Jafar Panahi, May 2010.

DB here:

From Tehran comes the shocking news [2] that Jafar Panahi, one of the finest of Iranian filmmakers, has been sentenced to six years in prison. The sentence also bans him from filmmaking for twenty years, forbids him to leave the country, and forbids him from giving interviews to the press, foreign or domestic. Panahi’s collaborator Muhammad Rasoulof was also sentenced to six years in jail.

This is the next step in a series of confrontations between Panahi and the government. He was earlier arrested for attending the funeral of Neda Agha-Soltan [3], the young woman shot in the 2009 protests. His passport was later seized. Before his most recent arrest he was forbidden to leave the country to attend the Berlin and Cannes festivals [4]. Between March and May of this year he was in prison, during which he undertook a hunger strike. In May he was released on bail.

Since the mid-1990s Panahi has directed several extraordinary films, all explicitly or tacitly critical of aspects of Iranian society. Like his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, he attracted attention with films centering on children, notably The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997). The latter is a fine example of how Iranian directors have merged social realism, unexpected character psychology, and experimental storytelling strategies. The first half shows a stubborn little girl trying to get home from school. On a bus, she gets tired of pretending to be in a film and goes off on her own, with her microphone still attached. The crew tries to track her down, and much of the rest of the action takes place on the soundtrack, as we hear her encounters with street life and the crew’s commentary on what they manage to shoot. Sometimes the sound drops out entirely.

The Circle (2000) shifts to the adult world, illuminating critical moments in the lives of several women as they traverse the streets. Crimson Gold (2003), from a script by Kiarostami, shifts from presenting a crime-thriller situation to providing an unusual view of Tehran’s prosperous upper class. Offside (2006) won attention for its exuberant portraitsof women who disguise themselves as men to watch a soccer match. Panahi remarked drily to the court: “The space given to Jafar Panahi’s festival awards in Tehran’s Museum of Cinema is much larger than his cell in prison.”

The charges and the replies

The Mirror.

The oppression of filmmakers isn’t new, of course. Authoritarian political regimes across film history have banned films and punished their creators. In recent times, the Turkish actor-director Yilmaz Güney was imprisoned several times; while incarcerated, he wrote scripts to be filmed by others. After Devils on the Doorstep (2000), Jiang Wen was banned by Chinese authorities from film activities for some years, as was actress Tang Wei for appearing in Lust, Caution (2007).

But Güney was convicted of civil crimes, although of a political nature; his films were not, as I understand it, explicitly part of the charges. And although Jiang and Tang were punished for their film work, that punishment didn’t include jail time.

Panahi is in an unusually vulnerable situation. He is set to be imprisoned for preparing a film.

The official charges are “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security” and “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” The authorities charge that he and his colleague Rasoulof were “preparing an anti-government film bearing on the post-electoral events” of June 2009, when thousands of Iranians protested the disputed reelection of President Ahmadinejad. “You are putting me on trial for making a film that at the time of our arrest was only thirty percent shot.” Panahi was shooting his film in his home, and government authorities seized the footage.

Other accusations sought to bolster the case. Panahi’s household, according to the prosecution, held “obscene films.” In his defense statement [6] last month, he replied that these were film classics that have inspired him. He was charged with participating in demonstrations, but he replied that he was there to observe, and this was within his rights. He notes as well that he shot no footage of the demonstrations, acknowledging that filming was forbidden. As you know, on-the-spot reportage leaked out through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube [7].

Panahi was accused of making his film without permission, but he responded that there is no legal requirement that a filmmaker obtain permission. He was accused of organizing protests at the opening of the Montreal Film Festival, but there he served simply as the head of the jury. He was charged with giving interviews to foreign media, but he pointed out that there are no laws forbidding someone from being interviewed. He was even accused of not giving scripts to his actors! He explained that he works with non-professional actors, and it’s common for Iranian filmmakers to simply explain what the actor must do and say.

