DB here:

There have long been film collectors, and they’re central to film preservation. Some archives, notably the Cinémathèque Française and George Eastman House, were built on the private hoardings of passionate cinephiles. Filmmaking companies, both American and overseas, had little concern for saving their films until home video showed that there was perpetual life in their libraries. By then, many classics had been dumped, burned, or left to rot, and in many cases collectors came to the rescue.

In America, private collecting really took off after World War II. What happened afterward is too little known among cinephiles, but it represents an important part of film culture. A new book [3] fills in a lot of the detail, and in a very entertaining way. It’s a big contribution to our knowledge of the afterlife of the movies.

16 + 35 = $$$$

In the late 1940s, 16mm versions of theatrical releases became widely available. For a while the studios contemplated replacing 3 5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

Many of those firms dealt in foreign titles, which weren’t as attractive to most collectors—who were in love with Gollywood. For them, the floodgates had already opened when the studios licensed their pre-1948 product to television. The 1950s and 1960s were very unlike the multi-channel 24/7 TV environment of today. The networks didn’t fill the broadcast day, and many independent stations tried to support themselves apart from the nets. So everybody needed what we now call content. Our colleague Eric Hoyt [4] has traced in detail how C & C Movietime and other entrepreneurs bought rights to classics and not-so-classics and packaged them in 16mm bundles for local TV stations. Those prints were shown throughout the day and night, interspersed with commercials cut in by staff like Barry C. Allen [5].

In the 1950s hundreds of copies of film classics were abroad in the land. But many of these TV prints wound up discarded and scavenged by guys (almost always guys) who wanted to show them at home. Aficionados started building their own libraries.

Collecting 35 was tougher, but it could be done. Older films were stored in labs and depots. They might wind up in Dumpsters or be smuggled out by enterprising employees. Of course showing 35 was more difficult, but it wasn’t impossible to get 35 projectors fairly cheap, and if the hobbyist was willing to make major home renovations, he (again, almost always a he) could set up a personal screening room. Some went with curtains, masking, auditorium seats, popcorn machines, and other amenities. The idea of “home theatres” for ordinary folks has its origin here.

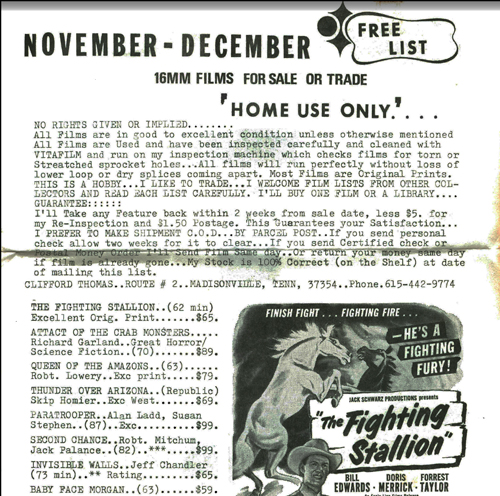

Acquiring 16mm was gray-market but ultimately not very criminal. Because of the First Sale Doctrine [6], a collector was not in violation if he bought a 16 print that had already been sold (to a TV station). If I buy the new Carl Hiaasen novel Razor Girl [7], I can sell my copy to you because someone sold it to me. What got 16mm dealers in real trouble was their zeal to copy prints. If they got access to a nice 35, they might make a 16 reduction; or if they had a decent 16, they might pull dupes. These were definitely illegal, as if I were to scan Razor Girl and sell you a pdf.

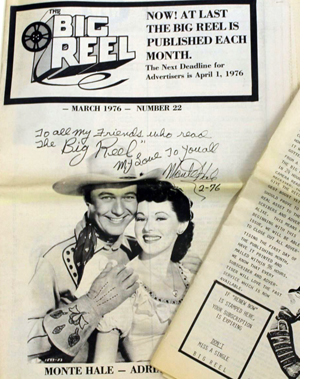

[8]Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

[8]Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

With some exceptions, 35 prints weren’t originally sold, only rented, and so possession of one suggested, to suspicious minds, big-time theft. Actually, most collectors’ prints had been junked, and you can argue that once something is tossed out, it’s the American Way to scavenge and recycle it.

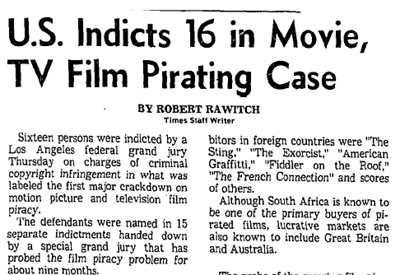

Beyond the domestic collectors’ market, there was money to be made with 35 prints. American films didn’t circulate much in Cuba, South Africa, parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe, so there was an international demand for bootleg copies, and some dealers were happy to meet it. I lost out on a collection of Hong Kong films that was bought by an Indian dealer who intended to circulate them at home. I always think of that episode when I see the almost inevitable kung-fu fight in an Indian action movie.

