Is Tauriel more powerful than Eowyn? and other questions we shouldn’t have to ask

Sunday | January 19, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

Film franchises now make up a significant portion of Hollywood’s output, and that situation that is likely to linger, at least until we see even more blockbuster flops than in 2013. Prequels are one way of extending a franchise. They’re a risky proposition, though. These days, who ever thinks about Butch and Sundance: The Early Days or Hannibal Rising? How many would defend the idea that the second Star Wars trilogy (now Episodes I, II, and III) are equal to or better than the first (now Episodes IV, V, and VI)?

Quite often the original entry is an adaptation of an existing work, and there is no additional source material for a prequel. The filmmakers have to make up the story, and the risk is that the prequel will end up being an imitation of the original or take the premises of the original too far. This is especially true of literary properties, even if the original author pens the prequel, as Thomas Harris did with Hannibal Rising.

Peter Jackson and company would seem to have been in the ideal situation. They adapted a beloved literary classic, The Lord of the Rings, and it became a popular and critical success. There was already a potential prequel in the form of a second classic by the same author, J. R. R. Tolkien. Of course, The Hobbit was published first, and The Lord of the Rings was a sequel to it. Through sheer chance, however, the fact that the distribution rights for The Hobbit had not been sold along with the other film rights to the two novels, the filmmakers were not able to begin with it. Only after LOTR was out did MGM, owner of those distribution rights, come on board as co-producer, and the film Hobbit became a prequel.

Now Jackson had a book written by the same author and access to considerable material in Tolkien’s appendices. He was working with a team consisting of many of the same writers, designers, and technical experts. They were in a strong position to create a film that had the same look and feel as LOTR. With the added material, the dramatic weight and the length of The Hobbit could balance that of the LOTR trilogy. The two stories could blend seamlessly. Possibly more seamlessly than the original novels, which had some gaps and inconsistencies arising from the fact that The Hobbit was a children’s story published in 1937 and The Lord of the Rings was a longer, more serious novel that came out nearly twenty years later.

Now that The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, the second of three parts of The Hobbit, has been released, perhaps it’s time to check in on how the filmmakers are maintaining it as a lead-in to their LOTR trilogy. Unfortunately, I think some serious problems have arisen that were not present in the The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. Some of these problems arise from departures from the novel that don’t make sense in relation to the original trilogy; some arise from unclear or unmotivated actions invented by the screenwriters; and worst of all, some result from new characters and situations that too closely resemble those in the original trilogy. Whatever is added to the extended version of Desolation and whatever happens in the third part, There and Back Again, the prequel is now flawed.

The Extended Edition of An Unexpected Journey

But first, some unfinished business concerning the first part of the prequel. Almost exactly a year ago, I posted an entry on the theatrical version of Journey. Having already pointed out that there was plenty of material in the Lord of the Rings appendices to extend the two-part Hobbit adaptation to three parts, I defended certain additions to the plot. These were notably the White Council scene at Rivendell and the inclusion of Radagast the Brown, a wizard only referred to in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel (though he does appear briefly in LOTR). After all, the appendices are really for both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, containing additional material for each of the novels.

I was far less keen on the Azog the Defiler plotline, entirely invented by the filmmakers. Yes, there is a scene in the appendices where Azog briefly appears in the battle at Moria, but he dies in that battle. The notion of him chasing down Thorin from motives of revenge is wholly new. I argued that the Azog-related scenes overburdened Journey with extra action that disturbed the balance of the narrative, adding an unnecessary battle at the end that came too soon after what should have been the highlight and climax of the film, the underground escape from the goblins and the Riddles in the Dark scene.

I speculated at the time that some specific scenes eliminated to make room for Azog would be added to the extended edition, perhaps helping to redress the imbalance. Were they, and did they?

The main scenes that I anticipated did get added to the extended-edition DVD/Blu-ray release. I think almost everything added to it is a plus. Most of the new scenes are quiet ones of exposition and characterization rather than frantic action, which the later portions of Journey were sadly lacking. Yet this doesn’t help much to balance the narrative any better, since most of the added bits come in the first half of the film, the half that was already quieter and less jammed with action than the later portions. Still, given how much violent action there is late in the film, any quiet action helps counter it to some degree.

As seemed very likely, early on there is a flashback to Gandalf setting off fireworks at a Hobbit party where he meets young Bilbo for the first time. It’s charming and all too short, zipping by, but at least we see a rambunctious young hobbit very different from the staid, middle-aged Bilbo of Bag End. The contrast helps motivate Gandalf’s disappointment in the adult Bilbo and his remarks about how he has changed. The moment also helps motivate the notion that there is a suppressed Took side to Bilbo’s nature, just waiting to be summoned forth by a pushy wizard.

Another extra early scene shows Bilbo, nervous after the visit from Gandalf, shopping for the ingredients for his supper (including the fish later consumed so thoroughly by Dwalin). The brief scene doesn’t add much to the plot, but it serves to introduce the Shire and Hobbiton to those who may not have seen LOTR, and it provides some humor after the tense ending to the initial conversation with Gandalf.

