Archive for December 2011

A modest extravagance: Four looks at Ozu

DB here:

Ozu Yasujiro was born on 12 December 1903. He died on 12 December 1963.

For Donald Richie

The film comes to us calmly, not trying to overpower us or sneak into our good graces: just a simple story that seems to tell itself. First there is the daily routine. People arise, go to work or school, greet their acquaintances, labor at their desks, meet friends at a bar or teahouse or coffeehouse. Gradually, as one character mentions or meets another, the film carries us to that one. Then we discover another network of people, also linked through everyday action and little courtesies. This movie, it seems, could sidestep from group to group forever, eventually introducing us to the population of Japan.

A plot coalesces. Someone has fallen in love; someone is unhappy; someone must pass an exam; someone must get married to oblige a parent. Now everything that we have seen starts to crystallize into a drama. But the narrative flow is so unpredictable, even diffuse, that we can scarcely imagine what the climax could be. Sometimes the action is just put on hold, and an idyll shows a character recalling days of prior happiness, or imagining recalling today as a moment of consummate peace.

Suddenly a crisis descends. Someone we have come to care about falls ill, or decides not to marry, or decides to marry someone else, or betrays a friend. And soon we are truly overpowered, with a climax that seems completely contingent. Why this? Why now? The characters may ask along with us, but they resign themselves to things. The epilogue is like a farewell. These people who have come to matter to us drift away to an uncertain future that has a touch of stoic serenity.

All very straightforward, even artless. But that’s at first glance. Take a second look, and you see a subtle architecture. The distantly connected characters actually form a table of contrasts. For every wilful father, a tolerant one; for every cheerful daughter, a morose one; for each flirtatious boss a kindly widower. Long ago Donald Richie pointed out the importance of parallelism in Ozu: every person or circumstance is echoed or inverted elsewhere. Into these parallels Ozu inserts prefigurations of future action, motifs which connect characters (gestures, lines of dialogue, props like watches or cups), and daring ellipses which skip over important events. (Once he has us hooked, he can tease us by withholding what we want to see.) The ending and epilogue have the inevitability of the final lines of a grand poem. Look closely, and each Ozu film has a magnificently filigreed structure, and everything that will happen seems quietly destined from the start.

Third look: The simplicity of style. What could be easier than to shoot each scene with a master shot, followed by medium-shots? Each character, no matter how minor, gets his or her “single,” and a cut very seldom interrupts a line of dialogue. Every person gets a chance to speak, and people listen to each other. Nobody interrupts. A few establishing shots will link one scene with another. The camera is set low in nearly every shot, as if to eliminate any decision about where else it might be put, and it almost never moves. This, surely, is Moviemaking 101.

Look again, and it all becomes staggeringly complicated. Each shot is composed meticulously, down to the arrangement of food on the table. The compositions mirror each other uncannily: every medium-shot single puts the person’s face in the same part of the frame, so that the eyes of one character weirdly coincide with those of another. Indeed, Ozu’s bold play with graphic qualities—lines, masses, and color—from shot to shot is without peer in mainstream filmmaking. Contrary to what critics still say, the camera position doesn’t mimic a seated person’s view. It’s obstinately low even in train corridors and on sidewalks. What it does is subject the entire visible world to a precise patterning.

Thanks to this maniacally repeated framing, layers of space bristle with tantalizing possibilities. A humdrum space becomes charged with muted dynamism. Mundane bits of setting, like a red teakettle or a hanging sock-tree, come alive. And the intermediate spaces which link scenes often don’t establish the new scene’s locale very clearly. Instead, they hook one area to another by visual or auditory rhymes. The transitions also play games with our expectations. We may think we are going one place, but something, perhaps only the shadow of rippling water cast on a screen, swerves us to somewhere else. Just as Shakespeare’s dialogue can be read as pure poetry, the surface texture of these films would entrance us even if there were no story to follow.

Thanks to his apparently simple stories and easily grasped technique, Ozu has captivated and moved audiences for eighty years. But this humble artisan who compared himself to a tofu seller created a cinema of which no other director dreamed. Modest in effect yet extravagantly precise in execution, Ozu’s films are at once amusing, rapturous, and experimental. He tests his characters, his medium, his audience, and himself. His films show us how profound a genre- and star-driven studio picture can be. At the same time they open up a vast realm of purely cinematic possibilities. No filmmaker has come closer to perfection.

This essay originally appeared in slightly different form in Ozu Yasujiro: 100th Anniversary (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2003). It is reprinted here by permission. Illustrations are from 35mm prints of Equinox Flower, Dragnet Girl, The Lady and the Beard, and Early Summer. DVD copies of Ozu films are available from the Criterion Collection in the US, the British Film Institute in the UK, and other sources elsewhere. A site showcasing all things Ozu is Ozu-san.com. My book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is out of print in hard copy, but a free pdf file is available for download here.

HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to Georges Méliès

Kristin here:

This is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Georges Méliès (1861-1938). I doubt that the release of Hugo was timed to coincide with the occasion. If it were, no doubt the press kits issued by Paramount would have stressed the fact. Still, it’s a happy coincidence.

Hugo is receiving a lot of press attention, not surprisingly. If you’ve read more than one or two of the reviews and articles about Martin Scorsese and his film, you already know the two main hooks that journalists have hung them on. (Whether these originate from the pressbook or are just so darned obvious that everyone can figure them out, I don’t know.)

One, Scorsese is passionate about film history and preservation, so Brian Selznick’s best-seller quasi-graphic novel for children, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, based on the old age of early director George Méliès, would be a natural source for him to adapt. Especially so, since Selznick designed the illustration-heavy book to imitate a film, with series of drawings suggesting camera movements.

Two, the subject of Méliès’ pioneering special effects in the service of fantasy would be the perfect vehicle for Scorsese’s first venture into 3D.

True, no doubt, both of those points, and necessary to ease viewers with no knowledge of film history into this fairly sophisticated film. Not that the critics provide much help with the film’s many allusions to Parisian culture of the first decades of the twentieth century. There are real popular songs and posters for many silent films. I didn’t see any reviews pointing out that James Joyce and Salvador Dalí can be glimpsed fleetingly in Madame Emile’s café. (I spotted Joyce but not Dalí, only learning of the latter’s presence from the credits.)

Apart from signalling such references, however, there is a great deal more that one can say about the film. Some aspects of it are obvious, as befits a movie made in part for children. Others are more subtle, as befits a movie made in part for adults. I’ll offer a few observations here.

