The Skin I Live In.

DB here:

Contemporary Hollywood films can play prettily with time, parallels, and point-of-view, at least within certain boundaries. (We’ve talked about this with Source Code [2], Inception here [3] and here [4], and other titles [5] further back.) But if you want to see filmmakers coloring outside the lines, a film festival provides a wider sampling of ingenious storytelling strategies.

Last year, in “Seduced by structure,” I wrote about films that worked ingratiatingly with flashbacks, stories within stories, and the like. I’m still a sucker for these things, and several of the offerings at the Vancouver International Film Festival [6] have enticed me. Since these are rather new films, I’ll try to avoid spoilers.

Flashbackhand

Harakiri.

Perhaps the simplest case I’ve encountered so far is Miike Takeshi’s 3-D Harakiri: Death of a Samurai. It’s seventeenth-century Japan, and penniless samurai are eking out survival through the “suicide bluff.” They arrive at a noble house and ask to commit seppuku on the premises. Because the family won’t risky sullying the family name, the ronin are paid to go away. But the head retainer of the house of Ii is done with the game. The suicide bluff, he maintains, dishonors the samurai code.

A severe-looking ronin appears and asks to die in the Ii compound. The retainer explains to him that recently they had a similar request.

Thus begins the first of two flashbacks. It’s confined to the visit of a very young samurai making the suicide petition, with harsh and grisly results. We return to the narrating frame, and we find that the original petitioner isn’t dissuaded. Why not? And why are the three swordsmen most implicated in the young man’s visit missing today?

A second flashback, more or less from the standpoint of the older petitioner, goes far back in time to fill in the youth’s identity and background. This structural choice shows several worthy things that a flashback can do. It can flesh out things that were merely hinted at earlier, in both the present-time sequences and the first flashback. The flashback can create mysteries by virtue of its placement, as indicated earlier. It can build its own narrative momentum: Even though we know vaguely how things are likely to go, we get to see the gaps filled in with unexpected details.

The flashback pattern also creates two layers of response. We know the young man’s fate, so everything in the leadup gains an extra pathos. Meanwhile, as we recall the present-time situation, the older petitioner’s action remains suspended and we want to return to it to see how it develops. A bonus is that arranging the film in flashbacks allows an intense, arresting scene to appear at the film’s beginning, with the young ronin’s petition, and then assign a cluster of swordplay fights at the end. Arranged in linear story order, the scenes would have created a slow-burning opening and a crowded conclusion, with several violent scenes close together.

A more audacious play with flashbacks is found in Pedro Amodóvar’s elegant, decadent The Skin I Live In. As with Harakiri, we begin far along the story’s development. A beautiful young woman is imprisoned in a postmodern equivalent of the mad scientist’s lair, a designer house filled with sumptuous furniture and high-tech gadgetry, including a close-circuit video system that lets the doctor keep an eye on his prey. Already there are plenty of questions, particularly when the young woman, Vera, asks to stay with Robert forever.

We quickly asume that she is the object of the doctor’s experiment in creating unblemished, fire-resistant, and snugly fitted human skin. (Almodóvar used a digital intermediate chiefly for the purpose of making the actress’s skin perfect) But more questions arise when a horrendous jewel robber named Zeca, dressed in a tiger skin (it’s the carnival season), breaks into Vera’s sanctuary.

Melodramatic twists come thick and fast, and the first flashback, sponsored by the maid Marilia, tells us of how Robert’s first wife was burned in a car crash. His daughter Norma saw her mother commit suicide and became deeply disturbed thereafter.

The family history gets even more tangled with two later flashbacks. One, initiated by Robert as he sleeps (though it seems more “objective” than a dream) takes us back six years and fills in more of Norma’s sad history. The second, more peculiar, return to the past is obliquely introduced by Vera. The narration seems pretty reliable, and it replays some of the events presented in Robert’s flashback. The curious thing is Vera doesn’t appear in any of the scenes. Shouldn’t she be present for at least some of the action she is “recalling”?

The question is answered with the sort of shocking finesse that Almodovar summons up effortlessly. The flashbacks in Harakiri fill in and flesh out what we’ve seen, while the flashbacks in The Skin I Live In reveal layers of shocking discoveries about what’s really going on in the present-time situation. The flashback structure doesn’t fulfill the film’s opening so much as yank the bottom out from it. Perverted story action summons up perverse narration.