As I anticipated, the Rivendell interlude is expanded. In fact, the bulk of the new and extended scenes occur here. Bilbo wanders around Rivendell, clearly overwhelmed by its beauty. He not only sees the shards of Narsil but stares at the nearby mural of Isildur cutting the Ring from Sauron’s hand. Thus Bilbo sees the Ring shortly before he finds it himself, though there is no one present to tell him what he’s looking at. He also chats with Elrond, who says he is welcome to stay in Rivendell. He presumably means that Bilbo need not accompany the Dwarves when they continue on their journey, but a bit over sixty years later Bilbo will end up living there.

The extra comic bits with the Dwarves, including Bofur’s song, are perhaps entertaining enough, though they continue to film’s general tendency to make them overly boorish.

The White Council scene is extended mainly by Gandalf’s exposition about the Seven Rings of the Dwarves, which Saruman dismisses as irrelevant. The Seven Rings are not referred to in the theatrical version of The Desolation of Smaug, though presumably they were put into Journey for a reason and will return at some point, if only in future extended versions.

The scene with the Great Goblin is stretched out, as he is allowed to sing the Goblintown song from the original book. I think Barry Humphries was an inspired choice to provide the Great Goblin’s voice, so having a little more of him is welcome.

Luckily, there are no extra scenes involving the Azog plotline.

Caution: From here on there are major SPOILERS for the concluding part, The Hobbit: There and Back Again as well as for Desolation.

A better film–if you don’t think too much about it

The reaction to Desolation has been strangely split. On the whole, the critical establishment has heralded it as an improvement on Journey. No long setup of thirteen Dwarves and their quest–just a long series of exciting action scenes culminating in an extraordinary special-effects achievement with the dragon Smaug. The Dwarves’ escape from Thranduil’s realm in barrels rushing down a river with a running battle involving Orcs and Elves has been compared, in the usual reviewers’ cliché, to a thrilling theme-park ride. The battle with the large spiders has also been lauded.

Many fans of Peter Jackson’s other films in the series love Desolation as well and have been going to see it multiple times. Yet fans who know Tolkien’s books really well, while often enjoying the film, have been far more grudging and selective in their praise.

This is largely because Desolation departs far more radically from the novel than any of the previous four films have. New characters have been invented, most notably the female Elf Tauriel, and new scenes fabricated, as with Gandalf’s disastrous solo visit to Dol Guldur, where he ends up imprisoned, or the hectic string of suspense and action scenes at Lake-town. Thranduil briefly appears in the book, but his role as an enemy to the Dwarves has been expanded. The scene of the Dwarves entering Erebor and trying to kill Smaug with molten gold has no parallel in the book.

Inventing scenes needn’t be a problem. Many have complained about the made-up warg attack that ends in Aragorn’s apparent death in The Two Towers, but it is integrated fairly well into the plot. Departures from the original Hobbit novel may be annoying to some, but one should ask how well they fit into the cause-and-effect flow of the plot and into the film as a whole. More specifically, the filmmakers were trying to make The Hobbit into a more substantial film than simply following the book would have allowed. They had to do so in order to blend smoothly into the same world as the LOTR film. The question, then, is really whether the changes 1) are logical in themselves and in relation to the other trilogy, and 2) are an improvement on what the filmmakers could have accomplished had they stuck closer to the story.

Unfortunately, I think that in many cases the new and extended characters and scenes are not as strong as they could have been. More problematically, certain choices steal inspiration from the LOTR film trilogy and in the process undermine the dramatic impact of some of its scenes. This would seem to be something to avoid at all costs in creating a prequel: making the original seem less fresh and dramatic.

Back when I wrote about the decision to split The Hobbit into three parts, I defended Jackson from the accusation that he was clinging to this franchise because he had lost some of his inspiration and didn’t know where to go once the Tolkien adaptations were finished. I don’t know whether it’s true that such a lack of inspiration led to Jackson’s choice to direct the film that he originally wanted to assign to someone else. My point was simply that there was enough material in the novel and in the appendices to expand the film to three parts, if the screenwriters took advantage of that material and fitted it into the plot skillfully. The addition of the White Council/Dol Guldur plot line, largely based on brief statements in the appendices, suggested that Journey was following that path. I don’t think Desolation continues that pattern of relying on snippets from the original books–and there are some that go unused–to flesh out into new story material. This change is to its detriment.

There have been some thoughtful essays suggesting that the film falls down in its invented portions. Timothy R. Furnish, a long-time columnist for TheOneRing.net, has contributed an essay criticizing the main changes from the book. Furnish admits to being a purist, but his claims about the changes suggest that they do not benefit the film. For example, he points out that the plot line involving Gandalf’s and Radagast’s visit to investigate the tombs of the Nazgûl is “rather confusing” and “seems forced and, frankly, unnecessary.” I don’t completely understand that plot line myself, given that it’s not in Tolkien and not explained very well in the film. Elrond said at the White Council meeting that the spells holding the Nazgûl in their tombs were unbreakable. So far there’s no explanation as to how they escaped. Are most viewers able to connect those empty tombs to the Black Riders we had first met early in Fellowship? I doubt it.

