Twenty Cigarettes.

DB here:

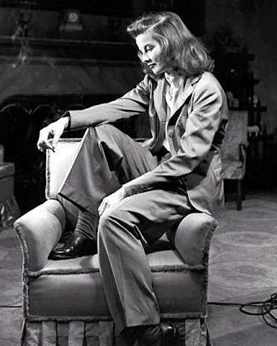

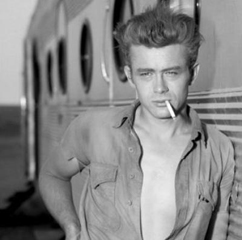

Reflect for a moment on the powerful role played by the cigarette in twentieth-century photographic portraiture. Before our recent worries about lung cancer, why were artists, movie stars, and other celebrities so often artfully posed with a tobacco product? Sometimes the imagery seems to evoke sophistication, presenting the subject as a man or woman of the world.

Or the portrait can suggest a relaxed, informal moment, a cigarette break.

That moment of relaxation can be extended to suggest contemplation or meditation, with the eyes gazing off into the middle distance. Despite the pretty face, this person is deep.

Alternatively, the cigarette can also suggest that painting or writing is a pretty casual affair. Smoking while working, the artist becomes an artisan. Maybe creating masterpieces is no more highfalutin than laying pipe.

And of course there’s the erotic side. A cigarette can make you look attractively dangerous.

In Golden Age studio portraiture, the smoke can become a compositional arabesque.

I’m not suggesting that James Benning set out to subvert this glamourous, stylized tradition in Twenty Cigarettes, which I caught at the Hong Kong Film Festival [13]. But I think his film presents smoking as never seen before–defamiliarizing it, the Russian Formalist literary critics might say. And the movie’s not solely concerned with smoking. It resonates a bit with something I looked into in an earlier entry, on facial expressions in [14]The Social Network [14]. But here the film asks a different question: How expressionless can a face be?

Studied neutrality

A person in a medium shot smokes a cigarette. Repeat nineteen more times, showing smokers who suggest different ethnic and social identities. They are framed against outer walls, gardens, skies, or rooms. As in the Structural Film tradition, we witness an activity whose end is more or less known, and this forces us to study the minutiae of the process. But how much time the shot takes isn’t completely determined. Some smokers smoke faster than others, some shots run longer, and occasionally Benning halts the shot before the cigarette is quite finished.

In each shot, the smoker doesn’t talk and seldom looks at the camera. No one else is visible or audible (except, in one take, a voice distantly shouting, “Fuck you!”) Benning put himself out of sight during the filming of each take. By cutting the smokers off from all social intercourse, the film reminds us that it’s probably more usual for to people smoke while doing something else, like reading or watching TV or talking with friends. Benning forces us to watch the act of smoking in an almost artificially pure state. The film quickly becomes a study in smoking styles—quick non-inhalant puffs, luxuriant drags, little exhalations, slow streams curling out of nostrils. The ciggie is held tipped up in a dainty salute, or jammed between fingers. Solitary smoking becomes a sort of social-science experiment: If you can’t walk around, talk to others, window-shop, or whatever after you’ve lit up, how will you behave?

You’ll behave, Benning’s film suggests, by putting on the most blank expression possible. The portraits of artists and movie stars above use the cigarette to enhance the subject’s attitude–frankness, cool regard, disdain, pensiveness, intellectual seriousness. The cigarette, even the smoke, signifies. Nothing in the cigarette-portrait tradition prepares us for the almost frightening neutrality we see on the faces of Benning’s people. What are they thinking? Are they feeling anything?

It’s rather hard to maintain a poker face in a social interaction. Engaging with others, we spontaneously send signals of interest or mutual understanding, if only through raised eyebrows or a quick smile. But Benning’s lone smokers are eerily blank. Even what might seem to be an expression is often simply the person’s face at rest. (Some resting faces are read as non-neutral, as when an elderly person seems perpetually frowning or hangdog.) In the film, when the person’s expression changes, that’s usually because of the smoking; the twenty people squint or frown or tighten their jaw as they suck or exhale. For once facial movement is divorced from emotional signaling, and the result is a kind of anti- [16]Shirin [16], Kiarostami’s portrait gallery of people caught up (apparently) in spontaneous bursts of emotion.

Benning’s film brings to mind the Warhol Screen Tests, and he has acknowledged the influence. Yet unlike Warhol, Benning gave his people the same specific task to execute. He’s like Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has explained that he got performances from his nonactors by letting them occupy themselves with eating and smoking. Warhol, as I recall, left things up to his performers, and so they might fiddle with props, run through a range of expressions, or simply stare innocently or challengingly at the camera. (To avoid reproduction rights problems, let me just send you here [17] to sample some possibilities. On this page [18] Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait.)

Twenty Cigarettes yields something different from the Screen Tests I’ve seen. Using the cigarette as a constant feature, pulling smoking out of its usual place in our habits and social exchange, denying the tradition that shows smoking as connoting attitudes and emotions in people onscreen, Benning enables us to watch, across some ninety minutes, faces that aren’t dramatizing themselves or sending signals. No stars, these folks, let alone superstars. No narcissism either.

Yes, through dress and hair and demeanor we quickly characterize these men and women by type (housewife, hipster, working man). And each face carries marks of experience we can’t help but wonder about. At times I found myself looking for wrinkles and the other signs of smoking’s skin damage. And yes, the subjects know the camera is there, so to some extent they are posing themselves. Even granting all this, it seems to me that Twenty Cigarettes gives us a disconcertingly pure example of what happens when people make a tremendous effort to show as little of themselves as possible. We get to study what lived-in faces look like when they aren’t participating in social life but are aware that the camera is watching them.

Cigarette pictures, as if you didn’t know: Susan Sontag, Cary Grant, Louis Feuillade, Gary Cooper, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean-Luc Godard, Bette Davis, James Dean, Gary Cooper again, and Marlene Dietrich.

The website Celebrities with cigarettes [19] includes many studio portraits. For examples from the Warhol Screen Tests, go here [17]. On this page [18] Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait. Background on the making of Benning’s film can be found in this interview at Cinema Scope [20]. On MUBI Neil Young provides a stimulating and painstaking analysis [21]of Twenty Cigarettes.

Thanks to J. J. Murphy [22] for discussions about Warhol, the subject of his forthcoming book, and of course to James Benning for his assistance.

Twenty Cigarettes.