Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

DB here:

Last week, Raúl Ruiz died [2]. His death is an enormous loss to world film culture, not least because his penultimate work, Mysteries of Lisbon, brought him a prominence he had been denied throughout his forty-year career. More important, we lost a modest, kindly, and zestful man.

From the mid-1960s through 1975, it seems to me, there emerged an interesting in-between group of filmmakers. By then film festivals had canonized an official art cinema typified by Fellini, Bergman, Wajda, and the New Wave. Now there appeared a more capricious clutch of directors, of varying ages, who pushed in a more avant-garde direction. Many made outstanding short films, like Wenders’ Same Player Shoots Again, or the Straub/ Huillet Not Reconciled, or Akerman’s Hotel Monterey, or the peculiar early efforts of Peter Greenaway.

When they turned to features, this group of directors produced films like October à Madrid (Marcel Hanoun), The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (Straub/ Huillet), Fata Morgana (Herzog), Katzelmacher (Fassbinder), and Jeanne Dielmann (Chantal Akerman)—more rigorous and forbidding than anything attempted by the older generation. In later years some of these talents moved comfortably into the festival niches vacated by senior directors, but for many years most were little known outside a small circle.

If they were marginal to most moviegoers, Ruiz was marginal to them. Exiled from Chile, where he made his first features in his twenties, he moved to France in 1973. There he proceeded to direct over a hundred films, often financed by television, while staging plays and running the Maison de la Culture in Le Havre.

His films’ repute was in inverse proportion to their availability. He was celebrated by critics in France (Cahiers du cinéma took up his cause) and England (particularly by London’s Afterimage group). Ruiz had his fans in North America too, notably Jim Hoberman and David Ehrenstein. But the films were chiefly seen at festivals, and none of his productions of this period, so far as I can tell, found stable distribution, theatrical or nontheatrical, in the United States. In 1989-1990, while Ruiz was teaching at Harvard, a batch of his films was circulated here by the quixotic International Film Circuit.

What set him apart from the other marginals was a devotion to esoterica (philosophical, literary, ecclesiastical), pursued with a sly humor. He remarked that during one screening, he was the only person laughing at his movie. Although like most of his contemporaries his sympathies lay on the left, he didn’t seem to take himself seriously, and this put him at a disadvantage in 1970s-1980s world film culture. True, Herzog had a comic side, and in The Falls Greenaway offered whimsy, though of a relentless, almost oppressive variety. Most other directors, though, were somber as well as severe. But Ruiz enjoyed intellectual lampoon, pastiche, clever cross-references, and straight-faced absurdity; the Chris Marker of Letter from Siberia (1957) is perhaps a predecessor, though Marker himself didn’t escape Ruizian parody.

Ruses

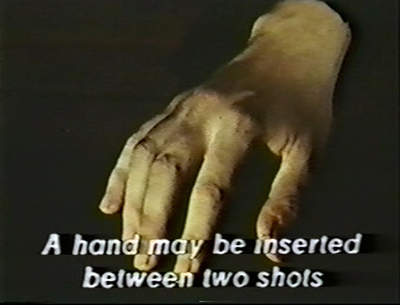

Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

Having seen about ten percent of the Ruiz oeuvre, and a lot of it quite long ago, I can’t offer a comprehensive appraisal. (Visit the bottom of the page for some more assured threads through the maze.) For reasons that will be understandable to regular readers of this page, however, I feel obliged to write something in his memory. I merely offer some observations on aspects of his work.

Ruiz often based a film on a striking formal premise, what Henry James might call a donnée. Socialist Realism (Considered as One of the Fine Arts) (1973) began, Ruiz tells us, from the idea of

having two stories that would never meet (like in Faulkner’s Wild Palms), separated by a poem. The link would be made through this lyrical element placed at the centre – the element I eventually decided to throw out. These two stories would touch each other for a single moment, accidentally, and this moment would be secondary in relation to the totality of the film.

Imagine another sort of intersection: two films in one, not a film-within-a-film but two distinct movies, one incomplete, the other filling the gaps but revising and correcting the first (The Suspended Vocation, 1977). Or imagine making an art-history documentary that speculates on the possibility of a missing link in the output of an imaginary, mediocre artist (The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting, 1979). How about dismantling the conventions of TV election coverage, to the point where one can no longer discern what candidate won (Of Great Events and Ordinary People, 1979)? Or what if a man assigned to memorize the names of 15,000 political resisters becomes absorbed in recalling visiting a movie house as a child (Life Is a Dream, 1986)? Or perhaps a single actor could play different characters (Three Lives and Only One Death, 1996)?