The inclusion of this tangential plot line also means that Gandalf is lured away from his commitment to the Dwarves’ quest not once, but twice, which isn’t very effective dramatically. Galadriel goads Gandalf into investigating the tombs, and Radagast persuades him to explore Dol Guldur. Thus the two of them end up being responsible for his defeat by Sauron while themselves not offering much help. Gandalf also looks weak and indecisive, capable of being talked into an unwise course of action.

How could this have been handled better? Stick to the book. Tolkien never tells us what happened to the Nazgûl in the centuries immediately following Sauron’s defeat and Isildur’s taking of the Ring. It just doesn’t matter. Why drag it into the film? (Possibly extra material in the extended version will better explain this minor plot line, but I doubt there will be anything new relating to it.)

Furnish points out something that has been universally criticized among fans of the books. The episode at the home of Beorn, the large man who can change into a bear, has been so truncated as to be rendered almost pointless. Sure, the design of his house is nice, but why bother? Yes, it offers a brief refuge from the pursuit by Azog’s band–but that just raises the unanswered question as to how Azog found them again after they had been carried so very far by the eagles. The filmmakers needed to include Beorn, since he should return to play a major role in the third part. At least his presence strongly hints that they haven’t eliminated him from that major role. Jackson has assured fans that there will be “a couple more scenes in the extended cut of this film, and some more of him, which I won’t be describing, in the third movie!”

A better approach? In the book, the company have lost all their ponies and supplies in the goblin-caves adventure and are in need of rest and assistance, not rescuing from Orcs. They stay with Beorn for a few days. He’s a fascinating figure in the book, with his giant bees and animal servants. He’s also not the defeatist, lonely figure of the film but a pugnacious guardian who keeps a small region east of the Anduin River free of goblins and wargs. Presumably the extended edition will at least give him a little more screen time. This could have been a chance to add some of the charm and humor of the book to a film that sorely lacks them, in its second installment at least.

As Furnish writes, Bard is a “grim-voiced and grim-faced” leaders of Lake-town’s archers in the book, not a ferryman and smuggler with children to feed. Yet, as Furnish says, “making Bard less of a recalcitrant loner is defensible.” I’d say more than defensible. It may be the only major change that improves on Tolkien, at least in one way. Tolkien’s decision to have Smaug killed by a very minor character was probably a mistake, and fleshing Bard out into a significant figure works reasonably well–though it also is encumbered by the whole conceit that the Dwarves and Bilbo have to be smuggled into Lake-town and that Bard is at odds with the Master of Lake-town and his assistant Alfrid (the latter an invention of the filmmakers). In the book, the Dwarves are welcomed to the town from the start, as potential slayers of the dragon and sources of future prosperity. The chapter about Lake-town is titled “A Warm Welcome.”

Furnish also makes a more general point: that both parts of The Hobbit far are short on sympathetic characters. LOTR is full of heroes–and even Boromir, after trying to take the Ring from Frodo late in Fellowship, redeems himself by trying to save Merry and Pippin. But in Jackson’s Hobbit, few of the characters beyond Gandalf, Bilbo, a few of the Dwarves, and Tauriel are particularly admirable. Dwalin, ever suspicious, even suggests killing Bard and taking his boat. Not nice.

Whether or not audiences perceive the characters as Furnish suggests, there is no doubt that LOTR involves characters fighting for the common good and making considerable sacrifices to do so, while most of The Hobbit‘s characters are in contention over the wealth they would gain if Smaug can be killed. There’s also a prominent revenge motif. (Again, Gandalf, Bilbo, Galadriel, and Elrond excepted, and the latter two essentially don’t appear in Desolation.) The Dwarves are a greedy bunch in Tolkien’s novel as well, but The Hobbit is a more comic, more conventional fairy tale than is LOTR, and besides, none of his Dwarves ever behave as callously or as crudely as the film versions do.

This problem of unpleasant characters is particularly noticeable with Legolas. He has been made so intolerant, so offensive, and so callous that many fans would rather he had been left out altogether. Certainly the Tauriel-Kili romance could have worked without him. Perhaps he will improve a bit by the end of the third part, but he is far from the sympathetic Elf that became the idol of fangirls in LOTR. He even looks different, as if Orlando Bloom’s entire face has been Botoxed and too light a shade of blue has been used for his contacts. Here’s a case where purely financial considerations may have played a prominent role in the decision to insert him into The Hobbit.

How could all this have been avoided? In part by trying to achieve something of the sense of fellowship that made LOTR so appealing. Avoid overloading the film with characters who act through motives of revenge and distrust. The invention of the Orc-pursuit subplot is largely to blame for this, as is the caricatured depiction of the Master of Lake-town. The focus should really be on Thorin’s growing obsession with the Dwarves’ lost treasure, which eventually will lead to his break with Bilbo, despite all the latter’s heroic rescues. That obsession is brought up a few times, but it’s obscured by the general emphasis on revenge and greed.

