A video-wall display in the Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

DB here:

You’re in a multiplex. The pre-show attractions are large, loud promotions for TV shows, pop music, and star careers, interspersed with ads for men’s cologne and local pet-grooming facilities. Then comes the theatre chain itself telling you to hush up, turn off anything that emits light or sound, take your feet off the seats in front of you, and buy some popcorn. Next comes a barrage of trailers. Sooner or later the movie starts.

If you look back at the projection booth, will you see another human being? Not necessarily. It’s possible that everything that happens in your theatre is automated.

Now imagine another space, a large room with ranks of work stations. A couple of dozen people sit before their monitors, facing a video wall. From a room like this in Omaha, Nebraska, or in Cypress, California, or in Liège, Belgium, or in Shenzhen, China, these workers can remotely track thousands of theatre screens, including yours. It’s another consequence of the emergence of digital projection in our movie theatres.

Command and control

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre, 1948, from the splendor that is Cinema Treasures [3].

One of the many lessons you learn from Douglas Gomery’s magisterial history of the Hollywood studio system [4] is straightforward. For about a hundred years, film producers and distributors have sought to control exhibition.

The advantages are obvious. Controlling exhibition keeps competitors off screens, it yields more or less assured revenues, and it allows vast economies of scale. If you can count on 2000-4000 screens playing your movie, as is common for Hollywood releases today, you can budget your production accordingly.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, studio control was quite direct. The Big Five companies (Paramount, Loew’s/MGM, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO) wholly or partially owned hundreds of theatres, and these served as display cases for their product. Because no studio could supply all its theatre chains with films, studios shared their screens with their peers and kept other companies’ films out. “Here,” Gomery writes, “was a collusive oligopoly (control by a few) that operated as an almost pure monopoly.”

The studios didn’t own most of America’s theatres, just the most profitable ones. The thousands of independent houses and chains were subjected to studio control in more indirect ways. The studios forced the independents to book films in batches (“blocks”). To get prime releases, the exhibitors had to take weaker titles. Likewise, the independents had to bid for upcoming releases without being able to see them.

The structure of the market was another strategy of control. Adolph Zukor pioneered the system of runs, zones, and clearances. If people wanted to see a new release immediately, they had to pay top dollar at a first-run theatre. After a certain interval, the clearance, the movie would play a second run theatre in another territory at a lower price, and so on down the food chain of movie houses.

Technology was another strategy of control. The 35mm film standard wasn’t proprietary, but the sound systems that the studios adopted in the late 1920s were. Of the dozens of systems, only two became standardized: Western Electric and RCA. In a process similar to what’s happening today, theatres were forced to install one system or the other. The thousands of screens that couldn’t afford the new technology went dark.

This system worked to the Big Five’s benefit until 1948, when the Supreme Court declared Hollywood’s vertical integration monopolistic. The studios chose the wisest way to break up, given the slump in admissions: They divested themselves of their theatres and concentrated on production and distribution. (The process took several years in some cases, and there often remained close unofficial ties between the Majors and their former circuits.) In addition, block-booking and blind bidding were outlawed, so some market factors became more favorable to exhibitors.

The postwar studios occasionally tried to remake exhibition through new technology. CinemaScope, designed by 20th Century-Fox, sought to become the industry standard for widescreen presentation. Although there was considerable take-up, it had competition from other systems (notably Paramount’s VistaVision) and exhibitors were able to wring concessions from Fox. Centrally, exhibitors were reluctant to install magnetic stereo playback, and so Fox had to compromise by producing prints that could play on optical sound systems as well. Similarly, while various 70mm formats were tried, none became obligatory for exhibitors, since films released in 70 were also released in 35, if only in later runs.

Of course Hollywood still had a desirable product and could charge dearly for it, so stiff contracts for revenue returns gave studios considerable power. In the 1970s, the Majors (which no longer included RKO and had expanded to include Disney, Columbia, and Universal) found another way to use market dynamics to control exhibition. To publicize Jaws (1975), Universal launched massive television advertising and avoided the “platforming” or “exclusive engagement” practice. Studio chief Lew Wasserman opted for “saturation booking,” releasing Jaws on over 400 screens simultaneously. A month later it expanded to over 600.

