Our Sunhi (Hong Sangsoo, 2013).

DB here:

I’ve complained here [2] and there [3] about the rudimentary staging of scenes in mainstream American movies. (Short version of common practice: Cut a lot and move the camera instead of moving the actors.) But just as rare as complex staging, in the age of intensified continuity cutting [4], is the sustained and stable two-shot.

Two actors exchanging lines in a continuous, unmoving take was one building block of mature sound cinema. Today’s directors almost never resort to it. Their face-offs are “given energy” by a drifting or arcing camera, or lots of cuts, or, if they feel like moving the actors around, the Steadicam walk-and-talk [5].

But the prolonged, balanced two-shot can yield remarkable results. A medium-shot or medium-long-shot framing can work to a human dimension, giving prominence to the actors’ bodies. It doesn’t let their surroundings swamp them, and it doesn’t reduce them merely to faces. It lets the actors act with not just facial expression but with their posture and their upper bodies. And it nicely balances dialogue with the flow of pictorial information. We can watch both actors, with one reacting to the other, as in The Marrying Kind (1951).

Sometimes the two-shot is played with the faces in profile, as in early sound pictures like The Criminal Code (1931).

But directors quickly understood that if you prefer, you can angle the actors so that we get a 3/4 view of one or both. The tactic sacrifices realism (who stands in such ways in real life?) but it’s a piece of artifice we gladly accept. It’s visible in my Marrying Kind example, as well as here in Two Weeks Notice (2002).

Of course two-shots are still with us, but they usually serve to set up passages of shot/ reverse-shot cutting. The sustained two-shot carrying long stretches of dialogue is increasingly rare in Hollywood cinema. It surfaces more often, I think, in indie works (Jarmusch, Linklater, and Hartley, for instance), European films (Garrel, for instance), and perhaps most notably some Asian films.

For reasons not yet well understood, during the 1980s stylistically ambitious directors in Japan, Taiwan, and China began building scenes out of long, static takes. Sometimes those are distant framings, unfolding in elaborate blocking; to my mind Hou Hsiao-hsien is the great master of this. But no less prominent are those films that present simply staged shots of two or more characters in which action and reaction are captured by a fixed camera. Often these shots avoid 3/4 views. That is, we may get two characters in profile, or two characters facing the camera directly. The result is a more abstract, even ceremonial look and feel.

I was remembering this tendency while watching several of the films on display here at the Vancouver International Film Festival [9]. I saw one film very largely made of two-shots. I saw a couple in which the two-shots serve mostly as points of punctuation, breathing space between scenes that are cut up in more orthodox ways. And I saw one film that climaxed in a two-shot showing the actors holding their ground for about fourteen minutes. All were from Asia.

Both visual and plot-based information follows; in other words, as often happens hereabouts, there are spoilers.

The Return of Kids Return

Kids Return: The Reunion, directed by Shimizu Hiroshi, is a sequel to Kitano Takeshi’s 1996 film. The disaffected high-school buddies Shinji and Masaru were last seen riding a bike and declaring that they would show the world what they’ve got. Now, many years later, they haven’t shown much. Masaru is a low-level gangster who has lost the use of his left arm in a jailhouse brawl. Shinji holds a boring job as a security guard, and he’s about to give up boxing. The two meet by accident and resume a more distant version of their friendship. Masaru gets more deeply embroiled in the yakuza world, but he does convince Shinji to stick with prizefighting. As Shinji struggles to improve his skill, Masaru sets out to avenge his betrayed boss, with murderous results.

The new version doesn’t have the dry, laconic quality of Kids Return, and the film doesn’t employ Kitano’s characteristic planimetric framing and compass-point editing [11]. But the incessant over-the-shoulder framings of most movies are avoided; when we cut to a character, he or she is usually isolated in the frame. And some moments recall the cartoon-panel cutting of Kitano. One scene shifts from the yakuza boss, Masaru, and the thug Yuji in a coffee shop to a soundless shot of their young subordinate at the office simply staring off into space. Cut to the three men strolling back to the office, with Yuji commenting that the kid never keeps the sidewalk clean.

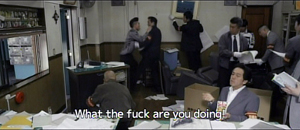

A pan following the men into their building shows the office open and men inside. Yuji bolts past his boss and flings himself at a policeman, who is one of several ransacking the place for evidence.

Most directors wouldn’t include the enigmatic shot of the functionary, but it yields a little question–what is he reacting to?–that the next shots gradually answer.

So cutting plays an important part in building up many scenes. But occasionally Shimizu pauses to draw a moment out. When Murasu and Shinji meet after many years, a nearly thirty-second shot squares them off.