I wish I could say more about these formal arabesques, but secrets must be respected. Suffice it say that Miike provides us a sober, dignified jidai-geki making modest use of 3D and lacking the outlandish gore that he’s come to be identified with. It’s not even as action-oriented as last year’s 13 Assassins. Harakiri ‘s most striking moments are quiet ones. A woman picks splinters out of her dead husband’s bloody hand. Earlier the same poverty-stricken man, having dropped a pair of eggs on the pavement, stoops and licks up their contents.

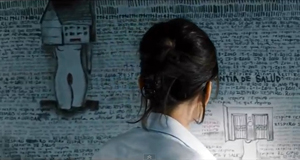

As for The Skin I Live in: Almodovar’s eye for fashion is still teasing; the credits list is a pageant of brand names like Gucci and Prada. He can also plant nifty little motifs, as when the tidy graffiti with which Vera has filled her cell are echoed by the window display in a dress shop.

As usual, the story of revenge and unspeakable desire, or rather revenge as unspeakable desire, is wrapped in smooth technique, wondrous music, and eye-gratifying palettes. The flashbacks help too.

She said, he said

Split plot structures have become more common in recent years. Hong Sang-soo provided one of the most striking versions in The Power of Kangwon Province (1998); a recent instance is Apichatpang Weerasethakul’s Syndromes and a Century (2006). In the most common case, the film is split into two long sections, with each line of action following a different character or presenting alternative possibilities. Sometimes the lines present successive lines of action, as in Chungking Express. Sometimes the lines are more or less simultaneous, suggesting different viewpoints on the same events. Often the two lines intersect, so we get scenes replayed from different viewpoints or suggesting alternative versions of events–even parallel universes.

This sort of cleft plot patterning is exploited engagingly in The Natural Phenomenon of Madness, a Filipino film by Charliebebs Gohetia. A brief prologue sets up the situation. A man and a woman, friends since childhood, are having sex, and suddenly it turns rough. Both will later think of his action as a rape. He leaves in the morning, she chops off most of her hair, and they proceed to live their lives separately, sometimes converging, usually not.

The first long chapter, called She, follows her days wandering the city, signing up for a medical study, visiting a grave, inducing a miscarriage, and pursuing Him, whom she loves more than anyone. The second section, “He,” traces his efforts to induce another woman to marry him, to assuage his guilt about the rape, and to get Her to help him with his bone-marrow transplant. Both lines are taking place at roughly the same time and pace. The woman’s autobiographical monologues addressed to offscreen medical personnel are paralleled by the man’s increasingly sorrowful confessions to a priest. She’s a Bohemian artist, He’s a store owner wracked by Catholic guilt. At times, we see them doing things alone that suggest a sort of spiritual synchronization: She stands at a bridge and shouts, and later we see Him doing the same thing.

He and She meet occasionally, and then we get the same scene twice. Or do we? Every repetition is played out in symmetrically varied ways. For instance, early in the She chapter, He is already seated by a wall playing with an origami (of the sort my grade school used to call a Cootie Catcher). She joins him.

In His story’s version, she’s already there, playing with the origami, and He comes to join her.

Moreover, the conversation isn’t the same each time. So are the apparently iterated scenes completely different meetings, taking place in the same locale and filmed in similar fashion? Some cues suggest that the tandem sequences represent only one occasion. For instance, both of these wall scenes purportedly show their first meeting since She cut her hair. As we’re watching, we might be forgiven if we’re not sure of the variations: The repetition comes about 67 minutes later than the original scene. We’re left with meetings that are partly repetitions, partly variations: alternative universes embedded in one, perhaps.

One effect of the parallel plotting is to heighten the differences between the two protagonists. As Gohetia suggested in the Q & A after the VIFF screening, She actively chooses ways of living her life, while He clings passively to his situation, hoping that the other woman will marry him, that somebody will donate bone marrow, and that the Church may offer help. Both have unrequited love: She wants him, He wants another girl. There are plenty of abstract parallels, such as that between the medical establishment and the clerisy, but the precise, locked-down shots help us notice physical differences too, such as the walk through Manila streets with distinct gaits. And the final convergence of the couple nicely echoes the prologue. The Natural Phenomenon of Madness shows that once a new narrative strategy enters the public domain, filmmakers can play with its components, twisting them like facets of a Rubik’s cube to engage us in fresh ways.

The Skin I Live In will be released in the US by Sony Pictures Classics [12] on 14 October. The American Cinematographer story on the making of the film may be read here [13].

P.S. 6 October 2011: Thanks to Philippe Mathieu for correcting an erroneous film title!

P. S. 14 August 2012: Thanks to Marvin Ortiz for correcting two characters’ names in my account of The Skin I Live In.

The Natural Phenomenon of Madness.