By the way, reviewers have made much of the idea that Hugo is not really for children, who would be bored and perhaps frightened by it. I suspect that children under about the age of 10 would be, but older children and teenagers, especially those who read books, should be intrigued by and enjoy it. Like Pixar films or The Simpsons, it’s the sort of thing that can be enjoyed by adults as well as children.

Movies within movies

Hugo is centered around Méliès’ work and tries to recreate something of the magic of the making and viewing of these films. Yet beyond this, it is steeped in the forms and subjects of pre-World War I cinema in general, to the point where the plotlines of Hugo subtly imitate early films.

A turning point in Hugo‘s story comes when Hugo and Isabelle invite fictitious film historian René Tabard (whose name is borrowed from the popular, Chaplin-impersonating teacher young student in Zero for  Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

In the book, the station’s Inspector, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, is a minor figure, glimpsed once from a distance by Hugo and finally coming to threaten him with arrest on page 412. His war wound and early life as an orphan are not part of his character. The Inspector is abetted by the café owner Madame Emile and the newsstand proprietor Monsieur Frick, sinister figures who appear only in this single late scene. They exist primarily to reveal the news of the discovery of the corpse of Hugo’s drunken uncle and to bear witness to Hugo’s thefts of croissants and milk from the café. The flower-shop girl, Lisette, whom the Inspector clumsily courts in the film, is not in the book at all.

What Scorsese very cleverly does is to expand these characters and have them play out what are in effect two brief narratives that could easily be imagined as early silent shorts. Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour) and Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) are transformed from nasty busybodies into a charmingly comic elderly couple whose tentative flirtation is thwarted by Emile’s aggressive dachshund. In two scenes, the dog bites Frick, once on the finger and once on the ankle. In the third scene, Frick solves the problem by providing a lady dachshund to divert the pesky pooch’s attention. One could easily imagine this as a short film from around 1906, making these two the leads and concentrating on their courtship. The dog could thwart the news-vendor’s approaches a few times before the happy ending is achieved with the introduction of the second dog.

The overbearing Inspector’s romance with Lisette is developed at greater length, and one could imagine it as a one- or even a two-reeler of the early 1910s. The Inspector’s attempts to court the young lady could be contrasted with his chivvying of the pathetic young orphan, actions that make her reject his advances. At the end, she might witness him relenting and treating the boy kindly, as indeed happens in Hugo, leading to another happy romantic conclusion.

In general, the situations and characters that we encounter in Hugo are common in early cinema. How many films, especially French ones, involve gendarmerie with their round, flat-topped caps, chasing mischievous little boys? How many melodramas revolve around poor children made homeless by their parents’ or guardians’ drunkenness? How many gags involve men stepping on musical instruments and smashing them? While the most explicit cinematic reference is to the Harold Lloyd feature Safety  Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

In a sense there are little topical and instructional films as well, with the reference to the dramatic historic accident at the Gare du Montparnasse on October 22, 1895, when a train crashed through its buffers and out the front wall of the station. (In reality, one death occurred: the wife of a news vendor who was minding the shop for her husband. Perhaps the Emile-Frick romance creates a happy ending of the cinematic variety to make up for that tragedy.) We also have the lesson in cinema history provided by Tabard. At one point in the flashback narrated by Méliès, apparent newsreel footage of World War I troops, touched up with hand-coloring, appears.

The film-like subplots all end happily, yet they are represented as being reality within Hugo. Perhaps for that reason, none of these brief narratives is the sort that Méliès would have used in his own films. They’re more like the non-fantastical comedies and chases made by Louis Feuillade and other directors.

The happy ending for Méliès occurs in Scorsese’s film, and yet it also happened in reality, if not quite the way it is shown here.

Cruelty, kindness, and the shape of the story

The structure of the narrative reflects the simplicity of each short film. It conforms well to the four-part narrative structure that I have claimed to be conventional practice in classical storytelling. Yet it also breaks neatly into two halves, the first about cruelty and the second about the sort of kindness that makes possible the happy endings. One can picture it as a V shape, with Hugo descending into greater loneliness and danger up to the mid-point and then climbing back toward happiness with the help of others.

Early on, both fate and other people are cruel. A museum fire has killed Hugo’s father, and his mother had earlier died of unspecified causes. Hugo’s drunken uncle wrests him from his home and school to live a fugitive life in the station. “Papa Georges,” whose full identity we do not learn until well into the film, seems unnecessarily harsh with the young Hugo. The Inspector obsessively hunts down stray children to send off to the orphanage. The bookseller Labisse, though generous in loaning books to Hugo’s friend Isabelle, looks upon Hugo with disdain. Even the two dogs, Madame Emile’s comic dachshund and the Inspector’s doberman are growling, threatening beasts.

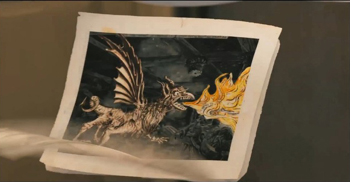

The automaton, of course, is the key to all. Once it provides the necessary clue by drawing the  famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

Ordinarily at this point in a Hollywood film, there would come a section where the protagonist struggles against obstacles to achieve his goal. In Hugo, however, the crisis at the center leads immediately to a series of kind actions. Upon returning to the station after the drawings discovery, Hugo runs into M. Labisse, who unexpectedly gives him a book that the boy and his father had read together. Then Madame Emile urges the Inspector to speak to Lisette, whom he has admired from afar, and coaches him in how to smile pleasantly. His smile, plus his halting success in his first conversation with Lisette, motivate his eventual ability to take pity on Hugo.

This scene leads directly to the scene at the “Film Academy Library” (a giant fictitious room full, apparently, of books on cinema) where the film historian and Méliès fan, René Tabard, appears. He will provide the screening of A Trip to the Moon which finally draws Méliès out of his depression to some degree. Yet the filmmaker still despairs as he thinks of the disappearance of his studio, the rest of his prints, and his beloved automaton. Hugo rushes off to fetch the latter, and after an extended chase sequence returns it to Méliès with the help of the Inspector, who saves the machine and the boy from an oncoming train. Recognizing something of his own youth in the distraught boy, the Inspector turns him over to Méliès for the happy ending.

The exception to the cruelty/kindess division of the film is Isabelle. In the original book she is not such a pleasant character, often arguing with Hugo. She does not have the joyous desire for adventure that the Isabelle of the film displays. The change is an improvement. In part this is because Hugo is such a very grim and forlorn character through much of the book. Portraying him that way in the visual medium of film might make his plight too pathetic to be entertaining. Isabelle’s early sympathy for him and fascination with the mystery of the automaton carries a strong thread of hope across both halves of the narrative.

