DB here:

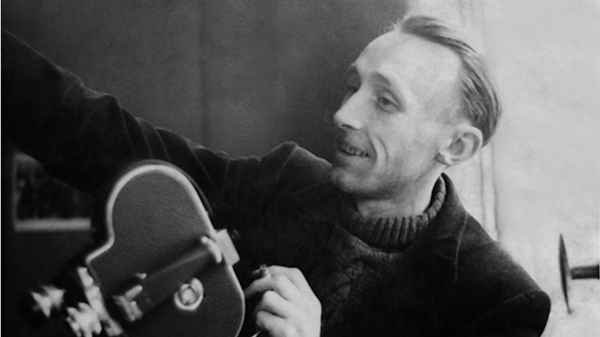

André Bazin was born in 1918 and died on 11 November 1958. In his short life he became, without aiming at it, one of the greatest theorists and critics of cinema.

A central figure in the founding of Cahiers du cinéma, Bazin was also active in building film culture through ciné-clubs and festivals, most notably Cannes and the Festival du film maudit. His writings were poetic, original, and provocative in the gentlest way you can imagine.

As a reviewer he discussed hundreds of releases, and in essay mode he produced subtle reflections on cinema as both medium and art. He wrote about Westerns, pin-ups, Stalinist cinema, documentaries on art and exploration, and of course the commercial storytelling cinemas of France, Italy, and Hollywood. His friendship with two generations of filmmakers–Renoir and Truffaut, among others–gave him a living link to film history. Many would argue that the “young cinemas” of the 1960s, building on both Italian Neorealism and the pictorial styles that crystallized in the 1940s, owe a great deal to the tradition of critical debate he fostered.

Bazin’s thousands of pieces have now been gathered by Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. A three-volume collection is scheduled to appear this week in a deluxe edition published by Macula of Paris [2]. The press kit, with excerpts, is here [3].

Beyond reading the work itself, if you want to know more about the man, I think the best place to start is with Dudley Andrew’s biography [4]. It’s a sensitive overview of Bazin’s life and thought, giving particular emphasis to the philosophical and religious influences on him.

Bazin has shaped my thinking about film history and aesthetics since 1967, when I first read Hugh Gray’s translation of What Is Cinema? [5] I taught his work for decades here at Wisconsin, and in On the History of Film Style [6], I tried to analyze his pivotal role in our understanding of the “development of film language.” That chapter situates his thinking about technique in the context of the “nouvelle critique” of the 1930s and 1940s, a trend that tried to locate an aesthetic suitable for the sound cinema.

Later, I wrote an essay for the German journal montage a/v, [7] which ran a special 2009 issue [8] devoted to Bazin. The original English text, slightly updated, is now available on this site (here [9], and on the left). That piece suggests how Bazin’s thinking has shaped my own approach to understanding cinema.

Commentators pledged to labels may wonder how a “formalist” like me can find common cause with a “realist” like Bazin. Actually, in both method and substance, his work offers much to the research program I’ve called a poetics of cinema. To see Bazin as being “for” deep-focus and the long take and “against” montage is an oversimplification, it seems to me. He saw more deeply and more widely than that, not least because he was always aware that filmic expression—in style, in narrative—changes across history.

Film criticism owes Bazin an immense debt; he taught us to look closely at what’s onscreen. Elsewhere on this site, we discuss some examples (for example, here [10] and here [11] and here [12]).

There are many ways of thinking about his work, as you can see from the swelling number of articles, books, and conferences devoted to him. He remains a tremendous figure, blending modesty, tolerance, patient attention, close viewing, and bold speculation. Film studies could scarcely exist without him.