The growth of the blockbuster, nurtured by Star Wars, Superman, and other huge hits, encouraged theatre chains to build multiplexes. The distributors could then blanket screens with their product. Exhibitors could realize economies of scale by holding over some movies for months while rotating regular releases through other screens.

With the arrival of cable, satellite transmission, and home video, studios were able to maintain tiers of price discrimination. The theatrical opening became the loss-leader, making less revenues but establishing buzz for the ancillary market. Theatrical runs were shortened considerably, but the “windows” of video distribution became the equivalent of second- and later runs. A movie becomes available on Pay Per View, then VOD and/or DVD, then premium cable, and so on. The windows’ length and ordering have changed over the years, but throughout, by carving up the market by price discrimination the studios continued to rule exhibition patterns.

My account makes recent history too neat, with studios apparently steamrollering unprotesting exhibitors. In fact, exhibitors have responded to some pressures by dragging their feet or pushing back. Better sound systems took some years to penetrate the market. Some big theatres refused to play Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace because of onerous terms, including a minimum guarantee and a commitment to a lengthy run in a ‘plex’s biggest auditorium. More recently, studios’ efforts to shorten windows and release films sooner on DVD [5] or on VOD [6] have sparked resistance.

Studios have periodically tried to become vertically integrated again. There were some attempts in the 1980s to run theatre circuits, but only Viacom has found success owning both Paramount and the National Amusements chain. Today, technology is providing a more effective lever–or rather a crowbar. Digital projection furnishes the most thoroughgoing opportunity for studio control over exhibition since the coming of sound, and perhaps since the days when the Majors owned movie houses.

NOC, NOC, who’s there?

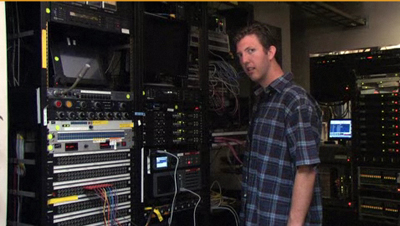

Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

My first entry in this series [8] considered the power of setting standards, something Hollywood has been good at for decades. In 2005 the Majors established the technical specifications for the Digital Cinema Initiatives. As has happened throughout history, they had the input from the powerful manufacturers, service companies, and professional associations, like the SMPTE and the American Society of Cinematographers.

Once the standards were set, the projection and service suppliers could move forward with appropriate equipment. The conversion is expensive, so exhibitors have been offered the option of signing up for a Virtual Print Fee. This is a partial subsidy from the major companies that is passed through an “integrator,” a third-party company that attends to acquiring the equipment, installing it, and monitoring payback.

A decade ago, over a dozen significant US theatre chains filed for bankruptcy protection, so costs are constantly on exhibitors’ minds. Digital projection offered multiplex operators the opportunity to cut staff. Screening film prints is somewhat technical, and it relies on mechanical skills that are growing rare. So anything the manager can do to simplify running the show is welcome. Movies on digital files filled the bill. A film projectionist, represented by what was once one of the more powerful unions around, is expensive. Teenage labor is not.

Digital works for the fresh-faced novice. Once the film comes in on a hard drive, it’s not terribly hard to set up a show. Disney has made a couple of remarkable instructional films (here [9] and here [10]) for the new projector operator Jimmy, who wears the requisite Bob & Ted apparel.

In the old days, Walt would have given us a cartoon, and Goofy would have been the star.

Jimmy loads the movies, and he or the manager sets up the programs. Once the features, the trailers, and the ads are on the servers or the library system, the theatre manager can program every screen. From a computer in the manager’s office, or almost anywhere, he or she can build each auditorium’s playlist by dragging and dropping. If the arrangements with the distributor permit, the files can be migrated from screen to screen.

Even under these conditions, though, you need minimal maintenance. Projector lamps must be changed, for instance. The installers or a local expert can supply routine maintenance, but sometimes there are problems. An encrypted file can’t be opened, or it’s corrupted, or the show mysteriously stops. Very likely Jimmy, even consulting his manual, can’t fix the problem.

Enter the NOC.

