DB here:

Donald Trump did not lose the 2020 U. S. presidential election. He was inaugurated on 4 March. Joseph Biden was arrested and executed. [2]

Or, if you like: Trump will be sworn in on 20 March, [3] the anniversary of the founding of the Republican Party (in Ripon, Wisconsin). Or Trump is President already [4] and working with the military to prepare the mass executions of Democrats [5]. Meanwhile, the Pope was arrested, [6]or will be.

These are among the many lies and delusions promulgated by fantasists, particularly QOnan (not a typo). But these are also narratives.

Narrative in many manifestations, from jokes to comic books, is one of my keen interests. While mostly studying storytelling in film, I noticed some years back how the term and concept of “narrative” became a part of political discourse. I used that buzzword as a path into analyzing the yarn-spinning around presidential campaigns (here [7] and here [8]) and, inevitably, stages in the fascist coup attempted by the fumbling but indefatigable Trump regime (here [9] and here [10] and here [11] and here [12]). The coup effort continues, now at the level of Republican state legislatures.

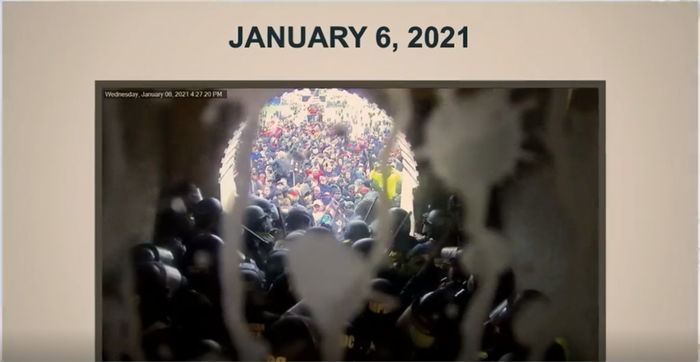

The 6 January assault on the US Capitol, an atrocity many of us followed in real time, has been recast as different stories. The versions range from treating it as an escalation of Trump’s seething rallies to brazenly caricatural accounts, notably the version promulgated by my senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin), a man of invincible ignorance. The versions I want to look at are those laid out in last month’s impeachment trial (Trump’s second) by the Prosecutors from the House of Representatives and the ex-president’s legal Defense team.

The trial began on 9 February with consideration of whether the Senate could impeach a President no longer holding office. That issue was settled by a vote that impeachment could proceed. The trial proper began on 1o February. The charge was that Trump incited the riot that led to the invasion of the Capitol on 6 January 2021.

On 10 and 11 February, the House Impeachment managers presented their case. On 12 February, the Trump attorneys presented their defense, after which both sides entertained questions from senators. The final day, 13 February, was taken up with debates about whether witnesses and further testimony would be invited. After that was resolved, the proceedings ended with a vote on conviction. Sixty-seven votes would have been enough to convict Trump, but only 57 votes for that outcome were cast. Trump was acquitted.

Trump’s original speech to his followers is transcribed here [13]. Official transcripts of the Senate sessions are available on the Congressional Record site [14]. A video record of the proceedings, with good quality on the video clips, is on the C-Span site [15]. This also includes a rolling transcript.

Both sides used film to make their arguments. The House team promised what the press called “a fast-paced cinematic case,” [16] and the Defense responded with pieces of cinema of their own. What resources of cinema did they use? And how do the uses differ?

Narratio as you like it

In Film Art: An Introduction, Kristin and I contrast narrative form with other options. We suggest that a film (or a literary text or a TV show, etc.) could be organized in various ways. Take whales. Using categorical form, you might provide a taxonomy of whales. Using rhetorical form, you could make an argument about whale conservation. With associational form, you might provide a poetic meditation on whales as metaphors for strength and grace. With abstract form, you might film whales in ways that turn them into pure patterns of imagery and sound. And using narrative form, you might tell a story about how a stubborn young girl helped get a stranded whale back into the sea.

Any given film could combine these principles. An argument for conserving whales could include sequences that give us information about genus and species, while other sequences could poeticize the great behemoths in the Whitman manner, or let us appreciate their abstract beauty. Since we all like stories, there will be a strong temptation to “narrativize” when we can. Even a film that tries to make an argument is likely to include some passages involving agents and actions, goals and obstacles.