In their working out, however, these givens often fret and fall away. They are overtaken, or nowadays we might say overwritten, by digressions, anecdotes, accidents, interruptions, abstruse commentary, coincidences, free associations, labyrinthine plot twists (often driven by conspiracies and secret pacts), and Surrealist juxtapositions. The movie house of Life Is a Dream has a toy train running through it. Ruiz’s affinities with Borges and Góngora and Chesterton point to an almost academic fascination with schematic systems, as well as the desire to push them toward absurdity. It’s telling that the poem that was to knot the two strands of Socialist Realism was clipped from the movie.

Narrative binds, but narrative also loosens. It can be a robust oak, but it can also be kudzu. Ruiz understood that what keeps us listening, reading, watching is the promise of a surprise that in retrospect will seem inevitable. The best tragic plot, Aristotle says, is one that makes unexpected things happen within a cogent chain of causality. Ruiz knew our inclinations, but what he gave us were plots of the sort that Aristotle calls episodic–perhaps we should say fragmentary. His plots exfoliate, in both senses of the word: they spread out from a kernel, and they peel off in flakes.

In this respect he turns out to be the realist, and Aristotle the fabulist. Ruiz understood that real-world stories breed like rabbits. Listen to yourself and a friend in conversation, and you’ll find one story calling up another, with yet a third crowding from at a tangent before the first one is finished. In plotting our fictions, we can multiply tales neatly, staking them out in parallel lines or coiling them inside Chinese boxes [4]. But if we take the pressure off, the stories can burst out of control, intertwining or doubling back or sprawling out or just dying off. Feuillade and his contemporaries understood this: A serial could go on forever, because we could plop in a fresh character and create a further adventure. The same thing happens with news on the Internet, spreading and splintering, each version of a story torn apart but also expanded by rehash and critique.

Perhaps we can take some of Ruiz’s abrupt deep-focus shots, blowing up an action or a bit of the set that would otherwise be minor background detail, as a pictorial reminder of the centrifugal impulse of narrative. Anything looming in the foreground hints at the possibility of a new character with a new story. In Three Crowns of the Sailor, while the sailor listens to a tale told by the Blind Man, we are distracted by grotesque glimpses of what unseen others are up to in the bar.

Stories have to end, but nothing at the end can match the arousal of a beginning. Endings usually disappoint. The explanation of an puzzling situation–say, footprints on the ceiling–will inevitably be more prosaic than the premise that sets our imaginations on a wanton chase. (Hence the perfunctory, even arbitrary, resolutions of detective stories.) By contrast, openings refresh us and, as the name implies, “open” things up to crazy possibilities. So why not use the prospect of endless beginnings, perpetual change of situation, to sustain the magic?

What becomes inevitable isn’t a logical resolution, which has to be more or less imposed by tradition. What’s inevitable is a perpetual spawning of characters, plots, and situations. So an apparently stable, albeit fantastic, narrative situation posited at the start may be undermined. Again and again the film seems to start over; the rules keep changing. Ruiz made shaggy-dog stories for cinephiles. He was a formalist who liked unraveling forms.

On the whole I was more an admirer than an enthusiast. I thought Ruiz’s films were imaginative and risky in ways that opened up new horizons. I tried to do justice to his importance in the survey of film history that Kristin and I composed.

Yet here we confront the difference between critical judgment and personal taste [7]. I tended to find each Ruiz film intriguing on an intellectual level, but dry and scattershot as well. For all the prodigious invention, and given his bias toward free-range story breeding, I sometimes thought that the données were underdeveloped. He had wondrous ideas, but I wasn’t sure that he did enough with them. And of course some stretches of his yarns were downright opaque to me.

Still, artists have a way of teaching us how to watch, and rewatch, their work. Maybe now, after having been absorbed by Mysteries of Lisbon for reasons sketched here [8], I’m better prepared to appreciate the legacy of a unique sensibility–one that has already given us the adjective Ruizian. It is a term of praise.

No filmmaker had more zealous proselytizers. His admirers have shown how to blend analytical precision with brio. They make you want to see the films pronto. The Ruiz initiate can start with Adrian Martin’s homage at girish’s site [9]. You won’t read a more sensitive piece of film criticism this year. Next savor James Schamus’ memoir at Filmmaker [10], where he recalls working with Ruiz on his first US film. Proceed to Jonathan Rosenbaum’s posting of one of his classic studies of Ruiz [11], which includes links to other essays.

Now you’re ready for the heady experience of the annotated filmography [12] (complete up to 2004) in the journal Rouge. Both Adrian and Jonathan participated. My quotation about Socialist Realism comes from there [13]. By now you should be on to the films, and perhaps the writings collected in volumes one [14] and [14]two [15]of Ruiz’s Poetics of Cinema.

By chance I commented on Ruiz just a little while ago [16]. And thanks to B. Kite for the note about Ruiz and Harry Stephen Keeler [17], obviously kindred spirits. Mr. Kite sent Ruiz some Keeleriana, which may have influenced what Ruiz says here [18].

Apologies for my tongue-twisting title, which is offered in the spirit of Tres Tristes Tigres.

Mysteries of Lisbon.