In the lengthy epilogue there is a gala screening of some recovered Méliès prints, and a party is held. All the significant characters are present, with their satisfactory futures assured. Hugo will seemingly become a magician (as he does in the book). Isabelle has apparently found her hoped-for purpose in life, for she starts writing down the story that we have just witnessed. (In the novel, Hugo himself writes The Invention of Hugo Cabret, though he attributes it to the automaton.)

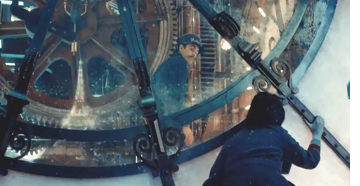

A machine-made ending

The film ends with a tracking shot, independent of the characters’ points-of-view, into a nearby room where the automaton sits, still and alone. As we approach its enigmatic face, the image fades out. The moment ends the imagery that has continued through the film, of humans as machines and  machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

The machine imagery goes further. The opening of the film dissolves from a set of moving clock gears to merge them graphically into a high view of the boulevards of Paris, which momentarily appears as a giant glowing, whirling machine with the Eifel Tower, symbol of the modern machine aesthetic, at its center. The repair of a wind-up mouse becomes the first small point of emotional contact between Méliès and Hugo. The Cinématographe camera/projector that fascinates Méliès even more than the moving images on the screen becomes the central machine, one which produces what one normally thinks of as the most private and mental of events, dreams.

All this machine imagery is fairly obvious, but it seems completely appropriate if we remember that this is, after all, a film partly for children. What I’ve been describing are things that a smart child could grasp, but the imagery and story aren’t done in anything like a condescending way.

The automaton, by the way, really did the drawing in the film itself, without CGI or other sorts of animation being used. For a three-minute film that ends with a fast-motion demonstration of its drawing capabilities, see here. For a demonstration of the restored Maillardet automaton in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, which Selznick used as his inspiration, see here, where it creates a drawing as complex as the one in the film. This automaton also revealed its origins when, after being restored, it signed its maker’s name.

[Dec 9: My claim that the automaton did the drawing without special effects was based on some statements by the company that made it (or more specifically, 15 versions of it). A recent article here interviews the film’s visual-effects supervisor Rob Legato reveals that the drawing scene was accomplished using magnets below the table: “The robot or automaton was not CG, although there were some CG doubles for some complex shots such as the train line fall. Prop builder Dick George constructed 15 automaton versions and some that actually could draw on paper. The VFX and special effects team solved the complex task by using magnets. Below the paper was a motion controlled magnetic system that traced the hand encoded drawing. The arm then moved to match the magnets and draw the famous picture. In a couple of shots if you could pause and really study the frame you might see that the pen nib, at those points, ‘is a ball point and not an ink well pen,’ comments Legato.” So the automaton did do the drawings, but not based on its complex system of gears and other clockwork visible inside it.]

How accurate is it?

Naturally the events of history are messier than the neat scenario of a mainstream film could encapsulate. Still, given the constraints involved, Hugo‘s modifications of the facts seem quite reasonable, and on the whole the general public will exit the theatre with a decent impression of Méliès’ career.

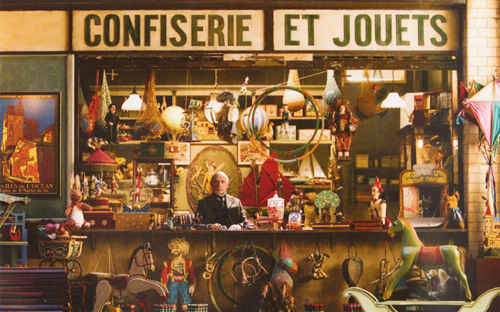

In fact he was married twice. Jehanne d’Alcy had been Méliès’ mistress well before they married in late 1925. They had both worked at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin before the cinema was invented, and d’Alcy appeared in many of Méliès’ films. (His first wife, Eugénie, died in 1913.) D’Alcy brought with her the ownership of a little candy-and-toy shop outside the Gare Montparnasse, which the couple transferred inside the station and ran together (see bottom). World War I did not cause the demise of Star Films. Méliès had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

As biographer Paul Hammond describes his decline, “Georges Méliès had become an anachronism, an artist left behind by economic and aesthetic developments.” In looking at Méliès’ late films, we might keep in mind that 1912 was the year of Albert Capellani’s remarkable serial adaptation of Les misérables. Max Linder was at the height of his popularity, and D. W. Griffith was making some of his finest one-reelers. The three great Swedish silent-era directors, Mauritz Stiller, Viktor Sjöström, and Georg af Klercker, all made their first films in 1912. The year 1913 would see a burst of cinematic inventiveness around the world, and Méliès would have seemed all the more old-fashioned by comparison had he continued to make movies. Nevertheless, he remains perhaps the only one of the very earliest generation of filmmakers whose work we return to not simply out of historical interest but for the fun and wonder of the films.

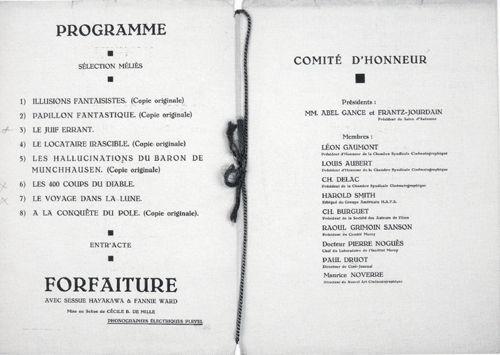

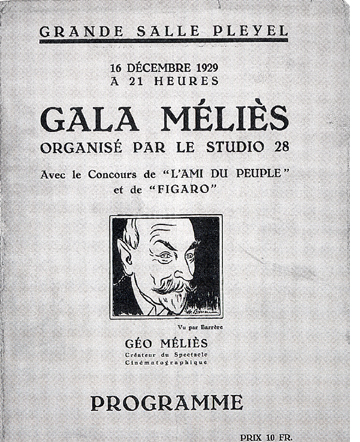

The rediscovery of Méliès began earlier than it does in Hugo, and it was more gradual. The mid-1920s were the nadir of his career. He and d’Alcy were living in a tiny flat in impoverished circumstances. In 1926, Méliès was notified that he had been made the first honorary member of the Chambre Syndicale Française de la Cinématographie–a trade organization, not an academic one like the fictitious “Film Academy” in Hugo. In 1929, J.-P. Mauclaire, director of the early art cinema Studio 28, found a batch of twelve tinted copies of Méliès films. New prints of the most damaged ones were made, and a screening of eight of them was held in a “Gala Méliès” that also included a revival of Cecil B. De Mille’s The Cheat:

In 1930 another program of Méliès films was shown, and in 1931 he received the Cross of the Legion of Honor. A benefactor provided Méliès and his wife with a larger apartment, and in 1934 he was made the honorary president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Prestidigitation. Ill health prevented him from pursuing some tentative filmmaking projects originated by admirers within the film industry, and he died of cancer in 1938. His granddaughter Madeleine ultimately became a champion in the revival of his memory. (For more on Méliès’ later life, see Paul Hammond’s Marvellous Méliès, pp. 80-85.)