Once more on the issue of padding

Another insightful piece, written by Michael Martinez, takes on the question as to whether Desolation‘s story has been padded out. He points out that in fact a great deal has been cut out of the book, trimming what was already supposedly too short to form the basis for two or three lengthy films. As Martinez writes, the crossing of Mirkwood has been compressed from weeks into what apparently are two or three days. The passage where they wander, dazed, in the woods is the only point at which much time can have passed, and we’re given no sense of how long they are lost before Bilbo climbs the tree–a moment that at least keeps the book’s scene of him delighting at the butterflies he encounters. In the novel, there are other adventures in the woods, and the Dwarves apparently spend about two weeks locked in their cells in Thranduil’s realm, during which time Bilbo, wearing the Ring explores the caverns and finally figures out a way to free them.

The filmmakers then add all sort of things that are not in the book. Is this new material, Martinez asks, padding? He seems not to think so, but I’m not so sure. If the new material is, like the whole Azog subplot, unnecessary and even detrimental to the balance of the narrative, doesn’t it count as padding–especially since it crowds out such things as a more satisfying episode involving Beorn?

Take whole running battle as the Orcs chase the fleeing Dwarves in their barrels down the river and the Elves chase the Orcs. (In the book, the barrels are sent down the chute into the river and simply drift downstream until some Elves steer them along to Lake-town, which is on the near side of the lake.) Yes, the river escape and battle are exciting and fun to watch, if overlong, but they point up yet another problem of balance in this and other action scenes. The barrels chase make the Orcs look remarkably ineffectual. Tauriel and Legolas pick them off at a great rate, both in this scene and in the Lake-town skirmishes. In the river scene, the Orcs do manage to kill some anonymous Elven guards at the sluice gate, and they wound Kili, but they ultimately create more delays than damage and eventually lose their quarry. Such efficient killing of Orcs happens to some extent in Journey as well, but as the Dwarves’ bowman Kili does not have the athletic virtuosity of Legolas and Tauriel, the cannon-fodder nature of the Orcs is less obvious. By the end of Desolation, though, can we really take them that seriously?

The messiness of the Azog/Bolg revenge plot line culminates (at least for now) in the Lake-town scenes, with sinister forces multiplying to a confusing extent. As Martinez puts it, “But with Orcs, elves, dwarves, and the Master’s spies all sneaking around Lake-town I really felt like we had left The Hobbit behind and entered the world of ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ or something.” New or not, I would say that such antics constitute padding, in this case via Jackson’s penchant for extending and multiplying dangers and fights.

Certainly all these invented characters and scenes aren’t necessary because there really turns out not to be enough material in The Hobbit and the LOTR appendices to make up three parts. One puzzling aspect of Desolation is that it fails to pick up plot lines the filmmakers themselves had set up in Journey. The latter, despite its awkward concentration of slower sequences early on and rampant, almost continuous fighting in the second half, had established a pretty good set of plot lines (excepting the superfluous Azog one). They’ve all but disappeared.

I speculated in my entry on Journey that we might discover in part 2 that Saruman was already corrupted by desire for the Ring and wants to prevent an attack on Dol Guldur because he’s already looking for the lost Ring himself. That would have been interesting and true to the information in the appendices. Instead, Saruman doesn’t appear in Desolation. Was bringing Saruman into The Hobbit (where he doesn’t appear, given that Tolkien didn’t invent him until well into the drafting of LOTR) just a little salute to a popular actor? Or will he return in the third part to take part in the attack on Dol Guldur? In which case, will he actually be helping the other White Council members, or doing something devious? (In the appendices, we learn that he did help, mainly to get Sauron away from the area near Dol Guldur where the Ring slipped off Isildur’s finger and sank to the bottom of the Anduin; Saruman himself has been searching the river.) The filmmakers created Saruman’s scenes in The Two Towers so skillfully that his absence here is disappointing. If he is going to reappear in the concluding part, it would seem a good idea to at least mention him. If he isn’t, some way of motivating his absence would have been helpful.

Similarly Radagast, whose insertion into the first film I defended, is barely in this one. He doesn’t do much when he is present, either, mainly pressing Gandalf to investigate Dol Guldur and then, once they reach it, going off to take a message from Gandalf to Galadriel. Will Radagast play a significant role in the final part? One would think so, but at this point I’m not betting on it.

That reminds me

Most crucially, I think, instead of using these already established characters in Desolation or just sticking more closely to the book, the filmmakers have introduced many new elements that are essentially diminished versions of characters and events in LOTR. That strikes me as a bad idea and perhaps really does betray a lack of inspiration. Already fans of the LOTR films have complained that so many echoes of LOTR appear in Desolation. Worse is to come, though. When people view LOTR as part of a series of six parts beginning with The Hobbit, they will end up seeing things in LOTR as echoes of Desolation. The result will be to rob LOTR of some of its originality and effectiveness.

Take Tauriel. She’s a pleasant, admirable character, with a stubborn, headstrong streak that keeps her from being bland. Evangeline Lilly’s performance strikes me as excellent. A lot of fans worried about her inclusion in the film but came to like her. They seem to see her as blending well into the world of the film. But there’s a reason for that. She does come from the world of LOTR.