A rhetorical film doesn’t have to include a narrative component, but it may well do so. Our example in Film Art, Pare Lorenz’s The River, relies on the classic rhetorical structure of problem/ solution. But inserted in that structure we find stories about how the Dust Bowl came to be a disaster area and how the government has taken steps to improve things.

A court case is a prototype of rhetoric. Aristotle accorded little importance to storytelling in forensic rhetoric, but later thinkers recognized the powerful role that it plays. Theorists came to call narratio the portion of the argument that tells the story, or rather competing stories, of the matter in dispute.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that we shouldn’t be surprised that the House Prosecutors and the White House Defense team would float some stories. But what stories were told? How did the advocates tell them? Do the presentations push beyond narrative to other types of form? And what implications do these strategies have for how political actors use moving-image media?

To analyze the cinematic strategies at work, it’s useful to know how they further the broader cases being made. So for each side, I’ll try to show how its use of cinema grows out of its general rhetorical/narrative strategies. Beyond that, we are in a strange re-creation of the situation dramatized in Fritz Lang’s staggering Fury (1936), a film for our moment if ever there was one. There people accused of lynching a man must watch a courtroom screening of their actions during the crime.

Needless to say, there was much less self-examination shown by Republican senators when confronted with powerful sounds and images showing the fury they unleashed and did nothing to forestall.

Witnesses, plenty, for the prosecution

Analyzing a piece of rhetoric demands that the audience be considered. Since rhetoric is centrally about persuasion, how is the argument shaped to suit the audience’s inclinations?

Almost no one expected that Trump would be found guilty, so were the House’s efforts to mount a case a hollow exercise? I think not. The House advocates, it seems to me, were addressing two audiences: the general public and, to put it grandiosely, history. Representative Jaime Raskin and his colleagues treated the matter as a criminal case, offering a detailed reconstruction of motive, method, and opportunity. Assuming that future analyses would be skeptical and rigorous, looking for holes in the Prosecution account, they tried to make it tight, evidence-based, and the most plausible explanation of the events of 6 January.

Their account can be revised in the light of new information (such as recent findings of who funded the rally [21] and how it was coordinated with the White House [22]). Still, it aspired to be a reliable first draft of the most accurate and comprehensive story of the event. The managers injected emotion into their account by emphasizing the casualties of the melée, the narrow escape that legislators made, and the damage to American ideals when the seat of government was ravaged.

The Prosecution accordingly constructed a complex, time-looping, “novelistic” narrative. Taking advantage of the primacy effect, they laid out their story in a dense fifteen-minute video at the start of the first day, during the argument about constitutionality. I’ll consider that montage shortly, but the crucial point is that it concentrated on the attack, with immersive and brutal footage.

Over the next two days, the House managers spiraled out from the attack footage by means of a plot structure that starts with a crisis. This strategy introduces us to the action just before the story’s climax and then fills in what led up to it.

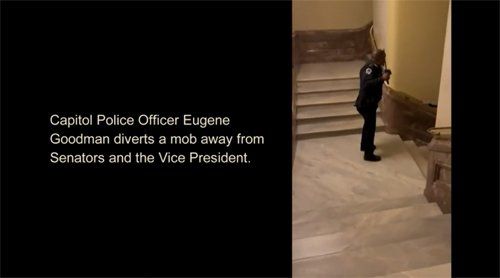

The Prosecutors’ first step was to establish the story’s antagonist, the “inciter in chief.” Trump was put front and center in a flurry of quotes pulled from moments before, during, and after the raid, ending with him declaring to his followers: “We love you, you’re very special.” Who opposed this central figure? Interestingly, the Protagonists initially cast the Capitol police, particularly the black officers who were stunned by the racism they confronted.

Settling on Trump as the gang leader who fled the scene, the House team set out to prove, through detailed timelines, that the attack was “well-orchestrated.” The presentations were divided neatly into parts and chapters. The sections are mostly chronological, showing events leading up to the crisis, though further flashbacks are embedded. The first full day of the case provided a “moving spotlight” narration on the events, roaming back through time and skipping around in space. Thanks to cellphones, we can get a godlike view of the whole event–a crucial choice of viewpoint for the prosecution. I reconstruct the plot as follows.

