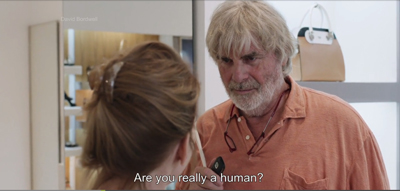

Graduation (Cristian Mungiu, 2016).

DB here:

More from this year’s Vancouver Film Fest [2], abundant as ever (over 200 features, over 300 films in all).

Comedy, Chaplin supposedly said, is life in long-shot, while tragedy is life in close-up. This is questionable on its face, but put that aside. What about medium shots? Maybe they’re either comic or tragic? Or maybe just neutral? Any shot framing the body from, say, the waist up to the head is the workhorse of most film traditions, and it’s ready to be recruited for almost any purpose.

I was led to think about this handy tool when watching two strong and enjoyable films, Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation and Maren Ade’s Tony Erdmann. Both directors made some similar artistic choices, such as that slightly swaying handheld framing that seems de rigueur in many films nowadays–the “free camera,” as the Danes call it [3]. But the two films show different ways of exploiting the medium-shot of people talking. The differences, I think, depend on both genre factors and one crucially diverging choice.

Screwball comedy with a German accent

Toni Erdmann updates screwball comedy: a mischievous madcap disrupts the staid life of an uptight character s/he loves. In classic Hollywood the madcap might be a wild woman (Bringing Up Baby) or a free-spirited man (Holiday), with romantic union the result. The variation here is that the madcap is a father. Winfried tries through pranks and impersonation to loosen up his rigid daughter Ines, who’s striving to be a cool corporate barracuda.

The plot is a series of encounters in Ines’ high-stress professional life. Her rounds of meetings and cocktail parties are constantly invaded by the bulky Winfried. Sometimes he’s his unkempt self (often adorned with splayed monster teeth), sometimes he’s a fake businessman/diplomat named Toni Erdmann. When father shows up, she’s mortified. She resorts to the classic strategies of the screwball target: flight, pretending not to know him, and desperately going along with the masquerade in hope that it will pass. Finally Winfried breaks down her defenses, and we get the obligatory scenes when the by-the-book character finally lets loose (here, through a heartfelt song and later by a creative effort at party hostessing).

The premise of screwball is a bit of a Jonsonian power trip. We’re asked to sympathize with people who have enough leisure and money to punk everyone around them. The cruelty of the put-on, with trusting characters gulled by free spirits, is built into the genre. In Toni Erdmann we have to be ready to accept not only the deflation of a CEO, which is always fun, but also the terrorization of working stiffs like delivery men and mechanics. To the film’s credit, there is a moment when Winfried learns the price that others must pay for a retiree’s cute mischief. Along the way is some sharp satire on corporate predation and its fashions in “coaching” and “team-building.”

All this is played out in good old medium shots. And those in turn are embedded in good old shot/ reverse-shot.

Toni Erdmann relies on shot/reverse-shot technique primarily, I think, because of the need to show reaction shots. A good part of comedy is reaction, and camera ubiquity allows us to watch the gag and the payoff in a tick-tock editing rhythm. Ade can time people’s responses to Winfried’s sinister leer in ways that maximize the laugh.

Shot/ reverse-shot has of course long been a mainstay of classical Hollywood continuity style, partly because it mimics the flow of turn-taking in conversation. Like side-participants in a real-life situation, we shift our attention from speaker to speaker, thanks to the cuts.

Over-the-shoulder framings help anchor us in the space of the scene, so we always know where we are.

Assisting that sense of stability is the so-called 180-degree system of staging, shooting, and cutting. This keeps all the eyelines, postures, and backgrounds fairly consistent. At several points, though, Ade’s reverse angles “break the line,” shifting us across the axis of action. This creates what’s been called “200-degree-plus” staging and shooting.

Fortunately, our pragmatic sense of who’s talking to (or looking at) whom overrides the slight jump. The shift can be smoothed if there’s a strong cue–as here, when Winfried turns his head from the courier on his doorstep.

When you have several characters present, and you’re willing to break the 180-degree line in your reverse shots, you can cheat positions from shot to shot in remarkable ways. A cut can magically delete a character for the sake of emphasizing another one’s reaction.

For example, at a fancy party, Winfried-as-Toni approaches a woman and claims he works at the German embassy. The first shot favors the woman, her friend, and a nervous Ines, who tries to pull Toni away.

But when we cut to a reverse of Toni, Ines is no longer beside the blonde woman.

She has been shifted to the left–in fact, moved completely offscreen–in order to supply a clear view of Toni. His sharp glance to the left confirms her position.

Cheating shot/ reverse-shot positions is a common tactic of classic continuity filmmaking, and Ade uses it freely. The more characters who crowd in, the more chance to cheat them. In some shots during the big party, Ines is close beside her boyfriend as her boss greets Toni. But in the 180-degree reverse angles the couple gets spread out, with the man pushed offscreen entirely, before a new setup brings them back–and deletes the boss.

It’s remarkable how little we notice these shot-to-shot disparities as long as positions are grossly consistent, and as long as we’re given other things to pay attention to. (Dan Levin [19] has studied filmic “change blindness” experimentally.)

Throughout, Ade’s cutting and camera placement help us enjoy, moment by moment, the shocked, bewildered, and bemused responses to Winfried/Toni’s campaign to humanize Ines.

The case of the missing reverse shot

Change the genre from comedy to drama, though, and minimize editing, and you get something else. You get, for instance, Graduation (Bacalaureat).