Network Operations Centers, also known as Data Centers, are part of broader Information Technology management. They’re used whenever a business or government agency has a network that needs 24/7 monitoring. All Fortune 1000 companies have NOCs, and probably have mirror backups of them scattered around the world. NOCs coordinate railway systems, military systems, banking, and police and fire departments. Amazon has a NOC in Seattle, Wal-Mart has one in Bentonville, Arkansas, and AT&T has a monstrous one in Bedminster, New Jersey (below).

There’s a nice gallery of NOCs here [13].

Don’t confuse NOCs with call centers or help lines. NOCs are handling and storing vast streams of data from computers, cameras, and other inputs. The goal is keeping track of things pertinent to the business or agency. But of course even large staffs can’t do this simply by eyeballing the flood of data. Instead, the software is set to notice anomalies and to call them to the attention of the humans. So if a police camera outside a Tube stop in London picks up a pattern of unusual activity, say three men running purposefully toward a woman, that information is pulled out of the stream and sent to an operator for inspection.

Once film theatres became digital, they acquired the ability to connect to NOCs via the Web. An owner who funded the purchase of the DCI-compliant equipment might well choose to pay a NOC to provide oversight and help. Exhibitors who sign up for a Virtual Print Fee program are required to sign up for a NOC. NOC services may be supplied by the equipment manufacturer (Sony [14], Christie’s [15], Barco [16], GDC [17] et al.) or by the installer, such as Ballantyne Strong [18] (Omaha) or Film-Tech Cinema Systems [19] (Plano, Texas). An integrator may also offer NOC services, as Cinedigm [20] does in the US and XDC [21] does in Europe.

By the standards of giants like AT&T, a theatre-monitoring NOC tends to be fairly small, as my pictures indicate. Still, the purpose is the same. Each projector/ server combination and theatre-management system (essentially a master server) is connected via the internet to the NOC. The NOC monitors the state of the system, so that, for instance, it can keep track of lamp life, parts conditions, net connectivity, and the like. The software can send alerts to the theatre management for upcoming maintenance and can do troubleshooting. It’s also trained to notice problems—glitches in playback, lights going on, dropped subtitles, or whatever. Anomalies are called to the attention of the specialists at the work stations.

The projector manufacturer Christie’s initiated one of the first NOCs in 2003, and it now monitors over 3700 digital screens across the US and Canada. From its California facility [22] it “manages the configuration of systems, provides help-desk services to customer staff, and access to local technicians with local parts to provide on-site repair and support.” The Shenzhen center maintained by GDC, a server company, monitors ten thousand screens [17]. Most NOCs don’t plan programming or chase down encryption keys from distributors, but the NOC maintained by Film-Tech will perform these services as well. It will even power up and down the auditorium. With the Film-Tech system in place, says the company’s brochure [23], “The projection booth can literally operate for months without anyone ever entering it.”

The show must go on, if remotely

The projection area of the Studio Movie Grill City Centre, Houston [25], announced as the world’s first completely automated booth.

Now Jimmy and his manager have substantial support, but in turn they’ve shared a lot of information with the NOC. In order to collect the Virtual Print Fee, the exhibitor must play the studio’s film on a contractual basis—for a certain period, a certain number of times per day, and so on.

In earlier times, a dodgy exhibitor might run a film more frequently than was reported back to the distributor, with the exhibitor pocketing the difference. Or an exhibitor might trim shows of a poorly performing title, substituting something more popular and depriving the weak film of playing slots and box-office payback. In the pre-digital days, distributors sent out “checkers,” staff disguised as ordinary moviegoers, to see that theatres were running films according to the booking.

Now the projector/server mating provides real-time screening information to the NOC, and that flows to the distributor. Says an executive at a firm supplying NOC services:

All of the NOCs notify the studios about the performance of the systems. Uptime is critical or VPFs will not be paid. Exhibitors cannot miss more than a certain number of allotted shows and still receive their checks. . . . All NOCs provide the studios with access to the playback logs to ensure the movies booked are actually played.

According to the same source, some NOC systems monitor the use of the equipment outside normal shows. “Some of the traditional NOCs go so far as to ensure the equipment is not used for anything else, and the theatre will be back-charged for the use of that equipment.”

