DB here:

I’m back in Madison from 2 1/2 months in Washington, DC. under the auspices of the John M. Kluge Center [2], where I was this year’s Chair of Modern Culture. This kind appointment allowed me to pursue my research into 1910s American film style, than which nothing could be more fun. Along with that were some extramural activities. The most spectacular one was our Kluge field trip into the most overwhelming media archive in the world–the bulging-biceps caped crusader of film, TV, and sound preservation.

Treasures under Mount Pony

Dr. Strangelove could have come up with the idea. If the Russians attack the US, better have a deep underground vault for storing a few billion dollars to replenish currency supplies on the East Coast. So in the Culpeper, Virginia countryside build a gigantic secret bunker. Include facilities for housing 500 or so personnel to keep the government, or what was left of it, running for a month. Add amenities like a pistol range and refrigeration units to cool cadavers that couldn’t be buried outside. Getting assigned here in nuclear winter would definitely count as subterranean homesick blues.

This super-secret complex was completed in 1969. It boasted foot-thick concrete walls and was surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun nests. By 1992, the bombs had failed to fall, so the complex was decommissioned and eventually offered for sale. After a major grant to the Library from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a long-time friend of American film history, the building was transferred to the Packard Humanities Institute . The facility was renovated thanks to over $260 million of Packard and Congressional funding. A lot, yes, but in 2017 dollars that comes to about $402 million, and Beauty and the Beast has scared up about twice that over the last couple weeks.

The renovation turned this vast bank vault/bomb shelter into the world’s most colossal and up-to-date media storage and preservation facility. Opened in 2007, the National Audio-Visual Center is also known as the Packard Campus. Its collection of films, videos, and audio records, along with posters and documents, come to over six million items sitting on ninety miles of shelving. With 80 per cent of it sunk below ground, it was designed to be an exemplary green building, with a vast gardened roof.

Thanks to the energy of Kluge Center director Ted Widmer and his colleagues, we had a chance to visit the place. Greg Lukow, Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus, and Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image section, led us in a labyrinthine, carefully organized three-hour tour of the dazzling facility.

I can’t convey all that we learned about conservation of film, TV, sound recordings, and digital media. Rest assured that the hundred-plus people working away here in state-of-the-art conditions are striving mightily to save media artifacts for you and me and our heirs. Here are some high points.

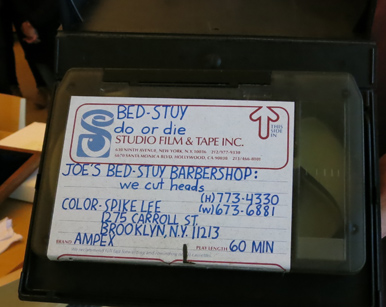

Mike introduced the visitors to the moving-image formats of the media conserved at the facility, everything from film and videotape to Digital Cinema Packages. Spike Lee’s first film, as a copyright deposit, is there too, on Ampex tape.

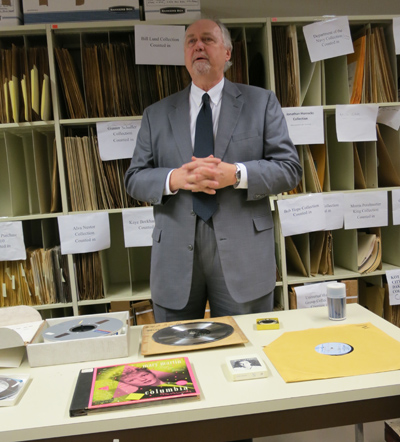

Sound isn’t neglected, as Greg offered a comparable overview of all the audio formats, including cylinder and wire recording. Yes, 8-tracks are also involved. On the right you see the Scully Lathe, a gleaming bad boy that cut disks. Used from the 1930s into the 70s it’s being brought back [5] with the new interest in vinyl records.

