Kristin here:

I didn’t manage to see all the animated films at the Vancouver International Film Festival, but I saw three. That is, I saw two animated features and one documentary about an ambitious and lengthy project that never saw the light of day except in butchered form. The films differ widely in subject and will probably appeal to quite different audiences.

The young

Ernest et Célestine (2012, co-directors Benjamin Renner, Vincent Patar, and Stéphane Aubier) is one of those irresistible cartoons based on a well-loved children’s book series. From 1982 to 2004 , Belgian artist Gabrielle Vincent (1928-2004) created this series, based on the unlikely friendship of a little-girl mouse and an adult bear. The film’s imagery replicates the style of the books’ water-color illustrations (see above). Although the series is not well known in the English-language markets, a few translations [2]have appeared. Most are out of print and apparently very collectible, though there is an English-language volume [3] coming out on November 1. This film version might well foster the popularity of the books internationally.

Bears and mice are here assumed to be dire enemies, a premise set up in the opening as Célestine and her fellow orphans are told a cautionary tale by an elderly lady supervisor. It turns out, however, that mice are Tooth Fairies, and that occasionally involves their visiting bear families to exchange coins for the baby teeth of cubs. Such a mission leads to Célestine visiting a bear family (in the candy shop pictured above) and meeting Ernest, a large bear who vainly attempts to make a living as a street musician. The pair become unlikely friends, and as a result become outcasts living together in Ernest’s cottage in the forest. Eventually each is tried in court for having transgressed the natural boundaries between their species.

Visually the film is charming, though narratively it clearly is intended for small children. Unfortunately the screening I attended had an audience mainly made up of adults, only a few of whom brought children with them. Children accustomed to the break-neck pace of anime and contemporary television cartoons may not have the patience for the calm, leisurely narrative pace in Ernest et Célestine. Young children and those with more appreciation for traditional narratives will delight in it however, and it would be worth seeking it out in art-house screenings and, with luck, in video release. Its message of tolerance and understanding among widely different sorts of “people” is simple but effective.

A book of the art of the film [4], with illustrations by Vincent, is soon to be released in France.

The old

At the opposite end of the age range is Wrinkles (2012, Ignacio Ferreras), a Spanish animated feature about an elderly gentleman, Emilio, whose adult children become fed up with caring for him as he slips into the early stages of Alzheimer’s. They consign him to a slick, soulless care facility and visit him only rarely at holidays. Discouraged and unhappy at first, Emilio gradually comes to appreciate the small pleasures and support the other “clients” at the home can bring each other (see bottom). His roommate, a cynical long-term resident who practices minor con tricks on vulnerable, disoriented neighbors, nevertheless provides humor and support. A still-healthy wife who has nevertheless come to the facility to take care of her husband, an advanced Alzheimer’s patient, shows that love can bring a trace of reaction even from a seemingly unresponsive person.

The story is touching, and the opening provides a surprise moment that conveys Emilio’s encroaching confusion well. The animation, though fairly limited, is well designed and attractive. The endings for the various patients seem to put a distinctly cheerier spin on the grim advance of Alzheimer’s than one would imagine to be appropriate to the subject. Still, the film looks at the subject compassionately and manages several touching scenes.

The ghost

Vancouver was the venue for the world premiere of Kevin Schreck’s documentary, Persistence of Vision (2012). It deals with animator Richard Williams [6], who made a successful career running a studio primarily making animated commercials and credit sequences. Back in the 1980s and 1990s I must have passed it on London’s Soho Square dozens of times completely unawares.) One of Williams’ employees also devised the technique for merging live-action and cartoons that was used for Robert Zemeckis’ Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), and perhaps the best-known achievement of Williams’ studio was the animation in that film.

Schreck does a good job of presenting an overview of Williams’ career, but his real fascination is with the one doomed project that Williams pursued for about twenty-five years: a feature-length, absurdly technically complex feature to be called The Thief and the Cobbler. The scene above showing one of the characters performing an elaborate card trick is dazzling to behold. It takes place against a neutral background, but a battle scene, a substantial portion of which is shown in Persistence of Vision, goes much further, combining dizzying shifts through convoluted settings with mind-boggling movements of figures.

Williams’ studio worked on the film from 1964 to 1992, but only part-time, fitting it in among their various commissions. Schreck has tracked down several of the main animators who worked for Williams during substantial stretches of this period, and they give invaluable information about what became a legendary epic. Williams refused to participate, but there is quite a bit of historical documentary footage of him. Much of the original material from the film was destroyed, but Schreck, often with the help of his interviewees and others, tracked down original material in various degrees of completion. Several shivery animated sequences consisting of simple pencil tests are included, as are other scenes in later stages of animation. The result is a precious glimpse into the film that might have been.

