Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival [2] that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry [4], are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative [5]. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

The theatre of memory

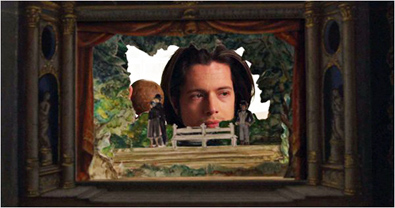

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco [10], a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

[11]Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

[11]Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version [12].

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here [14].

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao [15], a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry [18]. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative [19] and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative [20], as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction [21]. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at [22]Cinema Scope [22].

Oki’s Movie.