Was it really a good idea to add a major character who’s basically a blend of Arwen and Eowyn? Doesn’t she make both of those characters less distinctive?

If a lowly Sylvan Elf like Tauriel can rescue Kili from a giant spider and later use the herb athelas (“Kingsfoil”) to heal his wound, are LOTR’s similar rescues of Frodo by Aragorn, Arwen, and even Sam not rendered a bit less impressive? (In the book, Bilbo does all the saving of the Dwarves from the spiders; no Elves appear.) Later, the arrow that strikes Kili is referred to as a “Morgul” weapon that will kill him. Thus it resemble Frodo’s wounding by a Morgul blade by the Witch King at Weathertop in Fellowship. Again, Frodo’s wounding, which seems unique and bound up with the Ring’s evil influence, is cheapened. How can just any random Orc be carrying a weapon with a Morgul spell on it, something we were led to think is unique to the Nazgûl (and in the book, such weapons are). In Bard’s house, Kili’s vision of Tauriel surrounded by glowing light recalls Frodo’s vision of Arwen when she approaches him in Fellowship. Arwen’s stature is lessened by the suggestion that all Elven women can appear this way to mortals. (There’s a reason why Thrandruil doesn’t want his son to fall for Tauriel, though I’m sure he would be thrilled were Arwen to agree to marry Legolas.)

With Tauriel’s limitless athleticism and fighting capabilities, won’t she steal some of the thunder from one of the LOTR film’s most beloved characters, Eowyn? Across Tolkien’s two novels, Eowyn as a female warrior of Rohan was unique. She was unique in the films, too, until now, when Tauriel popped up to dispatch dozens of Orcs with the same aplomb that Legolas does. Did the writers never consider this problem? Was there no other way of creating a “strong” female character besides making her a fighter?

For that matter, why not do something more with the strong female character they already have, Galadriel? Why does she send Gandalf off alone to do the dirty work of investigating the tombs and Dol Guldur? After the White Council scene Galadriel assures Gandalf that she’ll come and help him if need be. Why not just give him a hand to begin with and not wait until Gandalf nearly gets himself killed. In the book Galadriel is ultimately the one who destroys Dol Guldur at the same time the Fellowship and other characters are down south attacking the Black Gate and destroying the Ring. It’s not as though she’s a shrinking violet.

Beyond being the strong female, Tauriel is also there partly to create the love triangle between her, Legolas, and Kili. That romance, though, is sketched out in terribly conventional terms. Tauriel’s interest in Kili is expressed through her remark that he’s tall for a Dwarf, and the final moments between them after she has healed his wound turn distinctly maudlin, with him failing to recognize her and asking weakly if she thinks Tauriel could have loved him.

One of the fans on the TORn Message Boards, ec1988, has started a thread called “The inclusion of Tauriel diminished Legolas.” There simplyaven argues that the Tauriel-Kili romance to some extent presages Legolas’ friendship with Gimli and undercuts its presentation in LOTR as an unusual, even unique overcoming of racial hatreds. That seems right. Her “Aren’t we part of this world?” also echoes Merry’s question to Treebeard when the Ents resist the idea of attacking Saruman. (This isn’t the only line repeated almost verbatim from LOTR.)

Another distinct echo of LOTR results from Gandalf’s fight with Sauron in Dol Guldur. It looks remarkably like his duel with Saruman in another tower, Orthanc, in Fellowship. Saruman takes Gandalf’s staff during that one, while Sauron seemingly dissolves Gandalf’s staff into dust:

This moment also echoes the scene in Return of the King where the Witch King knocks Gandalf the White off Shadowfax and dissolves his staff (in the extended edition only).

By now Gandalf has lost a number of staves across the five parts of the epic tale. It has become a sort of unintentional running joke on discussion sites as fans tot up how many staves Gandalf has lost and where he might be getting the replacements. Posts include photos to demonstrate the slight differences among them. One relatively brief example from the Message Boards on TORn comes from 2008–years before The Hobbit included at least one more destroyed staff. As moderator Ataahua remarked, “Back in the day, someone on TORN wondered if Gandalf had a locker of spare robes and staffs at Rivendell, as if it were a handy bus station. :)” Whether Radagast will give Gandalf his to replace the one destroyed by Sauron is a current topic of discussion.

But getting back to the Dol Guldur battle. Sauron slams Gandalf to the ground, then tosses him up so that he’s “velcroed” to the wall–pretty much as Saruman had done:

In Fellowship, Saruman imprisoned Gandalf on a tiny space at the top of Orthanc. Sauron suspends him in a small cage. I wonder if someone watching all six parts straight through might not find the Saruman-Gandalf battle a bit ludicrous because it is so similar to the “earlier” one. (To me, the wizard-duel was already somewhat ludicrous–and of course, it didn’t happen in the book.)

There are other signs of Desolation cannibalizing ideas from LOTR. The invented character of Alfrid, assistant to the Master of Lake-town, is a lot like Theoden’s slimy, treacherous adviser Grima. Thranduil is like Denethor in his refusal to consider the welfare of anyone beyond the boundaries of his own realm. Furnish calls the Master of Lake-town “the Goblin-King with a comb-over and more clothes,” suggesting a cannibalization from within The Hobbit as well.