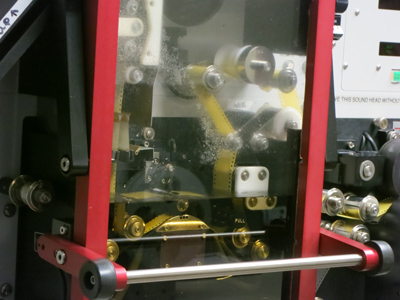

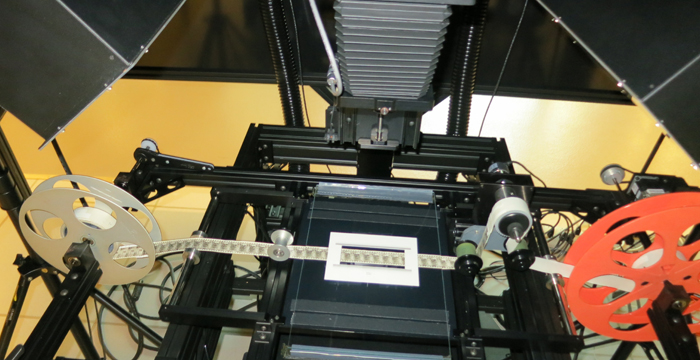

We visited several lab and restoration rooms, including one for wet-gate printing and another for migrating VHS tapes to digital files. Since the latter has to be done in real time, robots are recruited for the job, busily gliding up and down ranks of cassettes.

Of course we had to stop by film vaults, kept a chilly 39 degrees. On the left we see some of the holiest of holies, nitrate vaults. It looks like a Spanish Civil War prison, rows and rows of heavy doors. The vault on the right contains master safety film elements, on both acetate and polyester stock.

What’s a trip to an archive without despoiled artifacts? On the left, a flaking glass-based 16-inch lacquer instantaneous disc from the NBC radio collection. “Instantaneous” means that it was a recording of a live broadcast, and so was probably unique. On the right, we have decomposed nitrate film.

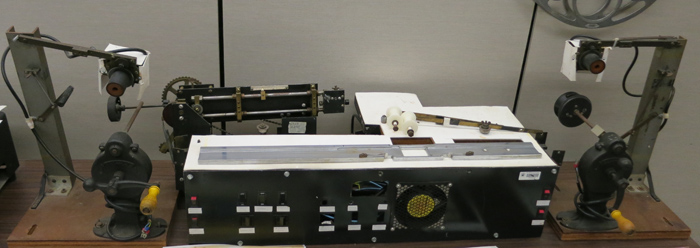

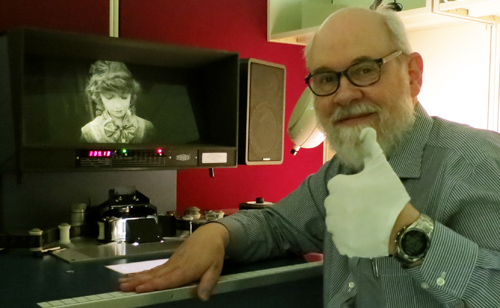

Of enduring interest to cinephiles is the famous paper print collection. Film companies of the earliest years submitted to the Library movies on rolls of paper, to be copyrighted in the manner of still photographs.To be preserved and screened, those had to be turned back into films. During the 1950s that task was fulfilled by Kemp R. Niver in a home-made rig.

He transferred some 3,000 titles to 16mm–not the ideal format, but better than nothing. Some results were fuzzy and jumpy, but many came out okay. I watched several during my stay, including The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914).

Since then, some excellent 35mm prints have been made from the paper prints, and still more success has been found with digital remastering, which can correct for misaligned frames on the original paper copies.

It was good to learn that film copies of new releases are still being submitted for copyright deposit. An impeccable print of Get Out arrived while I was there, and of course 35mm advocate Christopher Nolan wouldn’t miss a chance to save Inception and other of his works.

But I was dismayed to learn that a great many companies, taking advantage of a loose requirement about what counts as a deposit copy, are submitting DVDs, Blu-rays, and even DVD-R versions of their films. If they can’t submit a print, they should at least provide an unencrypted DCP. Otherwise, scholars and audiences of the future will encounter the digital equivalent [18]of the crawling, scraped deterioration we see with film.

