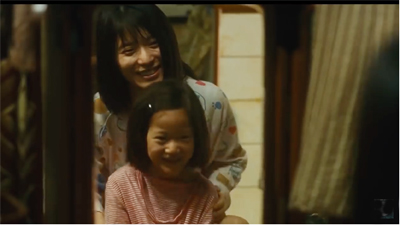

Shoplifters (Kore-eda, 2018).

DB here:

We’ve been attending the Vancouver International Film Festival [2] since 2004. (The entries are tagged here [3].) It’s provided us many of our happiest viewing experiences, and this year is proving just as exciting. In particular, the festival’s long commitment to new films from Asia hasn’t flagged. Thanks to programmers Shelly Kraicer and Maggie Lee there has been plenty to showcase trends in Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, South Korea, and other lands. We won’t, unfortunately, be here for Hong Sangsoo’s Grass, but here are interim reflections on four items that we’ve seen in our first days.

Families, fraught and fragile

Shoplifters.

Girls Always Happy is a quiet but ingratiating first feature from Yang Ming Ming. Mother and daughter are both writers, and they struggle to live together in harmony while hoping for a legacy from Grandfather and for some resolution in their love lives. Yang says that she based the film on her own life, which rings true when you consider the range of emotions that well up. The two women tease each other, insult each other, ravenously devour meals together, shop partly to annoy sales staff, and sometimes burst out in screams. Reconciliations may be temporary but are still heartfelt.

With the two of them jammed together in a hutong, a neighborhood of cramped old ground-floor apartments, their jousts take on an intensity captured by Yang’s exceptionally tight framings and rapid cutting. Yang storyboarded the entire film, which allowed her quite precise control of composition and focus.

The relentless close-ups allow both psychological intimacy and subtle performances, as well as comparison of eating styles. Trips outside—Wu on her scooter or in her lover’s modern apartment, the mother at a hair salon—provide a respite from what’s essentially a series of escalating two-handed combats. The final shot is a lengthy take that carries our heroines forward into their city. Yang explained in the Q & A that after a film full of fast cutting and lots of talk she decided to end with the sort of long take Chinese filmmakers favor. In this context, with a canny use of a bus’s rearview mirror, the shot becomes an exhilarating, floating passage into the Beijing night.

Girls Always Happy came to VIFF garlanded with awards, including prizes from both the Berlinale and the Hong Kong Film Festival. Even more honored was the latest by Kore-eda Hirozaku, The Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s another of his family dramas (we’ve discussed Still Walking [7], I Wish [7], Like Father, Like Son [8], Our Little Sister [9], and After the Storm [10]), but here the notion of family is given an uncanny twist at the end.

Each member, as per Kore-eda’s habit, is given a specific, respectful delineation. There’s the happy-go-lucky Osamu, a day laborer who both coddles the boy Shota and leads him into petty crime. There’s the maternal Nobuyo who works at a dry-cleaning facility and pilfers what she finds in pockets. Twentysomething Aki works at a sex club flashing her breasts and bottom at men crouched behind one-way mirrors. Grandma keeps the group going with her pension, her pachinko-playing, and some secret sources of income. Into this household comes Yuri, an abused child brought home like an abandoned cat.

Like Tsai Ming-liang’s more somber Rain Dogs, this is a film about people on the margins. The kids don’t go to school; Shota teaches Yuri the tricks of shoplifting, while Aki warms to a sex-club client. As in Girls Always Happy, interiors are sharply distinguished from exteriors, but not by close framings and shifting focus. Instead, master shots fill the frame with the detritus of seven people jammed in together. (See shot above.)

In a film so concentrated on characterization, we naturally get the sort of privileged moments that Kore-eda excels in. Osamu pauses in his construction work to stand looking around an unfinished apartment—a modest one, but a home he can never have. The young kids collect cicadas. Aki cradles a lonely punter in her lap. Nobuyo consoles Yuri by comparing the girl’s scars to burns Nobuyo has accumulated from ironing clothes. Grandma, watching her charges play on the beach, pours sand to cover the age spots on her legs. The ensemble comes together in moments of shared joy at the seaside or watching the fireworks at the Sumida River festival.

But these moments don’t prepare us for the unsettling revelations about the characters’ pasts that we get in the last half hour. Even here, though, the details of behavior remain indelible. One astonishing shot turns a cinematic staple—a woman trying to wipe away tears—into a tour de force of facial performance by Ando Sakura.

The Shoplifters reminded me of Ozu’s Passing Fancy and Inn in Tokyo, obliquely but sharply condemning the economic conditions that push people into wayward lives. It’s a gently subversive film about people flung together resourcefully trying to survive and find happiness by flouting the comfortable norms of middle-class morality.

Time out of mind

A Land Imagined.

Lush Reeds, by Yang Yishu, has plenty of the long takes that Girls Always Happy avoids. In nearly abstract framings, newspaper reporter Xiayin moves through minimalist offices and country lanes, bleak apartments and dense foliage.

As in many postwar films [15], drama sometimes becomes subordinate to the walks taken by the protagonist into an overwhelming, mysterious environment.

Against the wishes of her politically cautious editor Xiayin inquires into complaints of rural pollution. At the same time, she’s pregnant and is growing distant from her fairly cold husband. Her visit to the countryside becomes a threatening experience that brings to light parallels between the death of a villager and the apparent suicide of a fellow reporter.

The film is less linear than I suggest. Yang breaks up the story into midsize chunks and sets them out of order, so that some images–a little girl who meets Xiayin in the village, a shoe on a riverbank, the rescue of a suitcase from a rubbish depot–could fit into one time frame or another. Yang is even so bold as to run the title credit again midway through the film, suggesting that what follows might be backstory, or imagination, or an alternative film, or something in between.

A similar ambiguity pervades A Land Imagined (2018), another prize-winner (Golden Leopard, Locarno). It centers on a migrant worker Wang working at a Singapore site devoted to extending the coastline with sand dredged up or brought from other countries. Wang has disappeared, and the investigating cop Lok soon learns that Wang’s Bengali friend Ajit has vanished as well. A flashback takes us into the backstory, showing Wang spendiing his nights at a cybercafé and getting harassed by a troll who invades his videogame screen. Wang also begins a chaste affair with the tough gamine Mindy who oversees the game parlor. Eventually the flashback turns into a parallel, dreamlike narrative, with Ajit by turns dead and alive and Lok reenacting scenes involving Wang.

Director Yeo Siew Hua has given this noirish tale an appropriately lustrous treatment, with saturated long shots of black derricks looming against a red sky or sunk in sickly orange murk. Lyrical slow-motion musical interludes enhance the dreamlike ambience, and there’s a post-Wong-Kar-wai freedom of camera placement in the candy-colored cybercafé.

In his comments after the screening, Yeo spoke of trying to provide a counter-image to “the postcard, Crazy Rich Asians” depiction of Singapore. The shifting time frames and uncertain stretches of subjectivity are connected, for Yeo, with a sleeplessness suffered not only by the main characters but also by the population at large. The “land imagined” isn’t only the sand that expands the contours of the shoreline but also the hallucination of a hypermodern city state built on the labor of workers who can conveniently go missing.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page [17].

Girls Always Happy.