The charges may be simply a pretext for silencing a prominent figure critical of current Iranian society. Panahi’s films do not circulate legally there, and he is widely believed to be in sympathy with liberal forces. The government has sought to eradicate the most visible of these factions, the Green Party. Even Islamic clerics have been swept up in the crackdown. A parallel case to Panahi’s is the attack on Mohammad Taqi Khalaji, a dissident cleric. Last January he was arrested and his computer and papers were seized. He too was incarcerated in Evin prison before being released on bail. Yet he was not formally charged with anything. His personal papers, including his passport, were not returned to him.

You can get some grim satisfaction for knowing that movies still matter in some parts of the world. Films have the power to shock bureaucrats and threaten authoritarian regimes. Instead of being simply “assets” or “content” to be extruded across platforms and shoved through release windows, cinema is in some places taken seriously as political critique.

Panahi’s case, his lawyer asserts, will be appealed.

Out of bounds

Offside.

Lest we Americans savor our superior virtue, consider this: Four months before 9/11, Panahi was traveling between Hong Kong and Argentina and stopped over in New York. He had been told he did not need a transit visa, but he was detained by American authorities at JFK Airport for lacking one. Here is Stephen Teo’s account [9] in Senses of Cinema:

On his way to the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema on 15 April, 2001, after having attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Panahi was arrested in JFK Airport, New York City, for not possessing a transit visa. Refusing to submit to a fingerprinting process (apparently required under U.S. law), the director was handcuffed and leg-chained after much protestations to US immigration officers over his bona fides, and finally led to a plane that took him back to Hong Kong. As far as is known, this incident was not reported in any major US newspaper, even though The Circle was being shown in the United States at the time (another irony: for that film, Panahi was awarded the “Freedom of Expression Award” by the US National Board of Review of Motion Pictures).

We are in the season in which critics are likely to use the word courage casually, as in “Natalie Portman gives a courageous performance in Black Swan.” The ongoing struggle of Panahi and thousands of his fellow Iranians remind us what real courage, in the world outside the movie theatre, looks like.

A petition addressed to Iran’s leaders in regard to Panahi and Rasoulof’’s case can be signed here [10]. For one proposal for how world film culture could respond, go here [11].

A fairly detailed chronology of events around Panahi’s imprisonment can be found on Wikipedia [12]. Panahi’s counter to the official charges, as well as the source of this entry’s title quotation, can be found here [6].

I have so far found no U.S. coverage of Panahi’s treatment in America in spring 2001. A report here [13] from Australia suggests that he was detained but not arrested. Senses of Cinema has published Panahi’s letter to the Board of Review [14] protesting his treatment on that occasion.

The case of Mohammad Taqi Khalaji is discussed here [15] and here [16].

P.S. 22 December 2010: Yesterday Jonathan Rosenbaum posted his June 2001 review of [17]The Circle [17]. It’s an excellent piece, providing both in-depth analysis and broader context, and it does make reference to Panahi’s detention upon arriving in the U. S.

P.P.S. 22 December 2010: Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for a name correction.

P.P.P.S. 26 December 2010: Director Rafi Pitts has published an open letter to President Ahmadinejad about Panahi and Rasoulof’s sentence. Read it here at mubi [18].

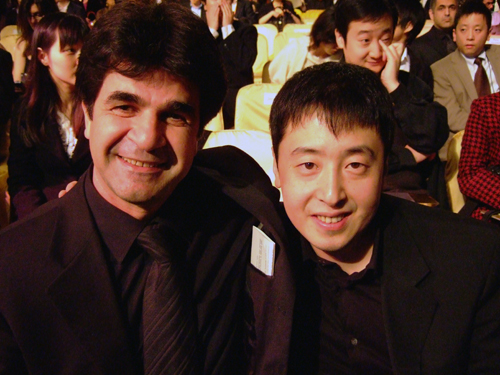

Jafar Panahi and Jia Zhang-ke, Asian Film Awards 2007. Photo by DB.