Given all this, I think Scorsese and scriptwriter John Logan have done a reasonable job of condensing and tweaking the facts of Méliès’ story. The filmmakers also deserve considerable credit for showing the filmmaker cutting and splicing a strip of film involving a stop-motion effect. Méliès was long dismissed as not being much of an editor, having supposedly just stopped his camera and started it again to allow for the substitution of different items of mise-en-scene. We now know, however, that his amazingly well-matched transformations depended on eliminating just the right number of frames to create the magical illusion. He was a skillful editor indeed, and the filmmakers display that fact.

3D and Autochrome

Commentators naturally have stressed the fact that Scorsese has made his first 3D film. Up to now major filmmakers have embraced the technology, but most, like James Cameron, have worked in action genres. Could one of the “movie brat” generation redeem what has come to be seen as a technology that is rapidly losing its novelty value and perhaps its economic viability? The BBC even ran a story bluntly entitled “Can Martin Scorsese’s Hugo save 3D?” It and Steven Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin, have widely been seen as the crucial test of whether the use of 3D will continue to expand.

No doubt Hugo represents the best that can be done with current 3D technology. For once, every shot was filmed in 3D. Most 3D films, even Avatar, have at least a few images done with  post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

Cinematographer Robert Richardson has remarked on the idea of avoiding conversion: “If, as a film team, you’re not all working to best enhance in-camera the three dimensions then I would ask why have you committed to constructing a labour of love that someone else will eventually deliver to you via post conversion and say, ‘Here is your film.’ That might work for some projects and directors … but for me that choice felt insanely wrong. Commitment is required.”

Editor Thelma Schoonmaker has said of the 3D style “It’s not so much about stuff in your face—though there are a few wonderful shots like that. But more it’s about pulling the characters forward and feeling you’re in the room with them.” (Both quotations from Screen International [25 November 2011], p. 19.)

David and I went to see Hugo in 3D last week. Recently I have only seen a few 3D films: Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Wenders’ Pina, and Miike Takeshi’s Harakiri. Art-house films all, and apart from the Herzog film, where 3D serves educational rather than aesthetic functions, I didn’t think the 3D added much. James Cameron has said that Hugo is the best use of 3D he’s seen, and he should know.

I’ll admit that there are some terrific effects. The decision to have the Inspector’s doberman’s pointed muzzle coming out at us as it chases Hugo is clever and funny. But there’s still the blur and juddering of objects in the foreground, something that isn’t helped by the breakneck pace at which Scorsese “tracks the camera” through huge spaces or long tunnels. (Most of these shots involved as many special effects as actual camera movements.) I frequently wished in the course of the screening that I was seeing the film in 2D.

Apart from everything else, 3D pretty much necessitated that David and I move out of our habitual and preferred “front zone” of the theatre. Not only do 3D effects not work as well if you’re up close, but the edges of the screen are outside the frames of the glasses’ lenses. Turning your head when you’re sitting close and watching a 2D film is one thing; it’s quite another with those glasses on. So we sat further back. We also raised and lowered our glasses at intervals, checking out the amount of light being filtered out by those RealD glasses. It was quite a lot.

A few days later I went to see Hugo again, this time in 2D. The movie looked beautiful, with brighter images and more vivid colors. There was less blur in the fast camera movements. The depth cues in the images were strong enough to make such shots as the high-angle views down the vast clock tower impressive. And I was able to sit closer.

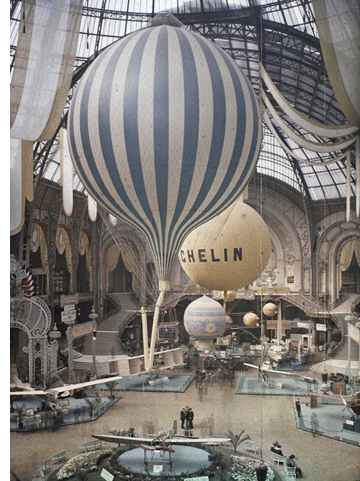

The brighter colors were important, since the filmmakers made an attempt to imitate a  photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

[Dec 9: A new interview with Robert Richardson by Bill Desowitz has just been posted here. It deals with 3D and Autochrome.]

Scorsese, journalists, and the legacy of Méliès

The reviews and coverage of Hugo in the trade and popular press have rightly emphasized Scorsese’s love of cinema history and his devotion to film preservation. He has collected high-quality 35mm prints of classic films, many of which are on deposit at the George Eastman House archive. Scorsese also helped found the Film Foundation in 1990 and the World Cinema Foundation in 2007. The latter organization has provided preservation work for films made in countries where either there is no national archive or where the archive lacks the funds and facilities for major restoration/preservation projects. Having first seen the Egyptian film The Night of Counting the Years (Al-mummia, 1969) in a battered 16mm copy, I was delighted to watch a beautifully restored 35mm widescreen copy at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in 2009. There is no doubt that Scorsese’s contribution to the film-restoration effort has been immense.

That said, I think some of the press coverage of Hugo has pushed Scorsese’s interest in preservation a bit too far in the case of Méliès, giving the impression that somehow the director has led a rediscovery of the early film pioneer as thorough as the one accomplished by Hugo and his friends in the fictional account. In The Hollywood Reporter’s story, “The Dreams of Martin Scorsese,” Jay A. Fernandez writes, “Over the years, Méliès has become a mystery himself, and even film buffs often don’t have a grasp of just how profound his contributions to cinema were, despite their efforts to piece together the scraps of his legacy. In this, he could not have better cultural archaeologists than Selznick and Scorsese.”

One might overlook a journalist (albeit one who specializes in entertainment news) believing that Méliès really was virtually forgotten among all but a few film historians before Hugo came along. But he goes on to quote Selznick, whose words might carry more weight, as saying of Scorsese, “Of course, Scorsese has been responsible for restoring the lost legacies of groundbreaking filmmakers. He is in the position of pointing the way for the public, showing us who has been forgotten and overlooked.”