The immediate provocation: Three messages (The Big Lie, Stop the Steal, Fight Like Hell) were hammered on after the election and then restated as talking points during the rally.

Flashbacks [establishing motive and method]:

Pre-election: Trump announced his resistance to any reports of losing.

Election: On the big night, he tried to stop the counting and declared that he won.

Post-election: He refused to concede, fought in the courts, and tried to round up phantom ballots. After failing to win over reluctant senators and he Department of Justice, he saw Pence as his last chance to overturn the electoral results.

When Pence demurred, Trump sought another avenue for action. He invited his followers to come to DC on 6 January to “stop the steal.” “Will be wild!” “He knew what he was doing.”

The means: Violence. Trump has a history of support of militias and white supremacists (e.g., Proud Boys). His alt-right supporters reciprocated through social media, championing Trump’s Big Lie and declaring 6 January as Armageddon.

[The opportunity:] Back to the 6 January rally, with a split viewpoint: Trump’s speech is intercut with crowd response, using footage from participants’ phones.

Just after the rally: A timeline from 12:20, when the march to the Capitol began, to 2:10, when marchers overwhelmed the police and broke in.

The attack: The timeline continues to the end of the day. Multiple viewpoints provide phone imagery, surveillance footage, and tracking devices to follow the mob’s movements through the building. The assault is crosscut with the responses of police, legislators, and staff. Pence and others were rushed to safety. The mob filled the Crypt, burst into the House, and ransacked the Senate chamber. Outside, rioters boasted of the destruction. “I bled on it.”

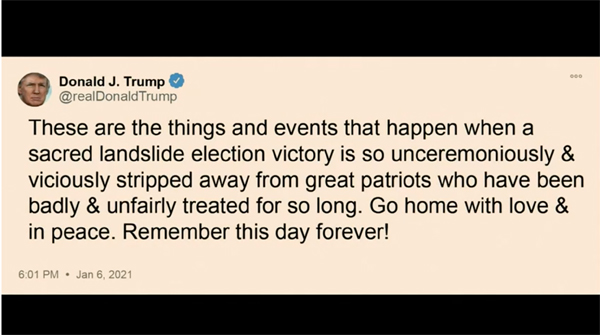

Parallel action: “What was happening at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue?” A new timeline traces Trump’s action from 12:20 at the rally (“I’ll be there with you”) onward. At 2:38 Trump acknowledged the attack in a tweet. Meanwhile, his staff and members of Congress pleaded with him to call the marauders back. At 6:01 he urged the mob to go home and “Remember this day forever!”

Dispersal of the mob: At 7:00 PM the Senate certified the Electoral College vote.

Thus ended the first day of the House managers’ incitement case. The first stretch of the next day was devoted to replaying events from different points of view, as a novel or film might take us into individual characters’ experience.

The rioters’ testimony: Trump had a bond with the rioters. They asserted that he summoned them. “Our President wants us here.” “He’ll be happy.” His control over them was demonstrated when he asked them to go and they dispersed.

Flashbacks establishing the power Trump has over his followers:

Over the years: Trump roused his crowds with insults, making news on TV and nodding to white supremacists. He praised the militias that invaded the Michigan capitol, a “state-level dress rehearsal” for the 6 January siege. Trump did not upbraid the men who plotted to kidnap the Michigan governor; he joked about it at a rally. “This is his essential M.O.”

Trump’s response after the riot: Even after the rampage Trump declared his speech “totally appropriate.” He showed no remorse and failed to condemn the attacks. Even his order to go home was couched sympathetically (“We love you”). His video of 13 January regretting the violence refused to admit that Biden won the election, thus maintaining the Big Lie. Even some Republicans, including former members of his administration, have castigated his failure of duty .