Gandalf the Wimp

In this film, the writers don’t seem to know what to do with Gandalf. Midway through the book, he simply leaves the Dwarves and Bilbo at the edge of Mirkwood to take care of “some pressing business away south”–as he had planned from the start to do, so there he isn’t suddenly abandoning them. He returns in time to participate in the Battle of Five Armies, near the end of the novel.

Tolkien was smart enough to know that Gandalf was simply too powerful to keep around all the time. Where’s the suspense if you’ve got a wizard along to solve problems like capture by trolls or goblins? So he invented various devices to take him away from the action for stretches of time. (These became more complicated in LOTR; I devote part of a chapter of my book-in-progress to these tactics.) Only near the end of The Hobbit novel do we learn that Gandalf and the White Council have driven the Necromancer out of Dol Guldur. Indeed, Tolkien invented the “Necromancer” simply as an excuse to leave Bilbo and the Dwarves alone, forced to defend themselves. It was only by happy accident that this sinister figure, barely mentioned in the novel, was available to become the source of LOTR’s supreme villain.

So why doesn’t Desolation have Gandalf go off to do his “pressing business” and then concentrate instead on Mirkwood, Thranduil’s imprisonment of the Dwarves, the trip by barrel to Lake-town, and above all on Bilbo’s maturation? I have to believe it’s because Ian McKellen is arguably the biggest star involved in these films. True, others have also become famous as a result of appearing in The Hobbit, but back when the film was being written and shot, Ian was central. In the credits his name appears before that of Martin Freeman.

The problem confronting the filmmakers was that Gandalf is a supporting character in The Hobbit, albeit a major one. (I would argue that he and Frodo are the two protagonists of LOTR, the novel.) It would be appropriate for him to be absent for most of the second half of Desolation, but clearly the filmmakers felt they couldn’t afford to give up their top star for so long. Hence they invented scenes to give him something to do. The obscure mission to the tombs in the High Fells is one such scene. In terms of the plot as a whole, however, it could easily be done without.

More crucial, though, is Gandalf’s invasion of Dol Guldur, his challenge to the hidden forces there, and his losing battle with the Necromancer, now revealed as Sauron. The fact that he ends up helpless and in need of rescue raises yet another question: Why does he do such an idiotic thing? No reason is provided. He is certain that he’s going into a trap, and he has no idea what’s waiting inside for him. What could he possibly hope to accomplish? (If he were going in to try and rescue someone held prisoner inside, that would be another matter.) I think we’re to take it as a brave move on his part, and he does manage to hold his own against Sauron for a short time. But basically it’s a huge mistake on the part of a wizard we’re supposed to consider wise.

The sensible thing for Gandalf to do would be to go and alert Galadriel, who presumably has returned to her home in Lothlorien. That realm is situated relatively close to Dol Guldur, almost directly across the Anduin. Gandalf and Galadriel could summon the White Council and gather Elvish troops to lead an attack on the tower. In the book, that’s what Gandalf’s “pressing business to the south” is.

In general the Gandalf of the films is a far weaker, more vulnerable figure than the one in the books. I cannot imagine the Gandalf of the books would say that he’s afraid and that having Bilbo along on the quest gives him courage, or that he would need such reassurance and guidance from Galadriel. The Witch King could hardly knock him off his horse. In Fellowship (the book) Gandalf manages to hold off the nine Black Riders all night when they attack him on Weathertop. He doesn’t kill any of them, but he manages to escape unscathed.

Moreover, in the book Gandalf has been to Dol Guldur twice before, long before the action of The Hobbit. The first time, nearly 900 years earlier, Sauron is hiding there, slowly regaining physical form. Tolkien’s summary of the event in Appendix B is terse: “Gandalf goes to Dol Guldur. Sauron retreats and hides in the East. The Watchful Peace begins. The Nazgûl remain quiet in Minas Morgul.” Later Gandalf sneaks into Dol Guldur to as a spy and discovers that Sauron has returned. He also finds Thrain, Thorin’s father, dying, and receives from him the key and map that he later gives to Thorin in Bag End. (One would think that a flashback to that scene would have been dramatic and suspenseful.)

Tolkien never tells us what Gandalf did to make Sauron retreat. Maybe just the wizard’s presence frightened him away. Similarly, how he managed to spy inside Dol Guldur remains unexplained. The point, though, is that the filmmakers have made Gandalf weaker primarily to generate even more suspense and violent action and to set up a rescue of the hapless wizard that will surely involve an attack on Dol Guldur in the final part. Never mind that Gandalf’s invasion of Sauron’s stronghold in Desolation makes no sense.

Gandalf isn’t the only one who is made less powerful and dangerous in order to generate a grand action set-piece. Even the villain of the title is made to look rather foolish.

Smaug the Clueless

There is no question that Smaug as a CGI creation is a marvel, and Benedict Cumberbatch provides his voice, as manipulated by the sound crew, very effectively. Throughout his initial scene with Bilbo, which sticks pretty closely to the book, he seems appropriately menacing, sly, and playful in the manner of a cat toying with its prey.

