DB here:

Notorious was the subject of the first piece of criticism I published. The venue was Film Heritage, one of those little cinephile magazines that flourished, if that’s the word, in the 1960s. My appreciative essay came out in 1969, as I was finishing my senior year in college.

I haven’t dared to look back at it. Actually, I’m not sure I have a copy. The soft-focus imagery of memory tells me that some things that would preoccupy me in the future–interest in narrative structure, style, point-of-view, the spectator’s engagement with mystery and suspense–are there, though in ploddingly naive shape.

Since those days Hitchcock has always been with me. He’s been the subject of articles and blogs and many, many classroom sessions. Now, thanks to the Criterion collection, I’ve had a chance to revisit Notorious.

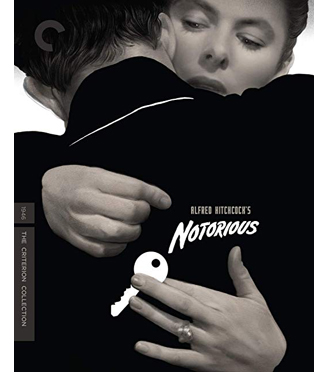

[2]The new Blu-ray edition [3] includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

[2]The new Blu-ray edition [3] includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

Hitchcock is the most teachable of classic directors. His strategies are just obvious enough for beginners to notice them, but they always open up new directions for more experienced viewers.

I reconfirmed all this when I decided to devote a chapter of Reinventing Hollywood to Hitchcock and Welles. These two masters decisively influenced the 1940s, the period I was considering. But they were in turn influenced by the crosscurrents in their filmmaking community. And they came to epitomize, for me, the artistic richness of what Hollywood could do in this golden age.

In addition, I tried to make the case that they carried storytelling strategies typical of the period into later eras. I declared, in a burst of geek recklessness:

Vertigo constitutes a thoroughgoing compilation/revision of 1940s subjective devices. The obsessive optical POV shots of Scottie trailing Madeleine give way to a dream tricked out with pulsating color, abstract rear projetion, stark geometric patterns, and animated flowers. . . . Along with all the other echoes–portraits, therapy for a traumatized man, voice-over confession, point-of-view switches, the hint of a reincarnated or time-traveling woman–the powerful probes of subjectivity make Vertigo, though released in 1958, one of the most typical forties movies.

But then so is Notorious, a film I had little to say about in the book. So I’m glad that Criterion’s invitation to contribute a 30-minute short on this new release led me back to a film I’ve loved for over fifty years.

Darned sophisticated, or dead

My supplement concentrates on the climax in Alicia’s bedroom and on the staircase of Sebastian’s mansion. Spiraling out from that sequence, I try to show how it’s the culmination of many storytelling strategies, from point-of-view editing to long takes. I also trace out something I didn’t fully realize until I researched the film’s reception: It was considered very sexy.

For one thing, Ingrid Bergman was associated with innocents, and her playing a promiscuous party girl (“notorious”) was a bit of spice. For another, Hitchcock’s earlier films, though they always had erotic overtones, didn’t really center on a passionate romance. His heroines didn’t convey much smoldering passion, despite all his prattle about glacial blondes thawing out fast. His darkly handsome protagonists (Maxim in Rebecca, Johnnie in Suspicion, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt) are more steely than steamy. As for Joel McCrae in Foreign Correspondent and Bob Cummings in Saboteur, they seem virtual Boy Scouts. Only Spellbound, which introduces a psychoanalyst to ecstasy in the rangy form of Gregory Peck, seems a first stab at the sexual complications of Notorious. And the analyst is played, of course, by Bergman, radiant as soon as she takes off her glasses.

The 1940s had a well-established convention that a handsome friend of the family could rescue a wife from the predations of her husband (Gaslight, Sleep My Love) or other tormentor (Shadow of a Doubt). Film scholar Diane Waldman called this figure the helper male. In the second half of Notorious Devlin plays this role. The basic situation–a man stealing another man’s lawfully wedded wife–is pretty edgy in itself, especially since Sebastian is far more frankly in love with Alicia than Devlin is. I try to show that Hitchcock wrings new emotion from the convention by making the husband, trapped between his Nazi gang and his ruthless mother, sympathetic. Meanwhile, the helper male comes off unusually cruel, needling Alicia about the carnal bargain he plunged her into.

And then there’s all that snogging. The romance in Notorious is one long tease–between the characters, and between the screen and the viewer. The Los Angeles Times critic made it the basis of his lead:

Devlin and Alicia are all over each other, notably in the famous scene in her apartment. (Have they done The Deed? Obviously yes.) Their tight embrace, their constant pecking and nibbling and nuzzling as they float across the room, provoked a lot of notice. In the supplement I quote Dorothy Kilgallen, whom my oldest readers will remember from “What’s My Line?” on TV. She wrote this in Modern Screen:

So it makes a certain amount of sense for a power company to assume that incandescent stars can sell electricity, as below. In Toledo, too.

For this and other reasons, I’m happy to have a chance to revisit one of my very favorite Hitchcock films. I bet that you’ll enjoy seeing this stunning copy and immersing yourself in all the bonuses. Hitch is endlessly fascinating, and he’s one of the main reasons we love movies.

Thanks to Curtis Tsui, who produced the disc, as well as Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison, and all the New York postproduction team. Thanks as well to Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson for all they do to keep Criterion at the top of its game.

Greg Ruth, designer of cover art for Criterion, explains his creative process on their site [7]. More details on the release, with clip, are here [8].

The Los Angeles Times review comes from the issue of 23 August 1946, p. A7. The Kilgallen Modern Screen piece is available via Lantern, here [9]. If you youngsters didn’t get her reference to Helen Hokinson, go here [10].

For another in-depth analysis of a single sequence, see Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin’s Filmkrant video essay, “Place and Space in a Scene from Notorious.” [11] They showed me things I had never noticed–more proof of the richness of Hitchcock World.

Cary Grant’s image was used to sell oil a few years before, as illustrated in this entry [12].

P.S. 21 January 2019: For more on the steamy side of Notorious, there’s “The Clinch That Filled 1,200 Seats,” [13] at the redoubtable Greenbriar Picture Shows. Thanks to John McElwee for bringing it to my notice!

Better Theatres (24 August 1946).