Consequences for the radical right: Most immediately, there was rejoicing on social media (this was “the first stab”) and the riot was proof-of-concept for further missions. There were reports that his followers planned to attack Biden’s inauguration and are continuing to target minority communities. Long-term, this is Charlottesville’s “Unite the Right” rally writ large. Trump has forged a powerful coalition of the fringe groups on the right

Implications for the stability of government: Trump was prepared to sacrifice members of the legislative branch. Through television reports, he knew that everyone, especially Pence and Pelosi, were in mortal danger. While lawmakers were saying goodbye to their families, Trump abandoned his duty. In addition, Trump had no concern for the police or the other staff caught up in the turmoil. Some people were killed and many seriously injured. Ex-service staff called the siege worse than what they had seen in the Middle East.

Implications for national security: Other countries rejoiced at the failure to protect the center of government. (Russia: “Democracy is over!”) Allies were shocked and horrified.

Anticipations of defense arguments (confutatio in the rhetorical trade): This isn’t a Free Speech issue; indeed, Trump launched an attack on the First Amendment. Nor has Trump been denied Due Process.

Conclusion (peroratio): Summing up, with emotional weight added. If this isn’t an impeachable offense, what is?

My outline can’t do justice to the fine-grained detail of the evidence provided in the speeches and the fusillade of images and sounds. I want just to indicate that the argument that a “high crime” was committed and needs to be punished is framed almost completely on the basis of a chronological chain of cause and effect–i.e., a narrative. That narrative indicates motive, method, and opportunity, but these categories of culpability lie beneath the plot we’re given. A man incited a riot by priming the Big Lie, building a violent following, scheduling a provocative gathering during a crucial moment in the transfer of state power, and ranting at a rally.

Beyond the commission of the crime, there is a plea not usually heard in a criminal case. Letting this prominent man off not only sends a harmful message but threatens the future of American democracy.

On the first day, the Prosecutors screened a video that condensed the narrative they propose. While the clip includes some footage not previously shown in the media, it doesn’t include all the new material, some of it quite powerful. Those shots are sprinkled through presentations shown in the following days. The later presentations also recycle many of the shots and sounds presented in this montage, usually to recontextualize them. This montage introduces some of the stylistic methods that would reappear in the days to come.

From Trump’s speech at the rally to his final benediction (“Great patriots. . . .Remember this day forever!”), the video traces a completed arc of action There is no voice-over narrator to guide us, although somber intertitles, white on black, frame the sections. Similarly, there is no music. We hear only the voices and noises in the scenes, although subtitles are brought in to clarify muddy lines and to stress major turns in the action (“They’re leaving!”).

The overall style is that of direct cinema, where the technical roughness conveys the authenticity of events caught on the fly. While some news reportage is included, there’s no editorial comment or punditry. The fact that most of the footage was recorded by the rioters themselves adds conviction. Later presentations will draw on surveillance video to provide a more detached perspective, but the immediate purpose is to immerse us in the participants’ viewpoints. Their blasé attitude toward chronicling their crimes will support the Prosecution’s claim that they believed they had the president’s permission to invade the building and fight for him.

From the start, the video stresses the almost mystical bond between Trump and his supporters. Like Lang’s courtroom scene in Fury, the rally is cut to show both the event and the crowd’s reaction. In eyeline-match editing Trump’s acolytes respond eagerly to his words. After he says go to the Capitol, they reply, “Take the Capitol!” Later his speech is played over shots of their march–the sort of “sonic crosscutting” pioneered by Lang, again, in M (1931). When POTUS says he hopes Pence has the courage to reverse the electoral count, we cut to a shot of Pence. Soon enough the rioters will take up the call: “Traitor Pence!” It’s all part of a single chain of causality.

The Prosecutors anticipated that the Defense would play up Trump’s pro forma aside that the demonstration should be peaceful. But what exactly were the demonstrators supposed to do at the Capitol? To show that violence was really their only plausible option, “Stop the Steal” becomes a unifying thread of the piece. Announced by Trump, picked up by the crowd, and flashed before us in signs and hollers during the insurrection, the phrase suggests not a strategic plan for later primary campaigns but a demand for an immediate tactic, something short and sharp to halt the electoral process.

