1914 Kinetoscope Victor Model I Silent Film Projector by the Victor Animatograph Co. From Pinteres [2]t, identified by Robert Van Dusen.

DB here:

The first thing you learn about silent movies is that they weren’t shown silent. The second thing is that they weren’t shown as fast as we often see them. Screened at 24 frames per second (“sound speed”), many films look rushed and silly. Those were shot at slower frame rates, like 16 fps or 18 fps. By the end of the 1920s, though, some were shot faster than sound, up to 30 fps.

Most archives and some cinémathèques and repertory theatres owned adjustable-rate film projectors, so they could provide a smooth flow of motion for most silent films. But what happened when film projectors were junked and replaced by digital projectors? How could the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), that set of files containing the movie and a host of encryption devices, offer the various “silent speeds”?

I wrote a little about this problem in Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies, but afterwards I continued to wonder how archives were coping with the matter once digital conversion was universal. The main problem is that digital projectors don’t currently provide options slower than 24 fps. Both the Hollywood studios that established the digital standard and the manufacturers that implement it simply ignored the history of cinema. Where does that leave archives, which restore, circulate, and show silent films on digital equipment?

So I asked our friend Nicola Mazzanti, Curator of the Cinematek [3] in Brussels, about this problem. Nicola is one of the founders of the Bologna Cinema Ritrovato festival and a major consultant about digital cinema and the preservation of films in the new age. Here’s his typical provocative, pro-active answer.

Why can’t we ever make it simple?

Nicola Mazzanti, Brussels summer 2011. The plaque reads: “Mr. Bill Clinton, President of the United States of America sat at this table on 9 January 1994. He drank coffee and chatted an hour with all present.”

When they try to sell you some new product there is always the sweet thrill that now, finally, all the unpleasantness and the drawbacks, the little things that bothered you in the past, will be gone forever. Then, you realize that the car you bought was a Volkswagen diesel.

With Digital Cinema we were all told that life would be happier once we jumped onto the bandwagon. Distribution of independent films would be easier. All sorts of catalogue titles would flow joyously from the archives to the multiplex. “Alternative content,” including slightly unsharp TV programs and opera with awful close-ups and great sound, would make theatre owners rich.

Many believed the PR. Some of this became true—the usual 10% of it.

Granted, it is easier and cheaper to produce and manage a DCP than a 35mm print. And some classics did find their way to independent or repertoire theatres (the few who survived the digital switch, that is). Several archives, ours included, are enjoying these benefits of the digital switchover. And advertising an 8K or 20K or whatever-K restoration can bring in audiences. But many of us also have tons of perfectly fine 35mm of classics, and they cannot be shown any more. Why not?

*35mm projectors are basically gone.

*Some catalogue owners permit screening only their “restored DCP” (and strictly with English or French subtitles – so much for cultural diversity!).

At the end of the day the number of available classic titles went down, not up.

We could talk about this situation a long time, but let’s home in on one effect of the digital transition. The story I want to tell today is one about those “technical details” that we seem never able to get right. Only the Gods of Cinema know why.

We could talk about screen ratios in this connection, but not today. Today we talk about frame rates.

Toward a standard

Unlike video files but like a strip of film, a DCP consists of a bunch of individual frames that play nicely one after the other. The number of frames that are played back per second is defined by a simple line of code in an XML file. From the point of view of the technology in the server and the DCP format, there is no reason why we cannot play a film at any rate we like, say, 17fps. (Granted, we can’t really run it at 100fps, because of bandwidth, but you see my point.)

This is not the whole story. First of all, there is a need for a highly standardized system, or we would have the problem of a DCP playing well in one theater and at the wrong speed in the next. Then there are other issues, like the frequency of the projector or the link between the server and the projector. I will not bore you with the details. In sum, technical problems make it impossible to build what I had proposed in the first place: a hand-cranked digital projector. (I was serious.)

Yet all these technical problems could be solved, if we took a rather pragmatic approach. (Here, “pragmatic” is the PC term for “compromise.”) That’s what we archivists did, a few years ago.

At the time of publication, the Digital Cinema Initiative specs described something that did not really exist yet. The technology was only almost there. In the hurry to produce a standard that could work, it was perfectly sensible to start with only two frame rates: 24 and 48 (for 3D).

Some time later though, the issue of expanding the frame rates options came back with a vengeance. The strongest push was coming from European broadcasters who wanted to sneak their boring stuff to the cinema screens and thus called loudly for a 25fps frame rate. Then some filmmakers like Peter Jackson and James Cameron fell in love with the idea of higher rates, like 30fps and 60 for 3D (regardless of how this would balloon production budgets).

Soon the issue became geopolitical, with the Europeans pushing hard for 25fps, mostly because they considered it a victory to impose another standard on the Americans—even though they had lost the digital war as a whole. At the end, the Pandora’s box of frame rates had to be reopened, enthusiastically by some, reluctantly by others.