That’s going a bit far. Admirable and important though Scorsese’s preservation efforts have been, and valuable as his video histories of topics like Italian cinema have been in bringing film history to a broader public, he cannot be said to have been responsible for rediscovering major filmmakers who have been forgotten. I doubt he would claim to have done so.

The work of Méliès has been covered in the basic histories of world cinema for at least the past fifty or sixty years. Indeed, the rediscovery of Méliès that began in the 1920s has continued ever since. Unfortunately, most of the coverage of Hugo passes over the diligent and successful work of archivists who have been the mainstay of that rediscovery.

The friends of Méliès

Méliès played a small but important role in my own early discovery of cinema history. During the spring of 1970, I was taking my first film course, a one-semester survey history, at the University of Iowa. As I recall, it was during that time that a representative of the Library of Congress came to campus and gave a talk on film preservation. He showed two hand-painted shorts, one of which was Méliès ’ Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en deux heures. The color was crude, to say the least. In 1905, without the benefit of a stencil, someone had daubed a dot of red paint onto the race-car in each frame, leaving the rest of the image in black and white. The result looked like a flickering, burning car was driving through magical landscapes. I found it quite fascinating, and that, along with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, were the films that really lured me into film studies and a career. I regret that the prints of Le Raid used for the DVD releases of Méliès ’ work have not included this clumsy but charming hand-coloring.

During my years in graduate school, the general claim was that something like a hundred of Méliès ’ output of around 500 shorts survived. By now, the number is more like slightly over two hundred. Occasional discoveries continue to be made.

In 2008, when Flicker Alley put out its monumental five-disc set, “Georges Méliès : First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913),” it contained 173 films—not quite all of those that were known at the time to survive. In 2010, the same company released “Georges Méliès : Encore” appeared, a single disc with 26 newly discovered prints. (I note that both are temporarily out of stock at Amazon, suggesting that Hugo has generated new interest in Méliès.) For our comments on the “Encore” disc, see here.

This flow of rediscoveries has been due to archivists like Paolo Cherchi Usai at Eastman House and Serge Bromberg at Lobster Films (two of the many archives contributing to the set released by Flicker Alley in the U.S.). David and I played a modest role in one such discovery. We spotted an ad in a film-collectors’ publication, offering for sale a nitrate original of a hand-colored Méliès film. We alerted our friend Paolo, who obtained the film; it turned out to be a lost Méliès title from 1899, in excellent condition.

Lobster Films appears in Hugo’s credits as the supplier of many of its clips from Méliès films. I wish more journalists would have made mention of Lobster. So far the only reference I have found is in Susan King’s story for the Los Angeles Times, “‛Hugo’ revives interest in Georges Méliès.” She includes a brief overview of Lobster, as well as a list of Serge’s suggestions of six Méliès films “that are must-sees.” (For our coverage of an encounter with Serge in Paris last year, including a 3D projection of part of a Méliès film, see here.) This article also contains the happy news that next year will see the release of a DVD containing the recently restored hand-colored version of A Trip to the Moon (bits of which are glimpsed in Hugo) and a documentary concerning the restoration, The Extraordinary Voyage.

Méliès has also been known to the public, at least in France and the U.S., though some lavish exhibitions and publications. Fortunately many of his designs and drawings have survived. Copies of them are tucked away in the armoire in Hugo. There are also numerous photographs and objects from the era. A 1991 exhibition at George Eastman House, “A Trip to the Movies: Georges Méliès Filmmaker and Magician (1861-1938),” was accompanied by an anthology of essays of the same name. In 2002, the Parisian show “Méliès, magie et cinema” resulted in a coffee-table book of the same title. In 2003, the Cinémathèque français held another exhibition, “Georges Méliès, magicien du cinéma”; it occasioned the publication of a large volume, L’oeuvre de Georges Méliès, which catalogued the archive’s holdings in gorgeous reproductions.

Historical reference books have not been lacking. In 1975, Paul Hammond published his Marvellous Méliès, a thorough and still useful book. It was followed by John Frazer’s excellent Artifically Arranged Scenes: The Films of George Méliès. There are other books on Méliès, too numerous to list in full here.

Since 1961, “Les amis de Georges Méliès,” a group founded by the filmmakers’ descendents (who are acknowledged in Hugo’s credits), have fostered the rediscovery and preservation of his legacy.

Now, go and watch Le Déshabillage impossible (1900, disc 1 of the Flicker Alley set), a two-minute film that remains as astonishing as it is hilarious. If you’re not a friend of Méliès now, you will be after seeing it.

[Dec 7: Thanks to Mark McElhatten for pointing out the mistake concerning the character Tabard in Zero for Conduct, a mistake which has apparently appeared in some reviews of Hugo.]

[Dec 8: Thanks to Paolo Polesello for reminding me that the rediscovery of Méliès included Georges Franju’s short film, Le Grand Méliès, 1952; it’s included in the five-disc Flicker Alley set.]

[Dec. 12: Today Variety posted a story about modern designers and special-effects experts who have been inspired by Méliès, in particular those who have eschewed CGI and opted for prosthetics, animatronics, and miniatures.]

Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex

Advertisement for NEC digital projectors, Variety July 2005.

ELECTRONIC CINEMA IN THE WINGS

Not only will [HDTV] usher in a new era of dramatically enhanced sharper-picture, improved color, wide-screen, stereophonic home TV, but HDTV will give rise to what’s already being called “electronic cinema”—high-definition video used to make 35mm quality theatrical feature films.–Variety, January 1982

FAROUDJA TOUTS VIDEO FOR BIGSCREEN

Faroudja and Videac seek to demonstrate that today’s technology makes it quite possible to display video images in a theatrical environment of a quality that can stand comparison with 35mm film. —Variety, June 1989

DIGITAL TECH POINTS TO PIX’ FUTURE

In the midst of a digital revolution that is embracing television, cable, and telephones, the movies certainly aren’t immune. Appearing soon in a theater near you will likely not be film at all but a digital projection that looks like the real thing. —Variety, May 1992

DIGITAL CINEMA HOVERS ON HI-TECH HORIZON

“I really do think at least a couple of the major players are pretty close.”–Variety, June 1995

WHEN PRINTS WILL NO LONGER BE KING

While the eventual replacement of 35mm projectors by video systems was seen as an inevitability—and a welcome one, at that—most agreed it was still far in the future. But after seeing six state-of-the-art systems beam images onto a 40-foot-long screen at the United Artists Denver Pavilions complex, many attendees agreed that the future is already upon us. — Variety, January 1999

Aug. 15, 2004: Using his computer keyboard and mouse, the president of top U.S. theater chain Regal/ Loews-AMC books the upcoming weekend’s films into his circuit’s theaters.