As soon as the Dwarves join Bilbo inside Erebor, however, Smaug is revealed to be strangely ineffectual.

Once the Dwarves decide on their strategy of flooding Samug with molten gold, they split up to take separate routes to the forges. Time and again they manage to elude the beast as he searches for them. At once point he passes right above Thorin’s group and fails to notice them. Wouldn’t Smaug be glancing in all directions as he moved? And so much for his vaunted sense of smell. At one point Thorin leaps into space to avoid a blast of fire (below) and manages to catch hold of a chain hanging conveniently in his trajectory. Smaug follows him, curling around the dangling Dwarf but makes no real attempt to kill him. At one point, Thorin even ends up standing astride the creature’s mouth for a few moments. Now that he has found Thorin, Smaug doesn’t do the obvious–open his mouth and take a bite of him. Later, when Thorin stands exposed on the giant mold full of molten gold, he and Smaug are face to face. The dragon, instead of incinerating him, trades insults. (Of course, movie villains often miss their chance to vanquish their foes, in a convention termed by Roger Ebert “The Fallacy of the Talking Killer.”)

There is so much in the sequence of the Dwarves’ attempt to kill Smaug that is distractingly implausible. Just as the lengthy falls in the Goblintown scene of Journey never seemed to cause so much as a broken bone, in Smaug’s domain the dragon breathes great sheets of fire repeatedly and never seems to singe the Dwarves. When Thorin’s jacket is set afire, he simply takes it off and keeps running.

How could this vast quantity of gold be melted so quickly? How could Thorin ride a river of molten gold in a metal wheelbarrow and survive? Why does the giant Dwarf king’s statue, when the mold is pulled away, stand for several seconds as Smaug admires it before suddenly gushing into a golden lake that momentarily overwhelms the dragon? And why, if Dwarves know so much about dragons, does it not occur to them that a creature full of fire couldn’t be killed in this fashion? Why would Smaug keep bashing down columns and other parts of the “building” which he considers his and where he plays to spend the rest of his life?

As with Gandalf, the filmmakers have robbed Smaug of much of his power in order to concoct a big action scene as a climactic lead-in to the cliffhanger. Admittedly, the shot of Smaug shaking off the coating of gold into tiny fragments is spectacular, and with that he regains something of his original menace. Yet the cliffhanger works mainly because we assume that the men, women, and children of Laketown, in their wooden houses, will be easier for the dragon to kill.

Mistakes, confusion, and omissions

There are a lot of unexplained, unmotivated things about Desolation. Some are relatively minor, such as how Smaug, who has been alone with his treasure ever since attacking Erebor, could know that Thorin had in the interval before returning gained the sobriquet “Oakenshield”? Or why does Lake-town, which seems to station guards and customs official at every possible entry into the city and spies everywhere, not keep a single guard on the broad, long bridge that links it to the shore?

As in parts of LOTR, there is some jiggery-pokery with time and space. Azog is summoned from a forest near Beorn’s house back to Dol Guldur, which he reaches during the same single night that the Thorin and company spend in the house. Gandalf remarks later that to go around Mirkwood would involve hiking 200 miles north and twice as far south (one fact that does come from the book). Dol Guldur is near the southern end of Mirkwood, so we are to believe that Azog’s warg is speedy enough to cover perhaps 350 miles in several hours. Of course, films play with compression of time quite frequently, but this case is very obvious, since there is an immediate return to the Dwarves’ group still at Beorn’s house.

There are other noticeable causal inconsistencies that make a greater difference in the plot. It was set up in The Two Towers that Galadriel and Elrond could communicate telepathically from a considerable distance. Galadriel and Gandalf speak mentally to each other in the White Council scene. Galadriel seemingly disappears instantly at the end of her talk with Gandalf after the White Council.

Now it turns out that Gandalf apparently can disappear, as he does during his battle with Azog, just before he meets Sauron. Why doesn’t he just stay invisible until he has escaped? Moreover, Galadriel speaks mentally to Gandalf from somewhere, presumably fairly far away. Yet he can’t speak to her that way and must send Radagast with a message to her.

What are the rules here? Why does Galadriel seem more powerful than Gandalf? Who are the wizards and how do they as a group relate to the Elves? The filmmakers could have dramatized a major passage in the appendices that explains who the wizards are, messengers sent by the “gods” of Arda to aid and advise the peoples of Middle-earth in their struggle against Sauron. Then we might be left with fewer crucial questions about these powerful figures, and some reliable premises could be established. LOTR does end with the subtle revelation that Gandalf, Galadriel, and Elrond have the Three Rings of the Elves. (Look quick or you’ll miss them.) The fact that Gandalf has one of the Three comes from that passage on the wizards that I just mentioned. Why ignore that passage, one of the precious few that do relate directly to the action of the White Council plot line?

Again, I think this happens partly because the filmmakers have adopted a tactic of weakening powerful figures like Gandalf and Smaug in order to generate more suspense and big action scenes.