At a minimum, then, the performance information forces the exhibitor to abide by the booking contract. But it also means that even with full knowledge on the part of both exhibitor and distributor, the advantage lies with the distributor.

For example, if an exhibitor wants to play a film from outside the Majors, even if that film is available on a DCI-compliant file, that distributor has to pay a VPF. From the standpoint of the studios and the supply companies, he who pays the piper calls the tune: A DCI-compliant projector shouldn’t be used by free riders who didn’t participate in the DCI. Why should the Big Six establish the standard and fund the purchase and installation of the gear in order to play a competitor’s film? If the exhibitor dares to proceed without the VPF and uses the equipment to show unauthorized product, that information flows back to the NOC.

Consider as well the practice of “splitting.” Smaller theatres and art houses often adopt the multiplex tactic of offering many titles, but for them that entails showing two or more films on the same screen in a given day. Often splitting is done with the advance permission of the distributor, but sometimes it’s done ad hoc and reported after the fact (unlike the dodgy practice of show-shuffling I mentioned above). But VPF conditions may forbid splitting altogether. And if the exhibitor is obliged to do it, as when one movie file fails to run and another must replace it, the NOC will flag it.

Distributors allow a certain leeway for quality checks, running a film at odd hours to make sure it plays properly. Still, the NOC is tuned to those anomalies too. One exhibitor remarks, “If I’m demoing a movie, they may not know it’s a demo. They might wonder why I played a movie at 9:30 AM.”

In a highly automated environment, things can proceed blindly. There’s a story (not apocryphal, I think) about an early automated theatre system here in Madison, Wisconsin. During the 1970s, a snowstorm paralyzed the town, but someone at a theatre had left the system on. Even though the theatre was closed (and no one could get to it), the show went on: lights up, lights down, curtain parts, film runs, film halts, lights up, film rewinds….

More vaguely, some exhibitors worry about the NOC as a policing or surveillance operation. No one can object to a mechanism that enforces contracts, but film screenings have long had a certain fluidity, especially in the art-house realm. On-the-fly compromises and flexible arrangements emerged from negotiations among managers, programmers, bookers, and distribution staff. People knew one another and made allowances for specific circumstances. When so much of scheduling and operation is transferred to servers, playlists, and NOCs, human contact is likely to wane. The projectionist isn’t the only ghost haunting the multiplex.

Anyone who has ordered something with a credit card online has already submitted to the oversight of a NOC. But when your livelihood depends on smoothly functioning film screenings, you could be understandably apprehensive about turning your business over to unknown others in unknown places. Hacking, malware, and human error are spectres hovering over all of IT. As one theatre owner told me: “[The NOC] could shut off every theatre at one time and in the process send a little message, like the Jolly Roger in Independence Day when the guys bugged the mother ship.”

The studios innovated technology and had the power to set standards and restructure the flow of product. The multiplex exhibitors wanted to cut costs and simplify presentation. This meshing of interests allowed Hollywood studios to control exhibition to a new degree. Who wants to own theatres anyway? They entangle you in mortgages and real estate crises, and they have the awkward habit of going into bankruptcy. In addition, the Majors could win over local exhibitors by upcharging for 3D and by supplying ad packages that generate more income. Today if you control the files, the encryption, and the network, you control the show.

What’s left for the managers? Well, there’s selling popcorn.

This is the seventh in a series of entries [26] on the conversion to digital projection in cinemas.

Thanks to Douglas Gomery, whose work on the American film industry has guided my thinking for the years going back to our teaching together at Madison in 1973. The place to start is his superb book The Hollywood Studio System: A History, which is complemented by his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States [27]. I’m grateful as well to those exhibitors and service specialists willing to share information with me, as well as to Jenn Jennings, who is making a film about the digital transition, and Jim Cortada [28] of IBM and the Irvington Way Institute.

The Film-Tech Forum [29] is an informative chatroom concerning projection and general film matters. Examples of NOCs in action have been provided in videos by Christie [30] and XDC [31]. In the latter, and true to European sophistication, our fashion-challenged Jimmy is replaced by a woman with bangs and a discreet nose ring. Yet like you and me, she likes a snack.