Crosscutting to show simultaneous events is central to the video’s style. Crosscutting links Trump’s speech to his crowds on the march. It broadens out to trace, for the sake of suspense, many fronts in the assault on the Capitol. While Mitch McConnell rebuts the Big Lie, crowds burst over the barriers and pound on police. Images of the panicked legislators and staff alternate with events elsewhere in the facility, with the danger coming ever closer. Moreover, thanks to some slight sound bridges, the editing gives the impression that the mob is just out of frame in certain shots of the House and Senate chambers.We aren’t far from Griffith’s celebrated crosscutting in The Lonely Villa (1909) and other last-minute-rescue plots.

Just as important, the crosscutting anticipates the parallel timelines that the Prosecution will flesh out in the days to come. Another method, that of split-screen commentary and comparison, is established; it will become useful for yielding the God’s-eye view central to the Prosecution’s case.

The video saves the most harrowing footage for its climax, as we see the rampaging mob battling police in the corridors. Ashlii Bobbitt is shot dead. Handheld imagery from the packed crowd records brutality at close quarters. Shots of the raiders hurling themselves forward in unison are intercut with shots of a guard crying out when his head is pinned in a doorway.

The epilogue takes us back outside the building. Trump’s video calling for peace is undercut by savage assaults on police on the front steps. Throughout, occasional shots of seething bystanders on the sidewalk have functioned as an ominous chorus (“30,000 guns”/ “Next trip”). Now the video ends on the sidewalk, where an alt-rightist calls for assaults on state governments. A title summing up the seven deaths that resulted from the attack is followed by a shot of Trump’s tweet, bookending the opening, thanking the raiders.

In the days afterward, the Prosecution’s case became an audiovisual one; in the age of Powerpoint, verbal arguments are supported by the evidence of images and sounds. Slides of tweets, Facebook pages, news headlines, and other texts were added to a surge of video clips, along with audio recordings from the beleaguered officers. The direct-cinema quality of the material is amped up by the presentation of body-camera footage from an officer beaten down by the mob.

The fallen-camera convention of pseudo-documentary films (like, say, Cloverfield and Georg [27]) wouldn’t be as powerful if we didn’t know that in violent situations like this, cameras–and camera wielders–do drop. In this instance, the approximate optical POV of the stomped officer makes his attackers seem even more brutal.

The Trump Defense team will claim that the senators know all about what happened and so don’t need to have the entire attack played over and over. But the Prosecutors maintain that in fact we still don’t know a lot, and at the time nobody had a view of the whole drama as it unfolded. That’s the rationale for the timelines, for all the crosscutting and side-by-side juxtaposition of images of things happening at the same time.

This omniscient viewpoint is crucial to the case, and is seen with particular density and vividness during Delegate Stacey Plaskett’s use of visual evidence to complement legal documents. She mobilizes Facebook posts, surveillance footage, audio recordings from barricaded staff, and scale models to trace the rioters’ progress through the building. The section is capped by a confession from perhaps the most famous perp.

These God’s-eye views give a new meaning to the crosscutting initiated in the opening montage, filling in both specific locations and moment-by-moment changes in the rioters’ positions. The bonding of the mob with Trump is recalled when one uses Trump’s nickname, “Crazy Nancy.” And the scrutiny of the footage yields details like the stun gun carried by Barnett, aka Bigo. (Bigo, who “will not back down,” is now apprehensive about his prison stay [28].) The sweeping range of knowledge is counterbalanced by moments of intimacy, such as the whispers of staffers into their phones.

One advantage of the House managers’ omniscient framing is to mark out two layers of complicity. The parallel timelines make Trump’s actions during and after the assault integral to the act of incitement in the rally. As with an arsonist who sets a blaze and then sticks around to watch and impede efforts to put it out, Trump’s dereliction of duty is presented as of a piece with what Mitch McConnell would later denounce as his “provocation.”

Apart from the feelingful appeals of the succession of speakers laying out the case, the aggressiveness of the action captured in imagery and sound (the thudding doors, the babble of obscenities) and the panicked voices of police and staffers calling for help intensify the emotional dimension of the case.

Playing the Trump card

The Defense team were also playing to the general public, particularly the right-wing media. But their chief audience was the Republican senators, who needed a peg to hang their inclinations on. Declining to offer point-by-point rebuttals of the Prosecutors’ case. the Defense presented a wide-ranging batch of arguments, a buffet of options rather than a tightly focused throughline. There are some sketchy counter-narratives in there, but they’re accompanied by other points, some legalistic, some evidentiary, and some simply suggestive.

