternberg must have used the three-point lighting system that had been established as the norm during the second half of the 1910s. He did a very good job, and there are many scenes that look like they could have been shot by Lloyd or Sternberg, adhering to that same norm and of course using the same sets and costumes. Which of the two directors made this image, with its exemplary use of the three-point lighting system devised by Hollywood practitioners in the second half of the 1910s?

Von Sternberg’s reference to Lloyd as an “effective” director may sound like diplomatic, lukewarm praise, but he might have meant that any good Hollywood director with an experienced cinematographer could have produced such an image, with its perfect blend of key, fill, and back lighting.

Similarly, we might be tempted to identify this glamor shot of Ralston as directed by von Sternberg, but it seems a fairly conventional approach to filming a beautiful star in the late 1920s.

And here’s an impressive depth staging in the scene where Luco tells Kitty that he could never marry a divorced woman for religious reasons.

It is tempting to think that the stark juxtaposition of a sharply in-focus foreground cut off from the soft-focus background by the edge-lit fringes on the curtains is a von Sternbergian touch, but we cannot be certain that Lloyd and a good cinematographer could not create the same effect.

A possible, probable von Sternberg scene

The big climactic scene sure looks like a very skillful director made it. One is tempted to say that that director was von Sternberg.

The action brings to a head Kitty’s machinations. Having been rejected by Luco, she realizes that her refusal to let Teddy and Jean be together is making them miserable and is not the best thing for her daughter, either. She writes a suicide note addressed to Jean, hugs her daughter for the last time, and heads into her bedroom clutching a bottle of poison.

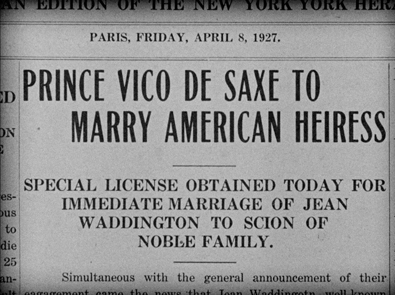

Here is a breakdown of the scene. It begins with Kitty reading a newspaper. We see her point-of-view, revealing that Luco is going to marry Jean. Luco has already rejected her, but this scene is the moment when she learns that he is to marry her friend. The newspaper shot is followed by a closer view of Kitty.

She looks up and to her right, her face grim. It is notable that Bow has been de-glamorized for this scene, with her eyebrows minimized and her hair swept back from her face in a matronly style quite different from her usual bouncy curls. The camera pulls in toward her until it is in extreme close-up.

The pull-in reveals a tear that has slid down from her right eye. It is worth pointing out that this is Clara Bow, noted for her flapper image, always lively and carefree. Clearly she could play drama and even melodrama. Perhaps this is an instance of von Sternberg’s famous ability to direct female performances.

The intense close view is interrupted by a cut to Kitty dropping the newspaper. A long shot follows as she stands and moves to sit down at the desk. A cut-in to a medium shot shows her thinking and beginning to write.

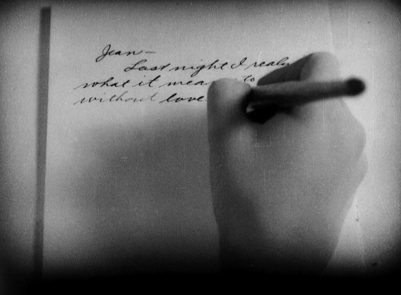

This leads to her point-of-view on what she writes. We learn only that it is a letter to Jean and that Kitty has had a realization. A return to the medium-shot framing shows her reacting to a knock at the offscreen door and saying, “Come in” as she hides the letter under the desk-blotter. An eyeline-match cut shows her daughter entering. A pan follows as she crosses to the desk and Kitty kneels to embrace her.

A cut-in shows Kitty emotionally embracing the girl. During the course of this, the girl’s hat falls off. In a return to the medium-long shot, Kitty carries the girl to her nurse. Another shot shows her returning to fetch the fallen hat and hugging it while displaying despair.

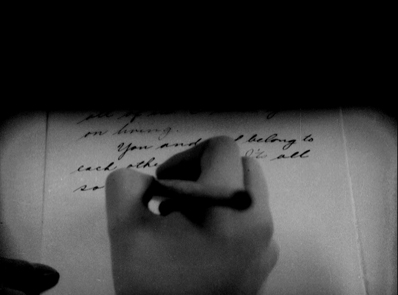

A more distant framing shows her putting the hat back on the child. The nurse’s cheery expression as she helps put the hat on contrasts greatly with Kitty’s unnoticed emotion. Once the others leave, Kitty returns to sit at the desk and pulls out the unfinished letter. Again we see her point-of-view as she completes the letter and we realize that it is an apology and suicide note, telling Jean to marry Teddy and raise the daughter that should have been hers. A return to the medium shot shows her putting the letter into an envelope.

A rather clumsy and unnecessary cut-in to a tighter shot of Kitty might suggest a blend of Lloyd and von Sternberg footage is occurring, but the lighting on the set, Kitty’s hair-do and costume are identical, so the footage is probably all from the same director. A return to the previous medium shot shows Kitty hesitating as she finishes addressing the envelope and presses a button to summon a servant. A cut back to a more distant shot shows her rising and starting rightward toward the door.

A cut to the doorway shows Kitty handing the envelope to a maid, who leaves. Kitty than moves away from the camera to reach for a small cabinet on a table. A cut-in with match-on-action shows her unlocking the cabinet and taking out an object barely recognizable as a small bottle.

A cut to the mirror above the cabinet shows Kitty looking at herself, with the image of her face going out of focus. A cut to a medium-long shot leads to the camera panning with Kitty as she moves to a door at the rear.

She opens the door and walks into the distance as the camera tracks slowly back.

That’s a pretty flashy scene, and it certainly seems more likely than not that von Sternberg directed it.

Once again Flicker Alley deserves credit for bringing us another important film from the silent era.

Thanks to our friends at Flicker Alley for facilitating this entry.