Instead of embracing and pounding each other’s back in the American fashion, they stand awkwardly opposite each other, and the anamorphic widescreen image stresses the tentativeness of their reunion. Later, when Murasu’s boss suggests he leave town and work for another boss, a poised two-shot (at the top of this section) lets us watch the interplay between them across two minutes. Again, the ‘Scope ratio helps, and the fixed frame adds a comic touch by setting at frame center the hideous, ticking clock that Yuji has bought the boss.

I don’t want to suggest that there’s anything particularly radical about Shimizu’s two-shots. Kids Return: The Reunion simply reminds us that a two-shot can usefully vary the film’s pace and lend gravity to moments of character reflection.

Absurdist anatomy

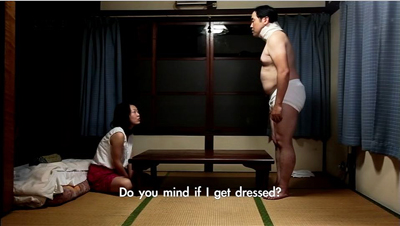

Something stranger goes on in Anatomy of a Paperclip, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers Award [18] here at VIFF. The story is an exercise in grotesque nonsense, a sort of Japanese Theatre of the Absurd.

In an undefined town outside time (no cars, videos, or cellphones), a harsh boss rules over a crude cottage industry. Three, sometimes four, workers sit along a bench and make paper clips by snipping and twisting wire. The most hapless is Kogure, a lumpish loser wearing a neck brace. Bullied by two outlaws who constantly make him surrender his money and take off his clothes, eating with painstaking regularity in the same cheap restaurant, he returns home every night to sleep. A butterfly visits him and apparently leaves a pupa behind. As Kogure trudges through his days of petty humiliations, the pupa swells to human size, even bigger than the pods in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Director Ikeda Akira shot the film in fifteen days over weekends and holidays. It’s partly in the planimetric mode, with the camera lined up perpendicular to a back wall or lines in the setting.

Even more than Kids Return, the mug-shot and police-lineup staging recall linear, minimalist manga. A great deal of the film’s feel, that of a frozen, almost robotic world, derives from this deliberately “flat” look.

In Anatomy of a Paperclip, the profiled two-shot functions as part of the overall visual pattern. Although some conversations show 3/4 views of the characters, and even yield occasional OTS (over-the-shoulder) framings, many two-shots preserve the geometrical right angles of the master shots.

Another function of our two-shot, then: To play its part in a film’s overall pictorial design, suggesting expressive qualities like rigidity, automatism, and deadpan humor.

Two’s company, four’s a crowd

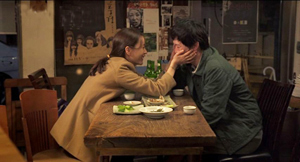

Hong Sangsoo has made the two-shot–usually profiled and showing characters drinking heavily at a restaurant table–into a central formal device. His films are conversation-driven, and he has rung an ingenious series of variations on duologues. They are typically presented in ways that stress similarities and contrasts among characters, often to mildly satiric effect. We see A and B in one setting, then perhaps B and C in another setting, then A and C in the first setting, and so on. For examples, see this entry [24].

In the more formally complex Hong films, these variants may be played out as intermingled points of view (The Power of Kangwon Province) or as alternative versions of the same events (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors) or just weird déja-vu (Turning Gate). In an earlier entry [25], I suggested that Hong exploits our inability to remember certain things precisely, so that we may forget when we first heard a recurring line of dialogue or saw a shot that is echoed by the shot we’re now seeing.

Our Sunhi is about a hugely momentous event that hasn’t, to my knowledge, been dramatized on film before: a professor writing a grad-school recommendation. Sunhi approaches Professor Choi for a reference that will help her study in the States. As she coaxes him into revising his initially cool letter, he becomes attracted to her, as does another university employee Jaehak. Meanwhile Sunhi meets her old lover Munsu, and he becomes attracted to her all over again.

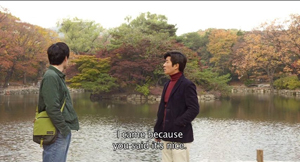

Here the formal rondelay that mocks male vanity–a Hong specialty–doesn’t involve fancy tricks with time or parallel viewpoints.Instead, what circulates are comments about Sunhi, pulled from the professor’s letter (“She has artistic sense,” “She’s honest and brave”) and passed from man to man. The points of circulation come in eleven duologues, each shot in one or two symmetrical long takes. Sunhi meets Jaehak, then Choi, then Jaehak again, then Munsu. Soon Munsu is going out drinking with Jaehak, with whom the prof has coffee before having a rendezvous with Sunhi. Connecting these nodal scenes are brief shots of characters walking through streets, meeting one another by accident, and at the finale, converging in a palace park. As you’d expect, these connecting bits are typically made parallel to each other through framing, situation, music, or other devices.