The governing emotion, I think, was barely controlled outrage. The House charge, the Defense maintained, reflected a deep hatred of the President and the ordinary Americans he represented. The impeachment was an act of “political vengeance.” While the Defense often said that it would be better if everyone simply calmed down, there was little doubt that the best response to the purported Democratic intemperance was equally fierce counterattack.

Trump’s Defense team relied heavily on arguments of principle. They didn’t try to refute the Prosecutors’ narrative. Indeed, they simply chopped off large stretches of it. They agreed that the sacking of the Capitol was “horrific,” but all the violence there was irrelevant to Trump’s case. The real perpetrators must be rounded up and brought to justice. If he didn’t incite the attack, then he’s not responsible, and all the shocking footage, all the timelines and tracking of the mob, is so much sensationalism.

How to show he did not incite the attack? Mostly by appeal to categorical form. For one thing, the Defense wanted to explore the relevance of two legal concepts. These the Prosecution correctly anticipated in its pre-rebuttal.

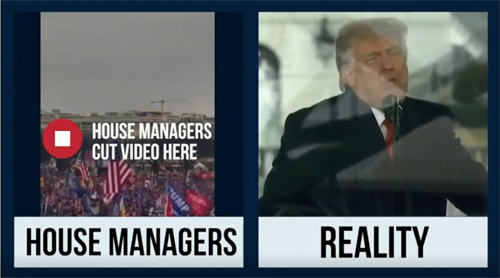

First, the Defense team asserted that Trump was denied Due Process on many grounds. Evidence that would be challenged in court was put forth as reliable. Video clips were edited to omit statements in Trump’s favor, and some of the slides of tweets had errors in dating or attribution.

The House evidence of Trump’s encouragement of violence was likewise claimed to be selective and taken out of context. Trump is a man of peace and he has never stoked anger–unlike the Democrats who in many speeches have indulged in hateful rhetoric. Nor is questioning an election result inherently inciting; many Democrats claimed that the 2016 election was stolen.

All this mitigating evidence would have come to light had Trump been given Due Process. Witnesses would have been called; depositions would have been taken; the Defense could have interrogated those accounts. As presented, the case for incitement would not stand up in any court. It is a prime example of the category “Politically motivated injustice.”

Second, Trump was said to be simply exercising his First Amendment rights. Contrary to the opinions of the 140 law professors who declared that Trump’s remarks fail as Free Speech, his statements at the rally are, perhaps lamentably, within the range of current public discourse. His urging his followers to fight simply echoes what Democrats have told their crowds on many occasions.

The Defense videos, fewer in number than the Prosecutors but recycling many shots several times, were designed to drive home these points. Significantly, the first video was designed to establish the “political vengeance” motive.

Apart from ascribing a vendetta to the impeachment initiative, this montage sets up the impromptu category of “Currently acceptable political discourse.” Specifically, the clip plants the “fight” motif that will dominate the later proceedings. It also prepares us for the throbbing music that will underscore the big sequence to come.

The Defense began by bracketing off the entire insurrection, explaining that they wouldn’t be showing footage of it.

They [the Prosecutors] don’t need to show you movies to show you that the riot happened here. We will stipulate that it happened, and you know all about it.

The Prosecutors’ embrace of the omniscient perspective sought to show that none of the legislators could have “known all about it” then or even now. But the Defense’s dismissal of the entirety of the sacking of the Capitol cleared the way for the case predicated on categorical form. In backing up the argument against conviction, the Defense’s major video sequence assembled samples of prevailing political rhetoric drawn from Democrats’ speeches and statements.

Unlike the Prosecutors, the Defense team relied largely on material from the news media. (Presumably these excerpts don’t count as Fake News.) And, again, the clip is accompanied by throbbing, ominous music evocative of an urban action thriller. If the House case resembled a direct-cinema documentary, the Defense case is stylistically closer to a political ad. All it lacks is a title telling the viewer the sponsor who approved it, and where to send money.

Some of these Democrats’ remarks, taken singly, are pretty abrasive. But although the extremism on display is regrettable, the Defense argued that the Democrats have a perfect right to make them. So does Trump. The Democrats were not telling their crowds to resort to violence, and neither was he.

