Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger [2]is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay [3]celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema [4]. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet [5]. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film [6], as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation [7] (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege [8], which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours [9], called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman [10] updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun [11] (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage [13] is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course [14], “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

[15]As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

[15]As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky [16]. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint [17] as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

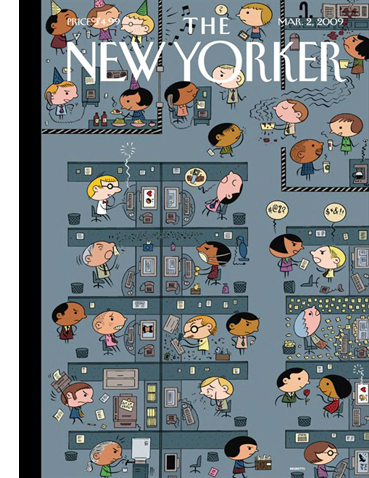

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” [18] page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin [19]. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen [20] and the now-departed Capital City [21] comics distribution firm. (DB)

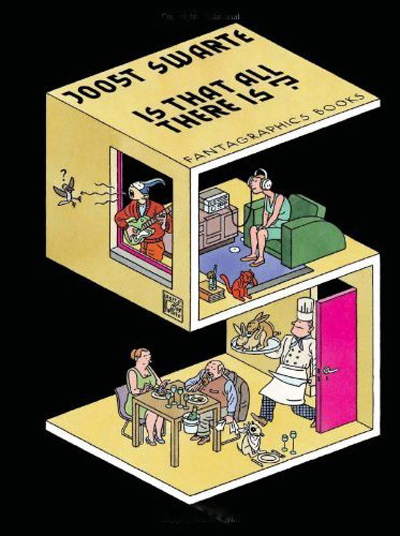

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here [23] and here [24] and here [25]); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is? [26]

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here [28] and here [29], in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack [30] of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist [31], a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits [32] in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez [33] of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus [34]. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation [35].

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration [36]. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here [37]. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here [38].

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here [39].

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.