As he clicks on the titles (“Austin Powers 4: You Only Shag Twice,” “The Matrix III,” and MGM’s long-awaited “Supernova”) the films begin downloading via satellite to the circuit’s digital megaplexes around the globe. —Variety, August 1999

DIGITAL CINEMA’S PICTURE STARTS TO FADE

A few years ago, cinema operators were open-minded, but not any more. Now it’s clear that the first-generation digital projectors—brand-spanking-new equipment installed in 116 screens worldwide, out of an estimated 108,000 cinema screens globally—is rapidly becoming obsolete. — Variety Deal Memo, July 2002

AT LONG LAST, DIGITAL THEATERS

Finally. Digital cinema is here. No, really. . . . The conversion of of 35,000 US screens to digital projection can begin in earnest.

. . . . All six “Star Wars” films will be converted for 3-D re-release, perhaps as soon as 2007. —Variety, July 2005

DB here:

Reading things like this over the last couple of decades, I smiled patronizingly. The shift to digital, hyped from the start, sounded both inevitable and impossible. Even the ad for NEC at the top didn’t faze me. I’ve seen braggadocio before.

In my smugness I forgot that most broad changes take a long time to be consummated. Historian Jim Cortada writes that a new technology may wait as long as forty years before an industry decides to adopt it. I should have remembered that in cinema many hardware changes, such as color movies, took a surprisingly long time to become dominant.

Now everybody has woken up. We realize that we’ve crossed a threshold. Henceforth digital projection will be the norm.

Some numbers back up the impression. In December 2000 the world had 30 commercial digital cinema screens. In 2005 it had 848. At the end of 2010 it had 36,103—about thirty per cent of the total 123,067 screens. In North America, the jump was dramatic, from about 330 d-screens at the end of 2005 to over 16,000 at the end of 2010.

This year has iced the cake. In the UK, 80 % of releases were digital. At Cannes there were a great many digital screenings, even of films shot in 35mm. In Belgium the two major theatre chains, Kinepolis and UGC, went wholly digital. In Norway all 420 commercial screens were converted, partly because the government funded the changeover. Closer to home, the dominant chain in our region, Marcus Cinemas, went digital and fired its projectionists—ironically, just before Labor Day. My local theatres are junking their 35mm equipment. Roger Ebert recently posted a letter from Twentieth Century Fox announcing that “within a year or two” it won’t be sending out film prints.

Given all this, the newest predictions don’t look as Pollyannaish as the ones I listed up top. “Some time in 2013,” says a spokesman for the National Association of Theatre Owners, “all the [U. S.] screens will be digital.” Next year, half the screens in the world are likely to be. By 2015, predicts IHS Screen Digest, film-based projection will be defunct in commercial cinemas.

I’m not smirking now. Digital cinema is here.

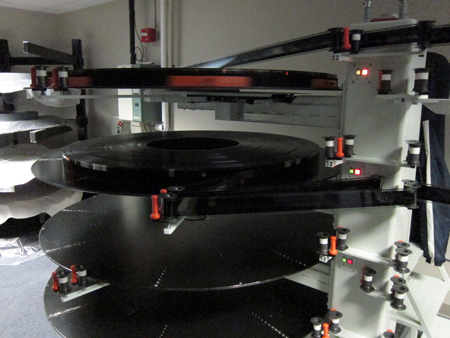

The booth

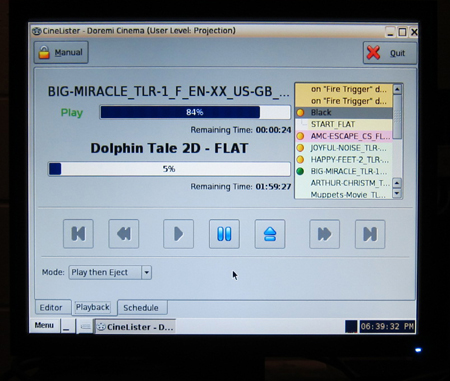

“Here,” of course, is a place still in transition. I saw that back in September when I paid a visit to my local, an AMC multiplex in Fitchburg, Wisconsin. Its projection booth, a vast tunnel running almost the breadth of the building, reflected the changes in progress. Several 35mm projectors were still humming away, pulling the film from one big platter to another. There were some digital projectors too, one being the Sony SRX-R320.

You’ll notice the two lens housings on the right, suited to 3-D. Using these lenses for screening 2D films is a bone of contention in the current controversy about digital projection. (See the codicil for this entry.)

There was one Christie digital projector, run both from a computer and a touch-screen.

The heart of the system is the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), shown above. It’s a cute item, a little taller and skinnier than a trade paperback. It comes in a bright red carrying case padded with pink foam. Essentially, it’s a hard drive containing files for the image, sound, and subtitles, as well as files for playback, security, and encryption. The film is compressed; an hour-long movie at the maximum rate would take up about 115GB on a DCP. Trailers and specialized content, like Met Opera shows, come on their own DCPs.

The DCP files have to be opened, with password keys supplied by the distributor. The files are then loaded into either a projector or a server in the booth. Loading can take several hours. A projector like the Sony can hold half a dozen or more features. Since the projectors are essentially big computers, the features, trailers, ads, and the like have to be arranged in a playlist, accessed by either a touchscreen, a laptop, or both.

The fear of piracy has kept back one early aim of the digital cinema revolution: Delivery of content via satellite or the Net. These are apparently too vulnerable to hacking or crashing. So the DCP is delivered the old-fashioned way, by courier services like UPS and FedEx. The decryption keys are sent by email or by a much older technology: the telephone. Often exhibitors and projectionists—sorry, Mr. or Ms. Screen Management System—has to phone somebody to learn the codes to tap in.

Turning points before the tipping point

The digital switchover seems sudden, but like most historical change there’s a story to tell about it. The digital changeover in movie houses was delayed by many factors, but the problems were solved, as usually happens when there’s money to be made and people are in the grip of the next big thing.

Here are four factors that, to my mind now, made the difference. They didn’t crop up in neat sequence, but they developed in an intertwined fashion before gathering in a knot in the last year or two.