There’s another decision that I think creates confusion. Yes, Azog, the character I dislike both in himself and for his revenge plot line’s unbalancing the film’s scenes, continues to intrude at intervals. As I had speculated, he turns out to be a minion of Sauron. There is still no explanation as to how Sauron could know that Thorin and company have set out from Hobbiton to Erebor and thus direct Azog as to where to hunt for him. For some reason, Bolg, another uber-Orc (above), shows up and summons Azog to Dol Guldur to consult with Sauron–presumably to help prepare his army for a big attack on … something. Then Azog sends Bolg off to take his place and continue the hunt for Thorin. Given that the two seem interchangeable, this whole replacement of Azog by Bolg makes little sense, except presumably to try and inject a little variety into the repetitious revenge plot. Little is the operative word.

One final point. In my previous entry, I mentioned that in Journey the filmmakers did a good job of planting links to LOTR: Saruman’s obstructionism, Galadriel as a powerful figure, Bilbo’s immediate love for Rivendell, the stone trolls seen in Fellowship, the frame story involving birthday-party preparations, and Bilbo’s wealth from the trolls’ hoard. Desolation has far less of this. There’s the picture of young Gimli that Legolas sneers at. There’s also Bilbo’s reaction to the corrupting power of his newly acquired Ring. I think his reaction is overdone. Only a short time after finding it, he seems at least as obsessed with it as we see him sixty years later, at the beginning of Fellowship. Good thing it’s a giant spider that he thinks is trying to take it from him, not one of the Dwarves. Shades of Smeagol! Apart from those added elements, there is little attempt to stitch Desolation a little closer together with LOTR.

Despite everything I’ve laid out here, I enjoy much of Desolation, and it has many good things in it. As usual, the sets, costumes, makeup, and all technical elements have been achieved with the utmost care and imagination. Quite apart from the complex movements of Smaug, with his long body and tail looping through the enclosed spaces of Erebor, there is much to admire. The big action sequences are quite fun. The acting continues to be excellent in most cases, particularly Martin Freeman as Bilbo. Although the hobbit no longer seems the center of his own story, Freeman manages to make every scene he is in a delight and to capture something of the feeling of the book.

Taken as an autonomous film, and despite its lapses in motivation and logic, it offers considerable entertainment and enjoyment. But as the second part of a series, it has gone off the rails, much as the Dwarves lose the Elvish path in Mirkwood. I suspect it will turn out to be the weakest of the six parts. At this point there is little if anything to be done to remedy this. (I cannot imagine that the extended version of Desolation will ameliorate the problems much, though I hope it will do so a little.) We are stuck with Tauriel, Bolg, and a weakened Gandalf for the third film. Still, I hope that There and Back Again will steer more directly toward links to LOTR. We shall see the Battle of Five Armies, and Jackson is nothing if not adept at big battle scenes.

What we can take away about prequels here is simply that filmmakers must not only make an original film in itself but must take utmost care to make it serve the franchise as a whole. Through the insistence that there must be a strong female character no matter what or Jackson’s frequently expressed justification that he added something simply because it would be fun, The Hobbit no longer fits well with The Lord of the Rings. That’s a pity, because up to now the filmmakers had been doing so well.

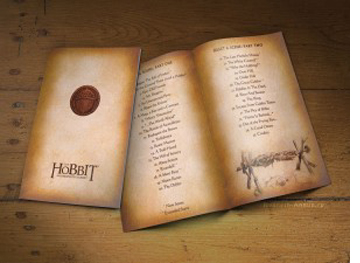

Purchasers of the extended version of AUJ will note that the packaging is not quite as impressive as that for the LOTR EEs. There is no booklet with John Howe and Alan Lee illustrations, nor one of the very helpful indices indicating which chapters are new or expanded and offering a map through the supplements. Fortunately a dedicated Russian fan, TheHutt (editor of the website Henneth Annun), has created one (left), with a remarkably accurate simulation of the design and contents of the LOTR booklets. The pages can be downloaded here. (Scroll down for the English-language version.) Kudos to him!

Purchasers of the extended version of AUJ will note that the packaging is not quite as impressive as that for the LOTR EEs. There is no booklet with John Howe and Alan Lee illustrations, nor one of the very helpful indices indicating which chapters are new or expanded and offering a map through the supplements. Fortunately a dedicated Russian fan, TheHutt (editor of the website Henneth Annun), has created one (left), with a remarkably accurate simulation of the design and contents of the LOTR booklets. The pages can be downloaded here. (Scroll down for the English-language version.) Kudos to him!

For those interested in the saga of Gandalf’s loss of staves. The Dol Guldur duel is chronologically the first time Gandalf loses a staff. Saruman takes the next one in Fellowship. The replacement is lost when Gandalf strikes the Bridge of Khazad-dûm with it, and bridge and staff both shatter. In his new incarnation revealed in Towers, Gandalf gets a white staff, which is destroyed by the Witch King in Return (extended edition). He has a duplicate of it in the Grey Havens scene at the end. Five staves–four of them destroyed–and counting. In the book the only loss of a staff comes at the breaking of the Bridge.