The sale of 35 boomed because of another factor. With the rise of the blockbuster mentality in 1970s-1980s Hollywood, the nation was awash in theatrical prints. Then as now, a film might open on thousands of multiplex screens, play a few weeks, and be done. The studio would keep a few of those prints, but the rest would have to be disposed of. Salvage companies were contracted to destroy them, but—human nature being what it is—often some copies slipped out and into eager hands.

Films stored in laboratories or warehouses had a habit of disappearing as well, and prints shipped to theatres might be waylaid. I remember booking Blue Velvet and learning that the copy had disappeared in transit. The fact that prints were labeled with their titles printed in large letters probably didn’t help keep them safe. I was always startled to see the casual ways in which prints were handled. On Thursday midnights I’d leave a screening at one local theatre and see, neatly lined up on the sidewalk, shipping cases bearing the titles of films that had played there in recent weeks, waiting for a UPS pickup the next morning. After a theatrical run, exhibitors cared as little for prints as producers and distributors did.

Many collectors favored older titles, but others were as susceptible to blockbuster mania as general audiences. Star Wars, Jaws, The Godfather, and all the other top hits became as sought-after as Casablanca and Snow White. Collectors still boast of having multitrack, IB-Tech copies of 1970s and 1980s franchise pictures.

Enter the Feds

Los Angeles Times (17 January 1975), B1.

I’ve moved from describing the collectors’ market to describing the dealers’ market. That’s because they were almost one and the same. Collectors needed dealers to help find the rarities they yearned for; collectors started to deal to support their habit; and dealers, whether collectors or not, found that they could make money acquiring and selling movies. Demand and supply, in solid capitalist fashion, created an underworld traffic in prints.

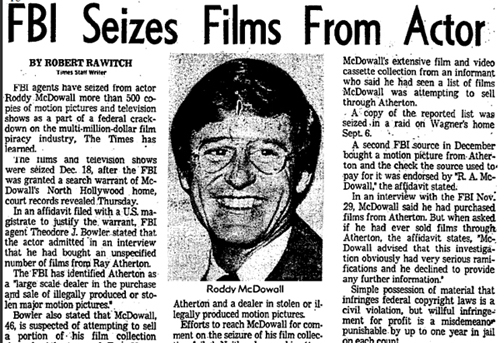

The studios didn’t take this lying down. With the aid of the FBI, they pursued collectors, pressuring them to snitch on their suppliers and fellow addicts. Former child star Roddy McDowall, an avid collector, was the most visible target of these maneuvers. I well remember the chill that passed through the collector community at the news of the Feds’ raid on his house, which turned up hundreds of prints and videos. McDowall, who could probably have won a legal case, gave up many of his contacts. Charges against him were dismissed, but the U.S. Attorney pursuing the case warned that the activities of film collectors (said to number 65,000) “could constitute serious violations of both state and federal law.”

Most collectors flew under the radar, though. Although McDowall’s collection was mostly 16mm, the studios turned a blind eye to 16mm collectors. Famously, William K. Everson helped studios uncover lost films (e.g., obscure Fords and Stroheims) and as payment received 16mm copies of his discoveries. Collectors like Bill, who accumulated several thousand prints, shared their libraries with archives and film schools; at NYU, Bill taught from his collection for many years.

Home video didn’t destroy this underworld right away. The first video systems were of such poor quality that they couldn’t compete with 16mm projection, let alone 35. However, as formats improved in the 1990s, more and more collectors turned to video. Why thread up a battered copy of an MGM musical when a pretty nice DVD could just be popped into your player? With the arrival of Blu-ray, which can look very impressive projected in theatrical conditions, 35 began to be seen as more and more a retro hobby. And your average hobbyist was discovering that he (still almost certainly a he) was aging. Or dying.

The studios mostly lost interest in film-based piracy, once video presented a threat on a much bigger scale. Duplicating VHS and laserdisc, always imperfect, was followed by the cloning of perfect copies of DVDs. Now, of course, the main arena is the Net, where film piracy via BitTorrent has exploded to a level the old-timers couldn’t imagine. Back in the 60s, there were very few film collectors. Now, thanks to digital convergence and massive hard drives, everybody is a film collector—not only he’s.