There is a certain irony in the Trump team’s use of editing to reiterate a concept. It’s a technique we can trace back to other Griffith films, like A Corner in Wheat (1909), but it’s most associated with Soviet filmmakers like Eisenstein and Vertov. The pounding rhythm of “fight, fight, fight” has some of the same force we get in those percussive intertitles in Russian silent classics.

And maybe, the Defense asked, the Democrats aren’t so innocent? A sketchy narrative is invoked in the first sequence above, which arranges statements chronologically to suggest a crescendo of cries for impeachment from the beginning of Trump’s term. The editing of the last montage moves even more strongly toward narrative patterning. Didn’t Democrats’ incendiary rhetoric play some causal role in the summer 2020 civic unrest?

Unlike the Prosecutors, the Defense sequence gives no specifics, no timelines or maps, no link between these sound bites and particular actions in particular places. Many of the Democratic speakers are declaring that they will fight; they aren’t all urging their followers to do so. Unlike the MAGA-blazoned rioters in the Capitol, the street fighters in the videos go unidentified. The episodes of street fighting are a cinematic version of Republicans’ equivalency between Black Lives Matter protests and the assault on the Capitol. This loosely plotted story gives many senators a peg to hang their preferences on.

What happened when the Defense got down to linking up events more exactly? In contrast to the panoramic sweep of the Democrats’ narrative, the Defense scope is very narrow: essentially, just the rally. Apart from some parsing of what Trump meant by “very fine people on both sides” in Charlottesville, there is no mention of his long record of inflammatory remarks. Instead, the Defense constructed a story of what Trump was really asking his crowd to do in that particular speech. They did not try to explicate the many other statements on 6 January, such as the tweet at the top of this section, that congratulate the rioters. The Defense team rewrote the rally as an isolated event, a stand-alone scene whose principal lines demand careful interpretation.

Split screen is used to show the edit points of House videos and to suggest that what Trump said in toto was mitigating.

According to this story, on the day in question Trump was not demanding violence. His call for courage and fighting was simply a request for his supporters to challenge errant Republicans in future elections. If any Trump supporters did engage in the riot, it was because they misunderstood him.

Their error was no greater than that of the Prosecutors, who initially believed that Trump was calling for blood. Once the House managers realized their mistake, Defense attorneys reasoned, they found other pretexts for attacking him. They whipped up the myth of the Big Lie about electoral finagling. Why is it a myth? Because in previous certification ceremonies Democrats accused electors of irregularity as well. They didn’t get away with it because they lacked Senate support and were shut down by the presiding official–in one case, none other than then-VP Joe Biden. Nonetheless, questioning electors’ bona fides, the Defense argued, is not uncommon after a presidential election.

Another, rather sketchy Defense story invoked the possibility that the violence visited on the Capitol was conducted by groups independent of Trump’s control. Some rioters came planning to attack the building and used his rally as a pretext for their mission. They “hijacked the event.” Trump could not incite something that was going to take place anyway. Moreover, some of those people were anti-Trump activists wanting to make mischief. Little evidence of these claims is adduced, but again a proper trial would presumably have brought such information to light.

In all, the people to blame are the Trump followers who misunderstood his message, the alt-right renegades who wanted to make trouble, and the undercover provocateurs from the left. Trump’s remarks, protected by Free Speech, remain distinct from the actions of these troublemakers.

A larger narrative, ultimately more powerful for the public audience, involves motives. First there was Trump’s motive. Trump, on the basis of his speeches, was said to be the most pro-police president in history. He would never encourage his followers to put peace officers in danger. But what about the other side?

Just as the House Prosecutors sought to show that Trump’s desire to retain power made him ever more desperate, the Defense claimed that what fueled this entire proceeding was irrational hatred of a duly elected President. Democrats have “lusted” for impeachment since 2017. The attack on the Capitol gave them the chance to unseat and disgrace him–and keep him from running again. Another montage of quotations, echoing the initial sequence, was invoked. In sum, this is a political trial and the defendant is being railroaded.