101 movies

Fortunately for me, 1910s films are still available on film. Viewing prints of films stored at Culpeper are shipped to the James Madison Building in the District. There, in the Moving Image Research Center, they may be viewed on my old friend, the flatbed machine known as a Steenbeck. Every day a Steenbeck patiently awaited my depredations.

The staff of the Reading Room were just superb in helping me order titles and dig up information about them. Above you see the team I worked with: Dorinda Hartmann, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-Johnston, and Zoran Sinobad.

I learned an enormous amount from them, and I enjoyed talking movies with them during our breaks. Others who helped me greatly were Karen Fishman, Research Center Supervisor, MBRS Division; Alan Gevinson, curator of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting; and David Pierce, Assistant Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus.

My mission was to see as many American fiction features from the 1910s as I could. This was the period when a five-reel film (ca. 60-70 min.) became a dominant format, though shorts and longer films were also being made. I’ve spent about a decade watching largely European films of the period in various archives and in Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, with results I’ve occasionally discussed on this blog. A visit to the LoC nicely complemented my Continental and Nordic explorations. Although several American films from the period are available on DVD, I’ve tried to see even those in film copies. (Why? Tell you later.)

For a time I was joined by James Cutting, perceptual psychologist extraordinaire, who enthusiastically wanted to watch these old movies. His presence helped me a lot, sharpening my attention to things in the images. Here’s James, skewed, during our nighttime trip to Chinatown for food and Get Out.

In all, across 42 business days (had to take days off for holidays and inauguration), I saw 101 films, 98 from my period and three others for other projects.

Not all the films survive complete. Some lacked one or more reels. That’s a great pity in the case of Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s False Colours (1914), Sunshine Molly (1915), and Idle Wives (1916); William deMille’s The Sowers (1916); William Desmond Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916); and many other stunning projects I got a glimpse of. But a little is better than nothing, as I’ve tried to show in an earlier entry [21] and hope to show in later ones.

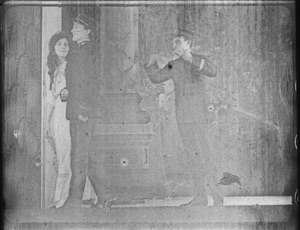

A few portions that remained were plagued by deterioration. Usually, that consists of ameba-like creatures swarming over the image. Some decadents wallow in these miasmas, especially on tinted prints. (See Lyrical Nitrate [22] and Decasia [23].) Me, I can’t romanticize turning a 1910s drama or comedy into a 1960s abstract film. I want to see the story and the style, dammit.

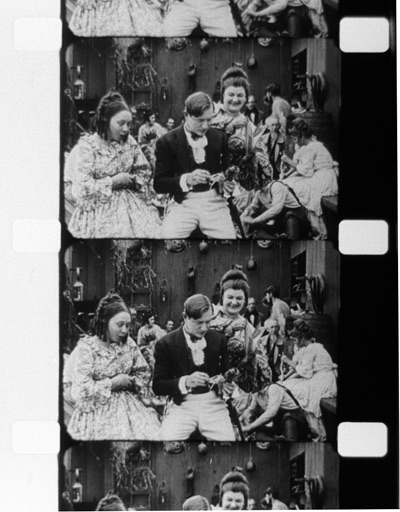

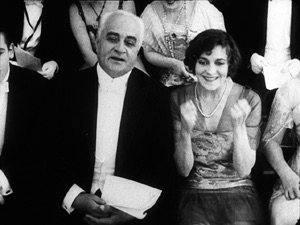

Another form of deterioration yields a ghostly, scraped-off image. Sometimes the decay changes from shot to shot, presumably because at some points the shots were segregated for tinting and toning. Here’s The Caprices of Kitty (Smalley, 1915), with Elsie Janis watching a play. In a gag on celebrity, she’s also an actor on stage (and in drag). After the nice shot of her and her father in the audience, the stage shot makes you shudder.

A first effort to clean it up with Photoshop helps, but still…Makes you remember why all that effort on the Packard Campus is necessary.