1. The setting of standards

Standards are of immense value to the film industry. It’s to everybody’s interest to have movies run at the same rate, but if you think you can improve on 24 frames per second (sometimes 25 in Europe), you will have a long climb. (Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill have found this in arguing for higher frame rates.) Technological change in Hollywood consists chiefly of the Majors cooperating with each other to mutual benefit, while setting up barriers to entry that exclude outsiders.

For the most part, standards in film have been set not by trade associations or government agencies but by the major players: the technology suppliers and the studios. Innovations in sound, picture, color, and widescreen tended not to come from within the filmmaking companies but from outside firms and lone inventors, eventually to be accepted by the majors. Only then do the trade associations and other institutions get into the act.

The standards are often in flux, constantly adjusted to practical concerns. What, for instance, is the CinemaScope aspect ratio? Designed originally to be 2.66:1, twice as wide as the 1.33 format, it went to 2.55 and then to 2.35, partly because of Twentieth Century-Fox’s responses to the market. Later that standard was modified again, to 2.40. The Society of Motion Picture Engineers, which has historically tried to stabilize the technical standards, often played catch-up, refining or revising standards that were already common practice on the ground.

The real momentum for standardization comes when the American film studios, as an oligopoly, decide to throw their weight behind an innovation. This is what happened with the DVD and the Blu-ray disc (and may happen with higher frame rates for digital). Once the decision-makers have surveyed the range of options out there, usually offered by very big technology companies, there ensues a process of negotiation, testing, and horse-trading before a standard is arrived at. And even then the standards might be pretty flexible.

For digital projection, the oligopoly’s concerted effort began in 2002, when the six major studios formed a joint venture, the Digital Cinema Initiatives, LLC. As the studios in the 1920s had recruited the American Society of Cinematographers to test incandescent lighting systems, so they now had the ASC create material for testing digital projectors. The DCI also hired universities and private agencies to test the systems. Some interim documents proposed requirements, and the full set of specifications was issued in July 2005. This 161-page document has been revised, but it remains the bedrock for any manufacturer, theatre chain, or projectionist (defined in the text as part of the “Screen Management System. . . the human interface for the Digital Cinema System”).

![]() The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

Secure Processing Block behavior and suite implementations shall permit the SM to prevent or terminate playback upon the occurrence of a suite SPB substitution or addition since the previous suite authentication and/or ITM status query. The SMs shall respond to such a change by immediately purging all content and link encryption keys, terminating and re-establishing: a) TLS sessions (and reauthenticating the suite), and b) suite playability conditions (KDM prerequisites, SPB queries and key loads). “Prepsuite” command(s) shall be issued per (9) prior to the next playback.

This is a far cry from what projectionists and theatre managers have traditionally known how to do. The opacity of the DCI specs may have the effect of disempowering traditional film workers and shifting their responsibility to the maintenance manager working for the manufacturer or some other third party. In any case, as had happened with sound and widescreen systems, the American film companies set the standards for the world.

The publication of the DCI report led to the exuberance in my last quotation at the start. With this in place, surely digital cinema had arrived in 2005 (along with the imminent release of all six installments of Star Wars in 3D). Yet a report last March found that most projectors currently in use weren’t fully DCI compliant; Sony and other companies came up with fully compliant equipment only this year. So thousands of projection systems were in operation outside the DCI standard, working under the rubric of “interoperability.” As usual in the film industry, practical demands outpaced standardization. 2011’s new lines of projectors from major providers are DCI compliant, which should attract exhibitors who were hanging back to see how all this got sorted out.

2. Convergence of hardware

A key condition laid down by the DCI was a requirement that digital exhibition be 2K or 4K resolution. That eliminated some systems outright, notably the unsatisfactory 1.3K format that had had some take-up in the US and had proliferated in foreign markets such as India (and are still flourishing there under the name of “e-cinema”). 1.3K systems were in the majority until 2005.

For 2K or 4K projection, Texas Instruments had already developed its Digital Light Processing system, consisting of thousands of microscopic mirrors, and this was adopted by three major manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. Sony developed its own system using modified LCD technology, claiming that only that can do justice to 4K projection. These four companies dominate the digital theatre market. All were producing machines in numerous models by the end of the 2000s.

China and Russia, both growing markets, proved particularly important, as their newly built theatres skipped 35mm altogether. The expanding markets gave the companies vast quantities of business; Christie reported that over 600 sites in Asia installed its projectors in 2009, while Barco claimed that it had 80 % of all installed screens in China. In Russia, of the 297 new screens added in 2010, 256 were digital. This surge from the periphery gave impetus to the US changeover as well, as brisk sales permitted the manufacturers to refine their systems and hatch new models.

3. The Virtual Print Fee

Historically, exhibition has been the most conservative wing of the film business. The theatre owner has the most to lose if a new technology fails to catch on. It was theatre chains’ reluctance to install magnetic-stereo sound systems that led Twentieth Century-Fox to redefine CinemaScope to 2.35, lopping off some picture area to make room for an optical soundtrack that would play on existing projectors.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

The big three theatre chains in the US—AMC, Regal Entertainment, and Cinemark—control about 20,000 of the country’s 39,500 screens, and they were reluctant to embrace a technology that could cost them a couple of billion or more. If these dominant exhibitors wouldn’t jump in, no smaller circuits would convert. Moreover, the studios preferred a quick conversion. Distributing both 35mm and digital versions was costlier than either one alone.

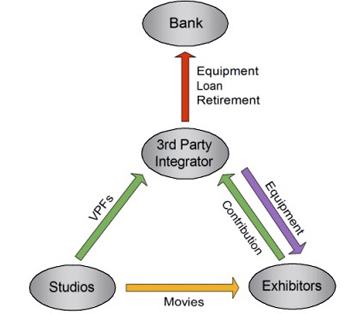

The solution was the Virtual Print Fee. Five studios agreed to help the big three finance the cost of conversion, to the tune of $1 billion. The VPF is a subsidy paid by the distributor. Under one common arrangement, it’s collected by an intermediary, known as a third-party integrator; the dominant integrators in the US have been DCIP and Cinedigm. The integrator loans the digital equipment to the theatre. For each booking the exhibitor makes, the film’s distributor gives a sum to the integrator (negotiable, but said in 2005 to be $1000 or so). But the VFP doesn’t cover the entire cost; the exhibitor has to chip in. Eventually the equipment is paid off and belongs to the exhibitor. (The accompanying diagram is taken from the informative site hosted by MKPE Consulting LLC.)

To speed up wide installation, most VPFs were set to expire at the end of 2012, although some are likely to be renewed or extended. Recently, Christie’s has initiated a VPF program aimed at independent exhibitors. Europe and Asia have VPFs and integrator go-betweens as well.