The two-shots are very long; the longest runs over eleven minutes. It presents a sort of climax, in which a drunken Sunhi reaches out to clutch Jaehak–a gesture of greater intimacy than she has shown any other man.

But soon enough she is meeting the professor for a date in the park. In the very last scene, when she goes off to the toilet, Hong gives us a tiny joke. All three of the men finally meet, waiting for her, and at last a two-shot becomes a three-shot.

This sheerly formal gag is pretty esoteric, I grant you, but it’s typical of Hong’s urge to tweak the simplest materials. In his hands, the lowly two-shot becomes a structuring constraint, a way of deliberately limiting his choices to show us what he can do with it–not least, comic variation.

Two heads, better than one?

During the 1940s, directors in various countries began to rethink the layout of their two-shots. Instead of giving us matching profiled or 3/4 views, they began to arrange their players so that one figure was significantly closer to the camera, yielding what I’ve called a big-foreground composition. In America, the most flamboyant early versions came from Orson Welles (Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons) and William Wyler (The Little Foxes, below). This strategy encouraged staging in depth and even letting players turn their backs to one another.

Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs is the most elliptical and visually variegated film of this VIFF bunch. It’s less a story than a situation: A father, mother, and two children try to survive on the streets. The father picks up odd jobs, while the mother finds work in a supermarket. They wash in public restrooms and scrounge castoff food, sometimes thanks to the mother’s rescuing market goods past their sell-by date. At night, the father and the kids huddle in a makeshift hut, until the mother finds a somewhat better squat in a ruined office building.

Every scene except one consists of a single take, but the connections between scenes are far more oblique than in the other films in this entry. For instance, the mother is seen weeping beside her sleeping children in the opening shot, but then she vanishes from the plot for a while before reappearing in the supermarket, now with her hair cut shorter. The clear and continuous duration of the scenes is offset by a narrative organization that skips over a lot of time and refuses to explain everything that happens in the interim.

Tsai’s visual strategies are quite diverse. Unlike Hong Sangsoo and others in this trend, he doesn’t always keep his camera within a mid-range zone. A scene’s single take can be a striking extreme long-shot or a tight close-up, often of the father (played by the still remarkably waif-like Lee kang-sheng) eating, drinking, or just reciting a poem.

Stray Dogs makes little use of two-shots, and his “clothesline” layouts aren’t quite as frieze-like as those in Anatomy of a Paper Clip.

He saves his devastating two-shot for what is, in this quiet and melancholy drama, as close as we get to an intimate climax. The image at the top of this section shows the husband and wife, her face looming in the foreground while he stands behind her.

Why is this shot, only three minutes longer than one in Our Sunhi, so fiercely hard to take? Hong Sangsoo fills his restaurant shot with gab and plot development. Tsai’s shot, reminiscent of the big-foreground compositions of Welles and Wyler and many afterward, is almost completely unchanging. Neither husband nor wife speaks for fourteen minutes; the only action we see in most of the shot consists of him occasionally swigging alcohol from the bottles he’s stolen and some tears running down her cheek. And we have no idea of when the shot will end because there’s no obvious trajectory set up for it. Like the fixed close-up of a weeping face that ends Tsai’s Vive l’amour, this shot could go on forever.

About thirteen minutes in, the husband grasps his wife’s shoulders and leans his head wearily against her neck.

In a context scoured of what we normally think of as drama, such tiny movements become major events. The father seems at once apologizing for his drinking and trying for a reconciliation.

Tsai has reserved his two-shot for his climax. Instead of becoming a resource judiciously salted through the film (Kids Return: The Reunion) or a stylized extension of a cartoonish world (Anatomy of a Paper Clip) or a core schema for the film’s visual design (Our Sunhi), the two-shot here, rendered as an aggressive image of faces close to the camera, becomes the marker of a mysterious turning point in two lives.

All the films are very much worth seeing for their own reasons. Treating them together, though, reminded me of the power lurking within one very basic cinematic resource.

Last year I considered long-take shooting and staging techniques [36] in that edition of Dragons and Tigers, with comments on Tsai Ming-liang’s Walker.

Just in case this occurred to you: No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent these techniques. This entry [11] and some others [37] explain.

For more on varieties of staging, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, you can visit the supplement to Figures [38] here, and the categories Film Technique: Staging [39]and Tableau Staging [40].

Stray Dogs.