Ultimately Warner Bros. committed to finance and release the film. This might possibly have worked, but by one piece of misfortune, design elements for The Thief and the Cobbler made their way to Disney and were, putatively (and plausibly) used for the Genie and other components of Aladdin (1992). This was a blow to the commercial viability of Williams’ film. That, in combination with Williams’ failure to complete it by the contractual deadline meant that The Thief and the Cobbler was turned over to a completion insurer. Somehow (in a deal not explained in Persistence of Vision), Miramax ended up with the project. They stitched together the existing sequences using new footage, including Disney-style musical numbers, something that Williams had been determined to avoid. In 1993 Miramax released a highly revised version of The Thief and the Cobbler. [7]

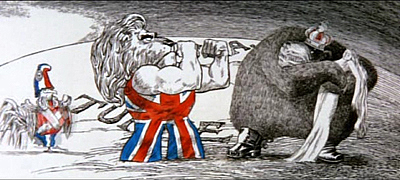

Williams seems to have been one of those artists who works best when kept on a very tight leash. The man was brilliant when it came to making TV commercials, some of which are shown in Persistence of Vision. He created some memorable credits sequences, also shown. I vividly remember seeing Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1968. That was two years before I took my first film course, but even then I realized that the credits were better than the film they graced:

Williams did some of the late Pink Panther ones, too. Clearly, given a short, immutable length, he could come up with a gem. Similarly, when he worked as a collaborator on another director’s film, as with Roger Rabbit, he apparently didn’t become overly ambitious and unrealistic in his goals. It was apparently this one mad vision that slowly drew him to overstep the bounds of feasibility.

Williams’ legacy will not rest simply in these credit sequences and ads. Nor will it reside only in the images in Persistence of Vision, ranging from jumpy pencil tests to semi-finished sequences (and the sequences included in the unfortunate Miramax version). Williams wrote a book, The Animator’s Survival Kit, initially published in 2002, and, coincidentally, released in an expanded edition [9] just last month. It is considered one of the basis books in the field and is used by amateurs and pros alike. Williams discusses the new edition in a brief clip [10], and one can see his sincere enthusiasm and also his restless energy. He also gives master-classes in animation.

Whether Williams could ever have created a narrative structure to pull together the brilliant set-pieces on display in Persistence of Vision is another question. Clearly his colleagues still regard him with a mix of admiration, devotion, and exasperation. Schreck’s film hints at a masterpiece that was mutilated and yet also suggests that the masterpiece itself was a elusive vision that was problematic from the start.

[11]We enjoyed meeting Kevin and line producer Sarah Timberlake Taylor at the festival. During the introduction to the second of three screenings, Kevin expressed his surprise at the fact that the first and second screenings were both better attended than he expected. From the Q & A, I gathered that the audience included some animation buffs well acquainted with Williams’ career. The Thief and the Cobbler is clearly well known in the world of academic animation history. Buffs will be delighted that Schreck has pulled together so much material and given us as full a look at this lost film, masterpiece or not, as we are ever likely to have.

[11]We enjoyed meeting Kevin and line producer Sarah Timberlake Taylor at the festival. During the introduction to the second of three screenings, Kevin expressed his surprise at the fact that the first and second screenings were both better attended than he expected. From the Q & A, I gathered that the audience included some animation buffs well acquainted with Williams’ career. The Thief and the Cobbler is clearly well known in the world of academic animation history. Buffs will be delighted that Schreck has pulled together so much material and given us as full a look at this lost film, masterpiece or not, as we are ever likely to have.

One problem that Kevin explained is that he cannot release the film into theaters (or presumably on DVD or VOD). It contains extensive clips of copyrighted material, including the various credits sequences and ads by Williams’ studio, short segments from Aladdin and other Hollywood films, as well as The Thief and the Cobbler in its version released by Miramax. This seems a tremendous pity. Given the historical and critical nature of Kevin’s film, it seems possible that such clips could be justified as fair use.

Much has been made of Room 237, the analytical documentary about Kubrick’s The Shining, which was also shown at Vancouver and other festivals. It has a theatrical release in the USA through IFC. Apparently no permissions were obtained from the owners of the copyrights for The Shining and other Kubrick films excerpted in the documentary, with fair use being claimed [12]. As usual, no court cases have so far been filed, and so it is not clear whether fair use actually applies to such extensive uses of clips in historical and analytical studies. Persistence of Vision seems another clear-cut case of fair use, and it would be encouraging to see a distributor courageous enough to release it outside the festival circuit without “permissions” being sought.

October 21: David Cairns has kindly written to point out that there is an epic fan edit [13] of the original footage of The Thief and the Cobbler. It’s incomplete, of course, but it’s 96 minutes long–and obviously a labor of love on the part of Garrett Gilchrist.