The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE) set up a workgroup where all strong views in favor or against were represented. For the historians among you, it was first called “DC28-10 Ad-hoc Group on Additional Frame Rates” and later “21DC.10 AHG Additional Frame Rates.” We archivists, following our typical model of guerrilla resistance, sneaked onto the panel.

Technically, the archival force was the Technical Commission of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). Actually, it was Torkell Sætervadet and I who were volunteered for this “mission impossible.” Torkell is the world’s greatest expert on projection. He wrote the indispensable handbook for film projection, The Advanced Projection Manual (2006) [6]. His FIAF Digital Projection Guide [7], another must-read, was published in December 2012, the year film projection disappeared.

Torkell and I worked on the frame-rate problem for a couple of years. We mostly revised documents and conducted conference calls late at night (thanks to European time zones). We received some support from the more corporate members of the Workgroup. Many had never heard of lower frame rates, and the concept actually fascinated them. We also benefited from the support of Kommer Kleijn from IMAGO (the European version of the ASC), Paul Collard (then Ascent Media, now Deluxe, a profoundly competent person in the business), and Peter Wilson of High Definition and Digital Cinema Ltd.

The result: We succeeded to a great extent. We convinced the workgroup that silent rates had to be part of digital projection. True, the new standard allows only four other rates: 16, 18, 20, or 22. (To be extra-precise, due to technical issues, 18fps is in fact 18.18181818 and 22 is really 21.8181818.) But four options are quite a lot, and we decided that four were better than none.

So what we called the Archive Frame Rates standard (technically ST 428-21:2011) became part of the SMPTE standards for Digital Cinema. It can be found here [8]. More or less in parallel, other frame rates were allowed: 25, 30, and 60fps. An announcement of this development, with commentary, can be found here [9].

Hurray! But don’t celebrate yet.

The Archival Frame Rates standard is not a mandatory one. The manufacturers of Digital Cinema projectors never implemented this particular standard in their machines. And archives all over the world never requested it before purchasing a projector. That, today, is the roadblock to proper screening of silent films on adjustable digital projection.

Home-made silent speed

Well, what are the alternatives?

One can produce, for example, a normal DCP at 24fps, and then use a simple piece of software (such as EasyDCP) that allows for different speeds if the DCP is played back from a computer. That feeds directly into the projector, bypassing the projector’s server. It works fine, although you have to try out several frame rates until you find the one that does sit well with the refresh rate of your projector. Otherwise, you might have some artifacts onscreen.

Alternatively, if your film’s chosen silent speed is 16fps you can easily triplicate each frame and create a 48fps DCP which would play in most theatres. 20fps would fit into 60fps, when available. For 18 and 22, however, this is no solution; they are tough frame rates anyway.

The problem with these as hoc solutions is that they are not universal. If an archive ships a DCP to another archive, someone acquainted with that file must be in the booth with a computer. Or you can just send the DCP and hope it works. Either of the two digital solutions can be used safely only in your own theatre, basically.

Hence my interest in pushing for a standardized solution. This is, I’m convinced, the best one for bringing silent films to broader public.

So I haven’t given up hope that one of the manufacturers might realize that the Archival Frame Rates standard would be a nice addition to their option package. Particularly if archives and other potential buyers start asking for it.

Does one speed fit all?

The silent frame rates are more complicated than what I’ve just outlined. Let’s go a little deeper, because it’s interesting.

When we refer to frame rates, we tend to use discrete numbers (16, 18…). But like all things analog, frame rates lay along a continuum. That ranged from 16 (sometimes lower) to 24 (sometimes higher). Anybody who worked as a projectionist knows that even with a modern projector equipped with speed variators, the actual speed can change according to the day of the week and the time of the day, depending on fluctuations on the grid.

The same variations occurred, naturally, with hand-cranked projectors and cameras. And early motor-driven machines used in the silent era also suffered unpredictable variations from moment to moment.

As a result, silent films were shot and screened at different speeds. Even the same film would have fluctuations in frame rates from scene to scene or shot to shot.

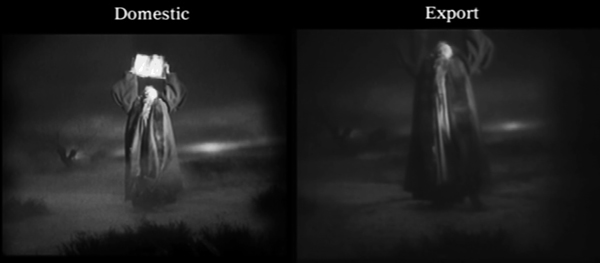

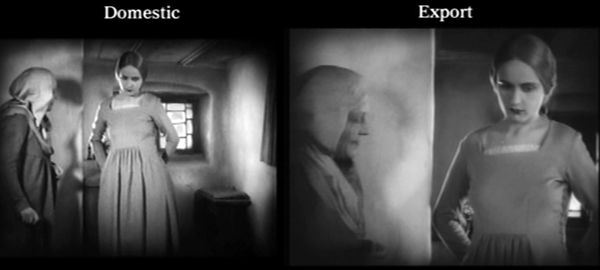

The best example I know personally is Murnau’s Faust (1926). When Luciano Berriatua and I were analyzing the existing negatives of the film, we were puzzled when we compared the two negatives from the original production. Each negative was shot with a different camera. As was common in silent film, the filmmakers provided one negative for domestic circulation and one for international distribution. In production the cameras yielded different angles on the scene–sometimes quite similar, sometimes different.

