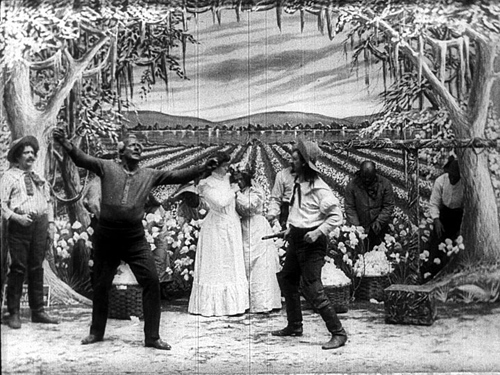

Ma l’amor mio non muore! (aka Love Everlasting, 1913). Lyda Borelli.

DB here:

The core of cinematic expression is editing. Since the 1920s, that view has been part of the lore of film aesthetics. Editing, people said, is what distinguishes film from other media. After all, the single shot is both a picture (like a painting) and a dramatization (like a scene in a stage play). But put one shot with another and you’ve got a technique impossible to parallel in other media.

But if we look closely, we find that the film image is as “uniquely cinematic” as editing. After all, a film is an image, but it’s a moving image, which is sharply different from a painting. And although a shot is a dramatization, it’s two-dimensional (unlike a stage scene) and the space it captures is quite different from that of the theatre [2]. Anyhow, maybe editing isn’t uniquely cinematic. Comic strips juxtapose discrete images, and some forms of theatre (such as pageants, or turntable stages) can shift rapidly between scenes. Once we start to compare adjacent media, we find many overlaps in their expressive resources.

Why did early film theorists make editing so important? They were often defending the view that film was a new art, in the teeth of opponents who claimed that it was simply photographed theatre. Accordingly, film’s defenders looked for features of films that seemed to have no counterpart in theatre, such as the close-up and, more pervasively, editing.

Since then, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of film’s artistic capabilities. Filmmakers, particularly those in the early sound era (Renoir, Ophuls, Dreyer, Mizoguchi), showed the expressive power of the single shot. This tendency was amplified in the 1950s and 1960s with Antonioni, Jancso, Andy Warhol, and many other directors. Now nobody blinks if a filmmaker like Hou [3] or Yang [4] presents a lengthy, unedited sequence.

Informed by what’s possible in the single shot, we ought to find the earliest filmmakers using the resources of staging, composition, and performance in felicitous ways. So we do. Once we foreswear the cult of the cut, we can see that early cinema made extensive use of cinematography and mise-en-scene for powerful artistic effects. And conceding that, we suddenly find ourselves back in the lap of the other arts–painting and theatre.

Living pictures

[5]No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

[5]No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

Here’s the authors’ statement of the book’s argument:

While previous accounts of the relationship between cinema and theatre have tended to assume that early filmmakers had to break away from the stage in order to establish a specific aesthetic for the new medium, Theatre to Cinema argues that the cinema turned to the pictorial, spectacular tradition of the theatre in the 1910s to establish a model for feature filmmaking. The book traces this influence in the adaptation and transformation of the theatrical tableau, acting styles, and staging techniques, examining such films as Caserini’s Ma ľamor mio non muore!, Tourneur’s Alias Jimmy Valentine and The Whip, Sjöström’s Ingmarssönerna, and various adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

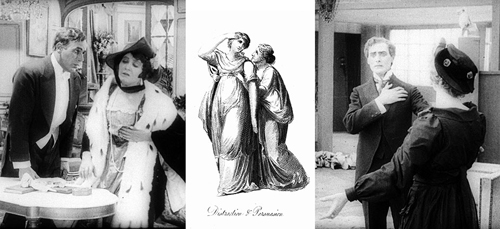

The twist here is that turn-of-the-century artistic culture had already blurred the boundaries between theatre and painting. Painters drew upon the stock gestures and poses of the stage, while plays presented vivid visual effects that were indebted to painting. The term “tableau,” referring at once to a picture and a poised stage image, captures this convergence between the media. That’s why Ben and Lea refer to “stage pictorialism” as the nexus of their inquiry.

Thanks to their research, we can see the unbroken long- or medium-shot of early features as permitting a complex choreography of facial expressions and bodily attitudes, which were in turn indebted to both pictorial and dramatic traditions. Standard gestures were summoned up and reworked to suit dramatic situations–as, for example, clutching.

When we do find editing or camera movements in these films, they’re often at the service of the performance style. Ben and Lea powerfully make the case that the expressive human body was at the center of storytelling in the first years of silent cinema. (If nothing else, the book is an in-depth analysis of diva acting from the likes of Lyda Borelli and Asta Nielsen.) By studying the history of theatre, we can learn to appreciate aspects of acting that might otherwise escape our notice.

Theatre to cinema to pixels

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Slavery Days (Edison, 1903).

How, you’re asking, can you gain access to the ideas and information and images in this fine book? It’s now criminally easy.

When Theatre to Cinema was published, all the illustrations came from 35mm film prints. Those originals were gorgeous. But in some printings of the book the stills came out badly, and when the book moved to print-on-demand status, the images suffered even more. A couple years ago, Ben and Lea rescued their book and took the opportunity to make a digital version. It’s unrevised, largely because updating a twenty-year-old volume would be a major overhaul, but errors have been corrected and–very important–the stills have been much improved.

Start here, [7] with the introduction to the project. You can download the new edition of the whole book, section by section, here [8].

Naturally, Kristin and I are sympathetic to this effort. Since we started our website back in 2000, we have explored ways to amplify and extend our ideas by means of the web. In the beginning, and inspired by Philip Steadman’s Net-based supplements [9] to his excellent Vermeer’s Camera [10], I added material [11] that would enhance arguments I made in Figures Traced in Light. Then we set up our blog, now in its tenth year. Over the same period, we posted web essays, as you can see in serried ranks page left. We also used the site to preserve older material, such as film analyses [12] dropped from editions of Film Art: An Introduction and even entire books, as in Kristin’s 1985 monograph Exporting Entertainment [13]. We’ve mounted video lectures [14]. And we’ve produced a new edition of an older book, Planet Hong Kong 2.0 [15], and original e-books such as Pandora’s Digital Box [16] and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages [17].

Ben and Lea have found another way to expand a book’s Web life. They have put Theatre to Cinema at the heart of a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries. Here’s what they offer:

In this collection, we try to supplement the description and illustration that accompanied the book in a way that makes it easier for readers to appropriate our work—both to understand it, and to make use of it in research and teaching. What were illustrations in the pages of the book are also presented here as better-quality downloadable images.

For example, [18] you can pick a still, find its mates in a single display, and blow it up for scrutiny. If you want import it into your own files, you may choose among four different file sizes.

The provenance of each still is provided, so scholars can compare prints from different sources. In addition, there’s a master index [20] of the visual documentation, in sequential groupings across the book.

Finally, Ben and Lea plan to add video extracts from some of the films they discuss. When those go up, we’ll announce it here.

Every admirer of silent film, and everyone who studies the interrelationship of the arts, should read this book. Hard copies are still being sold online [21], but they’re apt to be versions with weakly reproduced stills. Get one if you want, because a book is a good object to have in hand. In addition, for free, you can own a beautiful, searchable edition with superb stills. I think you need both.

The digital collections set up by UW Libraries are breathtaking. Check them out here [22].

Some entries on our site intersect with Ben and Lea’s research. See the category Tableau staging [23].

Weisse Rosen (White Roses, 1915). Asta Nielsen.