The Prosecutors created an intricate narrative centering on Trump and his MAGA army, with those on the other side–from police and staff to legislators both Democratic and Republican–cast as victims. A deadly attack was summoned into existence to keep a man in power. The Defense avoided a long-form narrative but pivoted to categorical organization: Trump’s situation became an instance of denied Due Process, and his tirade exemplified Free Speech in the currently overheated partisan dialogue.

But the Defense didn’t wholly avoid telling a story. It focused on the rally as a single incident that has been misconstrued. And their broader story, probably the overarching one, pits Trump and his patriotic followers against the vengeful Democratic party and its army of summertime hooligans determined to unelect him, and make him forever unelectable.

There’s a lot more to be said about the structure and style of these fraught sessions of the Senate. They will be scrutinized for years by students of law, politics, social change–and, I hope, media. We can bring to the table some tools that allow us to analyze how traditions and conventions of cinematic forms and styles interact with the exigencies of occasion and ideology. They alert us to the ways in which our buttons are pushed and our thoughts and feelings are steered this way and that.

I should say, in case you’re wondering, that I find the Defense case preposterous–sophistic, evasive, streaked with irrevelancies and contradictions. That’s because I side with Aristotle’s view that rhetoric should be a packaging system for sound thinking. Logic and science are truth-tracking, whereas rhetoric makes no discoveries. It is a skill set, a tool kit for presenting ideas and opinions in ways that people will accept. Rhetoric is needed because a lay audience needs help in grasping the premises and conclusions of specialized inquiry. That means, for Aristotle, rooting arguments in not only plausible inference and ethos (trust in the speaker’s moral character, as displayed in the speech) but also appropriate emotional appeals that will engage the audience in the pursuit of understanding.

Ideally, the ideas and opinions set forth are the ones with the best rational and empirical backing. But they may not be. Prejudice, stereotypes, and quick-and-dirty inferences are the rhetorician’s stock-in-trade. Still, we can be on guard against weak rhetoric. Educators could go back to teaching high schoolers the fallacies of informal reasoning; a huge swath of political babble, including the Trump Defense case, exemplifies tu quoque and ad hominem. And when films and videos take rhetorical form, our skepticism can be reinforced by awareness of how movies work. Studying film can alert us to the ways we can be gulled, blinded, or reinforced in our own prejudices.

It can also show how a rhetorical case can rest on a foundation of more or less plausible explanation. That, I think, is where the Prosecutors’ case leads us, thanks to its strict structure of likely cause and effect. But no less than the Defense, the House managers used the resources of the medium to quicken the impact of the documents they assembled. Fortunately, thanks to modern media, those documents are themselves vivid records in the moment. They will remain, after many viewings for decades to come, powerfully convincing–at least, to people of open mind. The question is how many of those people will still be around.

Geoffrey O’Brien has an engaging discussion of the ways current conspiracy theories echo those of earlier eras in “Hitler in Antarctica” at the New York Review of Books site [31].

I discuss the role of the crisis structure in classical American film in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

It may be relevant that I thought and still think that Bill Clinton, a man utterly lacking in personal honor, should have been convicted in his 1999 impeachment exercise.

P.S. 21 March 2020: The New York Times has assembled an astonishing montage of mostly new footage [32] of the combat outside the Capitol, showing the police trying to hold the insurrectionists back. Twelve Republican representatives voted against awarding Congressional medals [33] to these officers. One of those opposing the legislation, Rep. Bob Good, was discovered to have a connection to the riot when it was revealed that his district’s party director and her husband were part of the crowd converging on the facility.

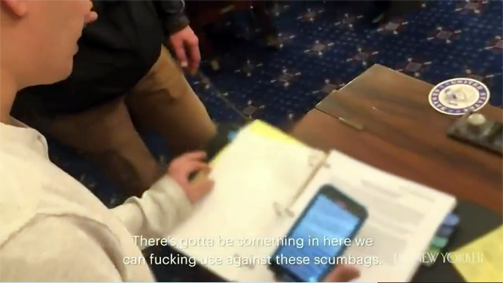

Left: Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) in the Senate Gallery during the impeachment trial; drawing by Art Lien. [36] Right: Extract from Prosecutors’ video montage. The speaker says: “There’s gotta be something in here we can fucking use against these scumbags.”