Nevertheless, the action each one captured was identical. The problem is that the two negatives were different in length!

Why? The cameras were operated by two different cameramen, each hand-cranking at a different speed. The assistant cameraman, undoubtedly younger and more enthusiastic, was cranking faster!

Such a disparity was not uncommon. On the contrary, any archivist confronted with the decision about “suggested frame rate” for a given film is confronted with a choice among many different frame rates. What one writes on the cans is always a speed that fits better on average, not necessarily on each individual shot or scene.

And the reality in archives, cinemathques and everywhere else, is this. Most silent film screenings, if not virtually all, are today executed at one speed throughout the whole picture,

There is strong, albeit anecdotal, evidence that projectionists in the silent era were encouraged to crank different sections of a movie at different speeds. Cues in some musical scores suggest that sequences may have been slowed or speeded up. Projectionists may also have chosen to accelerate chases and battles or slow down love scenes. But there’s no way to know to what extent this manipulation was a common practice.

Personally, I think that we are inevitably looking at a silent film with modern eyes. For one thing, we have a completely different approach to continuity. We ask that a restored silent film be perfectly graded, that its tinting and toning be consistent from shot to shot and scene to scene. But when we examine an original print, particularly from the ‘teens, we realize that our modern concept of pictorial continuity did not apply. It seems to have come into play in the late Twenties or later. Our assumptions about continuity make us consider narrative or visual discontinuity a technical error, or at least a trace of a more cavalier attitude towards continuity. I think that discontinuity of technique was often voluntary and sometimes deliberate.

Fun with frame rates

This point applies to frame rates as well. I am convinced that audiences in the silent era were much more relaxed towards something that we now consider so important. Otherwise, it’s difficult to understand why there so many variations in speed within one picture, and between different versions of the same film.

We should remember as well that we cannot really discuss anything “silent” without taking into consideration that it was a long and complex period of fast evolution and change. A film from the early ‘teens and one made ten years later are two different beasts, and different considerations should apply.

So, to return to our main theme: Are frame rates impossible to vary with a DCP? No—in theory.

If you decide to create your DCP at 24 fps, you can easily slow down each scene at a different rate, if you so choose. Alternatively, if the Archive Frame Rates standard were in use, you could apply your four fixed speeds (16. 18. 20. 22) to different sections of the DCP by simply creating separate “reels” and a correct playlist. This would be a bit like a DCP in which certain parts, such as the restoration credits, are actually a separate file to be played before or after the main body of the film.

Have I tried this? No. Could it work? Yes. Is it worth trying? I am not sure. Again, I am afraid we are looking for a precision that was not really part of a film screening in the silent era.

I remain strongly convinced that “old stuff,” including silent film, has an appeal for the public, and not just for few cinephiles. I also strongly believe that an archive like ours in Brussels should offer a wide range of films on DCP for screenings around the world.

In order to show a silent film in the present environment I have to do some nasty things to the images. I have to slow them down by means of software, even if some solutions work well enough to fool some archivists and historians.

If the alternative is never to show Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910) to anybody, I’d rather use some tricks to make the screening possible in a modern DCP environment. That’s better than making the film invisible. I am also old enough to remember how horrible it was in the 35mm days when there was really no way to show silent films outside a cinematheque. While we wait for archives and manufacturers to implement the fuller range of options, we must keep our films alive.

So when today a nice audience shows up to see Maudite with a pianist in a multiplex in the middle of Flanders (or Ohio or Nebraska), I admit that I’d be unhappy that I had to trick the speed to 18 fps. Yet I still consider it a victory.

For discussion of silent-film frame rates the standard point of departure is Kevin Brownlow’s 1980 article, “Silent Films: What Was the Right Speed?” [12] Brownlow suggests that many American silent films were intended to be screened at a higher rate than the cameraman had used during filming. See also James Card, Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (Knopf, 1994), 52-56, and Jon Marquis, “The Speed of Silence” (2011) [13]. On the revival of interest in high frame rates, see this 2011 article [14] and Pandora’s Digital Box [15].

Nicola has written about other aspects of film preservation in the digital age. See his recent contribution to“The Last Picture Show,” [16] a symposium in Artforum (October 2015), 288-291.Tacita Dean and Amy Taubin contribute to this as well.

The magnificent Masters of Cinema DVD set of Faust [17] includes both the domestic German version and the export version, along with a lengthy comparison of them, from which I’ve drawn my illustrations.

Maudite soit la guerre (Alfred Machin, 1910).