Boom and busts

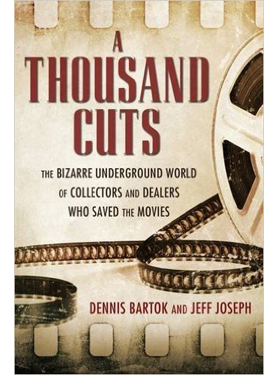

This is the world chronicled, with affection, humor, gossipy detail, and a pang of melancholy, in Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph’s A Thousand Cuts [3]. Dennis has been head of programming for the American Cinematheque [11], and he currently heads the distribution company Cinelicious Pics [12]. Jeff was one of the top film dealers in the country; at its peak, his company SabuCat [13] sold about 1,000 prints per month. In the wake of the McDowall bust, Jeff became the only film dealer to serve time for selling prints. Jeff is now a distinguished archivist, conserving 3-D prints [13] and, most recently, rare Laurel and Hardy movies [14].

The book lives up to its subtitle: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies. Through interviews, documents, and vast knowledge of the world of film dealing, Bartok and Joseph have given us an invaluable survey of a wondrous land. It’s as gripping, and sometimes as hallucinatory, as any Forties B noir.

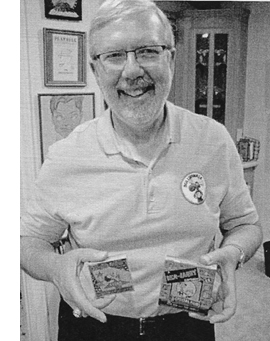

[15]Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

[15]Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Once we leave behind the celebrities, things take a more exotic turn. There’s Evan H. Foreman, the first collector targeted by the studios, a tough customer who fought for the right to sell prints and was called to testify before a Senate committee. There’s Ken Kramer, proprietor of The Clip Joint, a Burbank archive and screening facility decorated with posters and Christmas lights. There’s Tony Turano, who claimed for years that he was the baby in the bulrushes in The Ten Commandments. Tony kept his apartment heavily curtained, the better to preserve Claudette Colbert’s headdress and robe from Cleopatra (1934). Paul Rayton, projectionist extraordinaire, stores the cans for his rare Oklahoma! print in the back seat of his car. Not the film–it went vinegar long ago. Just the cans.

There’s Al Beardsley, uniformly considered untrustworthy, perhaps because he simply picked up a 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia posing as a delivery courier and immediately sold it to a collector. Beardsley gave up film dealing for sports memorabilia, and became a participant in the O. J. Simpson throwdown in Vegas. As Beardsley recalls his encounter with one Thomas Riccio, who had set up the O. J. meet: “I had a drink and, I believe, a hamburger that Riccio paid for. He feeds you before he screws you.” O. J. was more direct: “Motherfucker, you think you can steal my shit and sell it?” Yes, firearms were involved.

This is as wild and crazy as any nerd culture can be. Like collectors of comic books and LPs, film mavens are clannish and wily, generous and secretive, boastful and yet somewhat innocent. These guys can’t be considered Geek Chic; they retain an unselfconscious love for what moved them in their youth. They live in the Adolescent Window [16], as we all do, but they don’t pretend to have become hip. And they run risks that other collectors don’t. A book or record collector runs no risk of arrest. But should a film collector offer a rarity to an archive? Will the studio claim it and bury it? Will the law get involved? Paranoia strikes deep, and justifiably.

Some of the tales are painfully funny, some just painful. This is the sort of book that contains sentences like:

The two were briefly partners as film dealers in the early 1970s, until Ken’s then-wife Lauren left him to marry Jeff, shortly after they were discovered having an affair at the 3rd Annual Witchcraft and Sorcery Convention.

Turano, wheelchair bound, had a habit of bursting into showtunes at the top of his voice. Tom Dunnahoo, of Thunderbird films, “routinely passed out on the floor of his film lab drunk on Drambuie.” A dealer takes pride in the fact that at his trial, the expert on the stand couldn’t tell his dupe of Paper Moon from the original. Another bit of dialogue:

“You remember I had a beet-red print of Giant? Well, Louie Federici ran it and borrowed a beautiful IB print of Giant. Afterward he sent it back to Warners, and you know what they got? A beet red print,” he says, face lighting up.

“You swapped it out?” Jeff asks.

“I did. And later I traded it to you for Singin’ in the Rain. How about that, huh?”

Nearly every page of my copy boasts my penciled ! in the margin.

Saving the movies

Jeff Joseph and Dennis Bartok, Cinecon 2016.