Of course a great many copies I watched were gorgeous. Orthochromatic film, with a ton of light dumped on the sets, yields images with incredibly rich gray scales. (My Ilford photochemical black and white couldn’t capture that range.) When we saw this parlor shot from By Right of Purchase, a 1918 Norma Talmadge melodrama, James blurted out, “Clutter!” A connoisseur of dense images, James later ran it through his algorithms and found that it had a spectacular degree of clutter.

Filigreed clutter is another big reason to like the 1910s, and archives like the LoC team are keeping it visible for us.

Deterioration isn’t the only insult these movies suffer. There’s the degradation of them in oft-copied versions. Compare this shot, from Reginald Barker’s splendid William S. Hart film The Bargain (1914), with the image you get if you buy the bootleg DVD.

Shot scale changes because of video cropping, facial expressions become unreadable, the eyes go dark, and that mounted trophy in the back just disappears. Of course things go a lot better with a video version of a film restored by the Culpeper crew (Moving Image Curator Rob Stone in particular). Olive Films has just released Wagon Tracks (1919), a fine William S. Hart film, on a very pretty Blu-ray [31] derived from a tinted Library of Congress restoration.

So it can be done well, though I still prefer to study a 35 print, preferably untinted. Call me cranky.

The Packard Campus visit brought home to me how much effort is spent saving our film heritage. That heritage includes films that are little-known, but deserve better recognition. Watching with me, astonished by the technical ingenuity and wide-ranging experimentation rushing past us, James was reminded of the Cambrian Explosion [34], that period of origin and rapid diversification among earthly organisms.

It’s an intriguing analogy. A mere dozen years yielded “our cinema,” as I’ve argued in this video lecture [35]–the sturdy prototypes of moviemaking today. Yet along with enduring models of story and style came a cascade of ingenious novelties that weren’t taken up much. The 1920s, for all their innovations, tended to prune away some of the more eccentric but intriguing tendencies that burst out in the 1910s. In my next entry on the subject, I’ll offer some examples.

I owe a tremendous debt to the John W. Kluge Center for supporting my stay at the Library of Congress. Thanks especially to Ted Widmer, Director of the Center, and his colleagues Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello. Also I enjoyed enlightening conversations with Peter Brooks, in residency at the Center, and the other Kluge Chairs Timothy Breen, Jose Casanova, and Wayne Wiegand, all embarked on fascinating projects.

Thanks also to all the staff at the Packard Campus, who enthusiastically shared information about their work habits. We’re grateful to Greg and Mike for spending so much time with us.

The digital spoor on the Packard Campus leads far and wide; a Google search will yield you many nifty items. The 2007 plans for the facility are reviewed in this information-packed presentation [36] by Greg Lukow. For something more recent, try the Wired visit [37] by Brian Gardiner. On the digitizing side, see Boing Boing’s extensive coverage [38], including an interview with Greg. There’s a good half-hour C-span documentary tour [39] led by Mike Mashon. Mike’s blog Now See Hear! [37]offers updates on current Campus events.

Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait [40] (McFarland, 2000) remains the essential source on U.S. film preservation. It has some good anecdotes about Kemp Niver, including one involving a pistol and Raymond Rohauer. Criterion has a nifty little film [41] on wet-gate restoration of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935).

If you’re interested in film research, you need to read James Cutting’s sweeping big-data studies on film. A good summing up of part of it is “Narrative Theory and the Dynamics of Popular Movies.” [42] There’s interesting commentary on it here from a psychologist [43] and here from a screenwriter [44] (who clings to the three-act model). James’s book on the formation of the canon of Impressionist painting [45]has been invoked in Derek Thompson’s book Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction [46] (Penguin, 2017), 23-26.

For more on visual clutter, see this paper on clutter and visual search [47], of which Tim Smith [48], master of eye movements [49], is a co-author; and two papers specifically on movies, by James, one with Kacie Armstrong: here [50] and here [51].

DB makes Lillian bashful in The Lily and the Rose (1915).