Most observers credit the VPF policy as a principal cause of speedier digital conversion, but there was another factor at work.

4. The killer app, 3D

The studios’ concerted offer of a Virtual Print Fee occurred in October of 2008, just as the world economy was heading down the drain. Credit was tight, and the rate of digital conversion was slowing. 3D came along at the right moment. Exhibitors learned that there was a line-up of big 3D films for 2009, all from the studios offering the VPF. A theatre that wasn’t set up for digital couldn’t play these titles.

Chicken Little (2005) showed the way, and in the following years a few films gave other promising results (Monster House, 2006; Meet the Robinsons, 2007). Concert films, especially Hannah Montana (2008), helped too. But Monsters vs. Aliens (2009), which played Imax houses as well as normal 3D ones, was a turning point: it grossed nearly $60 million in the US over its first weekend, more than half coming from 3D screens. The studios stepped up their production of 3D titles, from five in 2008 to eleven for 2009 and over twenty in 2010. Exhibitors saw that they could charge between $2 and $5 more for a 3D ticket, and this boost could help defray the costs of converting to digital presentation. Avatar seemed to seal the deal; it became the top-grossing film of all time (in absolute, not relative dollars), and after 47 days, over 80% of its $2.075 billion gross had come from 3D screenings.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

I haven’t touched on other forces working in favor of digital theatres. Exhibitors were surely happy to embrace an automated system that would allow them to dismiss expensive unionized workers. Digital projection also opened up the possibility of using a venue for “alternative content”–pop concerts, opera broadcasts, sports events, and business meetings with snazzy presentations. Distributors gained as well. Besides saving money on prints and shipping—the public rationale for the switch—distributors could now monitor the number of screenings at any venue. A DCP-wrapped feature is set for only a certain number of runs. To extend the number of screenings, the exhibitor needs a new key code. This prevents off-hours screenings, a common practice of old-school projectionists. In addition, distributors suspected projectionists of video-recording prints or bicycling them for overnight telecine copying. (After Web 2.0, however, prime sources of bootleg copies have been workers in the industry itself.)

The past regained

Historians shouldn’t predict. I succumb sometimes, but I always regret it later.

Even professional predictors shouldn’t predict, as we see from a 2002 Credit Suisse First Boston report on digital cinema. That document declared that Eastman Kodak was the technological “winner” and would benefit from its “sensible business plan.” The report added that Kodak’s film business should face “minimal deterioration” from digital cinema. They valued Kodak’s Entertainment Imaging branch at $2 billion. Today Kodak’s entire company is valued at $900 million and its stock trades at $1.10 per share, down from the $30s in 2002.

So, no predictions from me. But warnings and worries? Yes, quite a few. Next time I’ll share some concerns about festivals, repertory cinemas, arthouses, colleges and community centers who depend on 35mm prints—especially older titles, our link to the history of the medium. Eventually we’ll get to archives, the repository of said history. I hope as well to offer some general thoughts about the redefinition of “film” in the high-def era.

In the meantime, let’s remember what was.

Alongside the 35mm and digital houses at the AMC Star Fitchburg 18 stands a very good Imax facility. If the digital gear shows us the present and future, I had the feeling that the monstrous Imax 3D projector, devouring two huge reels of 70mm film at the same time, was the world’s last movie machine.

Two fat ribbons, destined to intersect for an instant, whir past you, zigzagging around rollers, turning the room into a web of film. A pair of images snap into the gate. Each is sprayed with a puff of air. You must keep the film and lens clean; even a speck of dust looks like Rodan on the Imax screen.

Holding 35mm film in your hand is a pleasure, but 70mm is almost menacing. Even with 35mm, you need a loupe to see detail, but 70mm just boldly shows you everything, bright and crystalline.

The intimidating image suits the hardware that runs it. In the Imax 3D film projector, you see that mixture of enormity and delicacy, thrusting energy and exquisite precision, that characterized mass printing, tool-and-dye, and the rest of good old US industry since the nineteenth century. The whole contraption looks like a giant doing needlepoint. Yes, the sound system is digital, but you couldn’t find a more stubbornly old-fashioned way to display pictures—themselves big, palpable, and gorgeous. It puts you in mind of sledgehammers and nuts: All this just to show a movie? By all means.

This is the first of a series of entries reflecting on digital cinema.

Statistical and trend-based information in this entry came from back numbers of Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and above all IHS Screen Digest, the premiere source for media industry data and analysis. Most of the articles and reports I consulted are proprietary or available online only by subscription.

On the web, the site I mentioned above, run by the consulting firm MKPE, is an excellent general source on digital exhibition. For a superb introduction to the Digital Cinema Package, see this article by Arne Nowak. Box Office Mojo offers a useful chart of 3D releases. Go here for a Roger Ebert’s entertaining interview with Katzenberg, who even comments on cutting rates in 3D. Grady Hendrix offers a lyrical portrait of the endangered species of projectionist.

The controversy around Sony’s 3D lenses arose when 2D films were projected through them, leading to a loss of light on the screen. The primary article on the matter is Ty Burr’s piece. Jim Slater explains the task of swapping lenses in “The World of Sony 4K,” Cinema Technology Magazine (September 2010), p. 30. You can decide for yourself how difficult it is to change the lenses by watching this video.

For a historical account of how the studios and their affiliated organizations, like the Academy and the American Society of Cinematographers, have coordinated technological innovation with manufacturers and supply firms, see Parts Four and Six of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, by Janet Staiger, Kristin Thompson, and me.

Jim Cortada provides an overview of how computers revolutionized several media industries in his indispensable The Digital Hand, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2006).

Thanks to Rick Reavey and Adam Hasz of AMC Star Fitchburg 18.

PS 3 December 2011: As is well-known, Peter Jackson is shooting The Hobbit at 48 frames per second and James Cameron is planning to shoot either 48 or 60 fps on Avatar II. They believe that the higher frame rate will improve the quality of 3D images. A recent article in the print edition of Screen International (I don’t find it online) indicates that DCI standards don’t specify 48 fps for 3D, and that currently available projectors don’t permit it. The projectors can be adapted for it, but it probably means 2K rather than 4K resolution in the screening. See Adrian Pennington, “Life in the Fast Frame,” Screen International (25 November), 8.

PPS 3 December 2011: Here’s an item on Creative Cow by Doug Trumbull that addresses some issues in digital projection and discusses, yes, frame rates. Thanks to Stew Fyfe for the tip.

On your left, the past: A person and a film. On your right, the future: A black box.