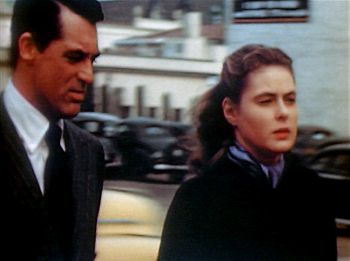

The book stresses that collectors functioned as preservationists. Just as in the early days of archives, they have saved films major and minor from destruction. Just last week, we learned that a collection of 9.5mm has added more footage to a partially surviving Ozu film [19], A Straightforward Boy. Famously, missing King Kong footage was discovered by a collector. . . and given, not sold, back to the studio. Tony Turano found a missing Fred Astaire number from Second Chorus in Hermes Pan’s closet. Jeff Joseph preserved color behind-the-scenes footage of Animal Crackers and found remarkable home-movie Kodachrome footage of Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant out for a walk during the shooting of Notorious (surmounting today’s entry). Mike Hyatt has devoted his life to cleaning up The Day of the Triffids. Using a jeweler’s loupe and a needle, across many years, he flicked over 20,000 bits of dirt out of the camera negative.

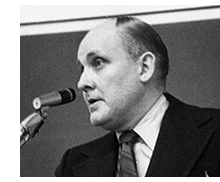

[20]Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

[20]Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Most of the stories in the book come from the West Coast, as you’d expect. Other regions have their own lore and characters. The East Coast was a lively scene, centering on Manhattan’s Theodore Huff Film Society (duly noted in A Thousand Cuts) and Bill Everson’s screenings at the New School and elsewhere. Scorsese is, of course, a famous collector. Until this last year hard-core fans of old films gathered at Syracuse’s fine Cinefest [21]. The Midwest had its own center of film trade, Festival Films [22] in Minneapolis, now a source of public-domain items. The screening-and-dealing gathering Cinevent [23], in Columbus, Ohio, is entering its 49th year.

There were colorful personalities hereabouts too, including a Milwaukee collector with a stupendous array of original Hitchcocks from the 1950s. Another Wisconsin collector, Al Dettlaff [24], discovered and jealously guarded Edison’s 1910 version of Frankenstein. I met a collector in remote Minnesota who had converted his garage for 35mm screening both indoors and outdoors. He could aim his projectors to shoot out onto the back yard for neighborhood shows (a popular pastime for collectors). During the snowbound winters, he could swivel the machines to shoot through the kitchen to the living room. I asked how his wife felt about sawing holes in the walls. He said: “She’s fine with it. She knows I can get a new wife a hell of a lot easier than an IB Tech of Bambi.”

Dennis and Jeff are to be thanked for recording precious information about a phase of American film culture that has been neglected. They’re continuing the effort with a clip show on 23 September [25] at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre. It will include many items mentioned here, as well as a Bela Lugosi interview from 1931.

The collecting adventure is not quite over. The book profiles passionate younger aficionados, some of whom keep the energy going online. Still, as someone who has relinquished his passion for owning film on film and is happy that archives are taking over the task, I’m afraid it’s evident that the curtain is coming down. Without collectors, who will scavenge all the films not likely to be transferred to digital formats? The book ends with a list of six interviewees who died during writing and publication. And in the podcast below, Jeff glumly notes that studios are still junking prints.

Thanks to Jeff Joseph for illustrations. The Len Maltin picture is by Dennis Bartok. For a fascinating podcast that gives the authors a chance to expand on many aspects of A Thousand Cuts, check The Projection Booth [26]. There’s a shorter streaming interview at KPCC radio [27].

Typical collector story: How did William K. Everson acquire his K? He told us that the first movie he remembered seeing was by William K. Howard, so Bill borrowed the middle initial. Another: We did our bit. After seeing an ad in The Big Reel for a hand-tinted Méliès print, we alerted Paolo Cherchi Usai, then at Eastman House. It turned out to be one of the lost Méliès titles.

Thanks to Haden Guest for tipping me to the Ozu rediscovery. I talk about how piracy created a classic here [28]. For more on 16mm collecting and showing, go here [29] and here [30]. In this entry [31]we cover Joe Dante’s remarkable visit to Madison and his presentation of The Movie Orgy, one result of his insatiable collecting appetites.

P.S. 14 September 2016: I should have mentioned another collector committed to preserving 3D films. Since 1980 Bob Furmanek has been building a large 3D archive, a project that is still ongoing. The history of his work is traced on his site [32].

P.S. 15 September 2016: Thanks to Christoph Michel for correcting a howler that out of shame I shall not name.

Animal Crackers, Multicolor on-set record (1930). Courtesy Jeff Joseph.