Mungiu traces a few tense days in the life of Romeo, a provincial doctor living in a bleak housing flat. His daughter is promised a scholarship if she does brilliant exams, but before she can take the first test she’s assaulted and the trauma threatens to wreck her performance. To protect her, Romeo uses his network of friends to arrange for favorable grades. The scheme precipitates crises with the daughter, her boyfriend, Romeo’s wife, his mistress, and a mysterious attacker.

The film is essentially a set of two-handed dialogues, tracing how the pressure on Romeo builds from day to day and hour to hour. These encounters are filmed mostly in medium shots, as in Toni Erdmann, but with one essential difference. The shots are long takes, and they’re kept fairly stationary—that is, no circling or panning of the camera. Handling some scenes in just a single shot, Mungiu often avoids the shot/reverse-shot cutting we see in Ade’s film.

This choice might seem akin to the virtuoso long takes of Iñárritu in Birdman. But as I tried to show back when [21], Iñárritu’s long takes actually mimic the patterns and effects of shot/reverse-shot editing. In Birdman, we’re denied nothing because the moving camera always picks up the reaction that would normally be captured in a reverse-angle cut. By contrast, Mungiu doesn’t give us the long-take equivalent of continuity editing; he denies us reaction shots quite stringently.

In The Graduation, characters tend to interact in in lengthy profiled two-shots, not 3/4 reverse angles.

This framing gives us some access to the characters’ emotions. It’s worth mentioning, though, that profile shots aren’t strongly informative about a person’s facial expression. A frown or a smile is more “readable” in the 3/4 framing favored by reverse-angle cuts.

More remarkable, though, are those passages in which Mungiu simply denies us access to Romeo’s facial expressions by pivoting him away from us and denying a reverse shot.

Actors have turned their backs to the audience for a long time in both theatre and film, usually to enhance a gesture, to call attention to another actor, or to delay the revelation of the face. But since the reverse-angle cut is such an ingrained convention, we count on camera ubiquity; we expect to see everything. When characters have their backs to the camera, and the director doesn’t cut to an angle that reveals their reactions, this choice can have powerful narrative effects. It can make the character’s psychology more opaque and mysterious. It can also build suspense as we wait for some clues (in words or gestures) to the character’s response.

The withheld reverse angle, within longish takes, was a prominent tactic in Antonioni’s 1960s style, as in L’Avventura.

Mungiu isn’t quite so flagrant, favoring 3/4 rear view like the over-the-shoulder view of orthodox shot/reverse shots. This will do duty for orthodox POV cutting: We see what Romeo sees but not exactly through his eyes.

The result is to attach us to the protagonist but not in a deeply subjective way, as Hitchcock might with intense optical POV shots. These shots might suggest a perceptual subjectivity–we see what Romeo sees, more or less–we don’t know how he’s reacting. Sometimes, as when he and a colleague inspect an X-ray, we get almost no sense of the reaction, or what they’re reacting to.

In addition, Romeo is a fairly phlegmatic man anyhow; he’s hard to read even facing front.

His failed ambitions and troubled relation to his wife, as well as the mess he’s making of the exam scheme, seem to have given him a fixed, furrowed anxiety. I doubt that even Toni Erdmann could make him smile.

Still, most directors would probably have filmed Romeo driving his daughter to school, from an angle in front of the car, shooting through the windshield. And most directors would have revealed something of his response when, as his scheme unravels, the school principal orders him not to contact him again or come near his house.

Even more striking, at a climactic moment, he’s questioned by two policemen. I don’t have an illustration for you, but we’re perched over his shoulder and watch the two cops–not unsympathetic–explain to him at length the punishment likely headed toward him. We get no chance to see whether his facade cracks even a little. But observing him so often as a solid lump in the foreground or on the edge of the shot gives him, I think, a sort of obdurate resistance that suggests he will resist what’s coming. In these grim circumstances, stubborn stolidity gains a heroic quality.

Other characters, notably his wife and daughter, get framed in ways that allow us to track their emotions. It seems somewhat ironic that the sunniest, most straightforward and untroubled faces we see are those of the class lined up for the graduation picture.

No surprises here. The head-and-shoulders shot gets a lot of its impact from its coordination with other stylistic choices: the decision to cut (or not to cut), the selection of the angle (frontal, or from behind), and the overall tone of the film (grim or light-hearted). There are no general rules. Contra Chaplin, the close-up can be comic, as in Harold Lloyd. The long-shot can be tragic, as in Hou Hsiao-hsien [37] or Edward Yang [38] or Theo Angelopoulos [39]. As with these shot scales, the workhorse medium shot is coordinated with other techniques to achieve its results in different contexts.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Entertainment for their generous help in preparing this entry. Toni Erdmann [40] is scheduled for U. S. release by Sony for 25 December. Graduation is distributed by IFC in the Sundance Selects collection [41]; no U. S. release date yet announced.

I discuss the blend of cinematic convention and social intelligence elicited by shot/reverse-shot techniques in the essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” in Poetics of Cinema, 57-82. On the quick information pickup involved in certain facial views, see Vicki Bruce, Tim Valentine, and Alan Baddeley, “The Basis of the 3/4 View Advantage in Face Recognition,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 109–10; and Robert H. Logie, Alan D. Baddeley, and Muriel M. Woodhead, “Face Recognition, Pose, and Ecological Validity,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 1 (1987): 53–69.

On the 200-degree-plus style in modern film and television, see The Way Hollywood Tells It, 177-179. On change blindness, an earlier blog entry is here [42]. Another entry bearing on the matter, also VIFF-inspired, is “Where did the two-shot go? Here.” [43]

The laconic rear-view shot became a common tactic of modernist cinema. For other examples, you can see this entry on Béla Tarr [44]. But Mizoguchi got there [45] quite a bit earlier.

Toni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016).