Her design for living

Tuesday | March 9, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

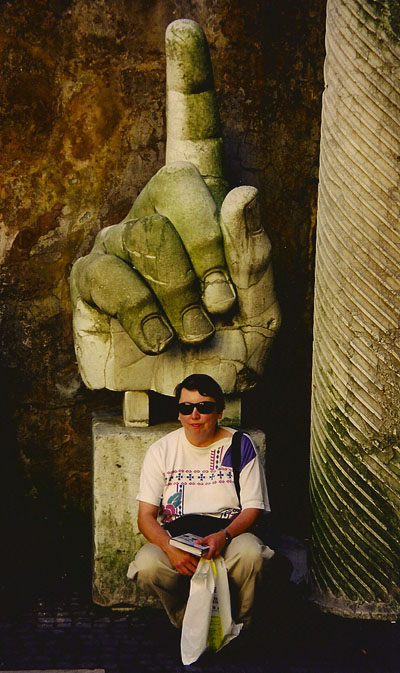

Kristin in Rome, 1997, in front of a “recent” hand from a colossal statue of Constantine. The Amarna statuary fragments she studies are twice as old.

DB here:

Kristin is in the spotlight today, and why not? She’s too modest to boast about all the good things coming her way, but I have no shame.

First, our web tsarina Meg Hamel recently installed, in the column on the left, Kristin’s 1985 book Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934. It was never really available in the US and went out of print fairly quickly. Vito Adriaensens of Antwerp kindly scanned it to pdf and made it available for us. So we make it available to you. More about Exporting Entertainment later.

Second, Kristin is not only a film historian but a scholar of ancient Egyptian art, specifically of the Amarna period. (These are the years of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and their highly unsuccessful experiment in monotheism.) Every year she goes to Egypt to participate in an expedition that maps and excavates the city of Amarna. In recent years she’s focused on statuary, about which she’s given papers and published articles. Now we’ve learned that she has won a Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fellowship to work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection for a month during the next academic year. So at some point then we’ll both be blogging from NYC. Think of the RKO Radio tower sending our signals to a tiny world below.

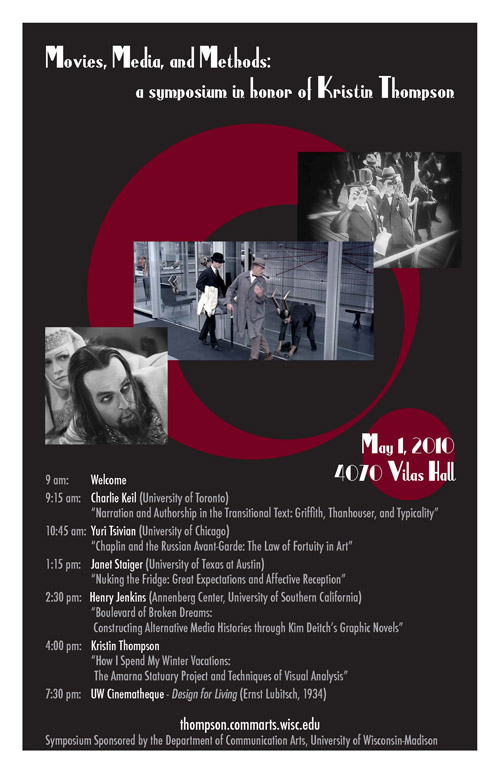

Third, she is about to turn 60, and in her honor the Communication Arts Department is sponsoring a day-long symposium. On 1 May we’ll be hosting Henry Jenkins, Charlie Keil, Janet Staiger, and Yuri Tsivian to give talks on topics related to her career interests. Kristin’s talk will survey her Egyptological work, with observations on how she has applied analytical methods she developed in her film research. You can get all the information about the event, as well as find places to stay in Madison, here.

Kristin came to Madison in 1973, a very good moment. Whatever you were interested in, from radical politics to chess to necromancy (there was a witchcraft paraphernalia shop off State Street), you could find plenty of people to obsess with you. Film was one such obsession.

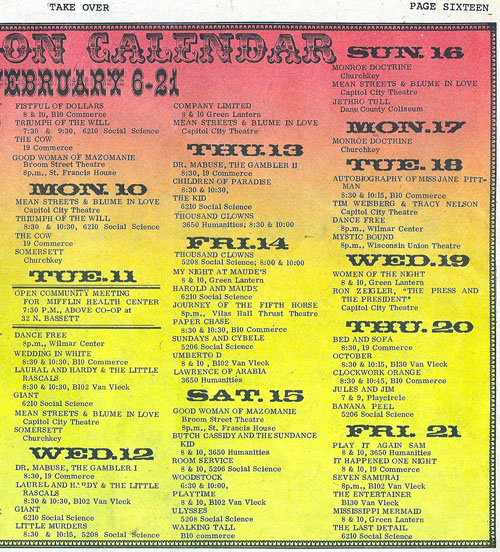

The campus boasted about twenty registered film societies, some screening several shows a week. Fertile Valley, the Green Lantern, Wisconsin Film Society, Hal 2000, and many others came and went, showing 16mm films in big classrooms in those days before home video. Without the internet, publicity was executed through posters stapled to kiosks, and the fight for space could get rough. Posters were torn down or set on fire; a charred kiosk was a common sight. Another trick was to call up distributors and cancel your rivals’ bookings. One film-club macher reported that a competitor had cut his brake-lines.

What could you see? A sample is above. What it doesn’t show is that in an earlier weekend of February of 1975, your menu included Take the Money and Run, The Lovers, Ray’s The Adversary, Page of Madness, Fritz the Cat, The Ruling Class, Dovzhenko’s Shors, Chaney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame, American Graffiti, Wedding in Blood, Pat and Mike, Camille, Yojimbo, Faces, Days and Nights in the Forest, King of Hearts (a perennial), Sahara, The Fox, Day of the Jackal, Dumbo, Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, Slaughterhouse-Five, Mean Streets, A Fistful of Dollars, Triumph of the Will, and The Cow. Not counting the films we were showing in our courses.

In addition, there was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, recently endowed with thousands of prints of classic Warners, RKO, and Monogram titles. (There were also TV shows, thousands of document files, and nearly two million still photos.) When Kristin got here she immediately signed up to watch all those items she had been dying to see. She suggested that the Center needed flatbed viewers to do justice to the collection, and director Tino Balio promptly bought some. Those Steenbecks are still in use.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Out of the film societies and the WCFTR collection came The Velvet Light Trap, probably the most famous student film magazine in America. Today it’s an academic journal, though still edited by grad students. Back then it was more off-road, steered by cinephiles only loosely registered at the university. Using the documents and films in the WCFTR collection, they plunged into in-depth research into American studio cinema, and the result was a pioneering string of special-topics issues. When I go into a Parisian bookstore and say I’m from Madison, the owner’s eyes light up: Ah, oui, le Velvet Light Trap.

Above all there were the people. The department had only three film studies profs–Tino, Russell Merritt, and me–though eventually Jeanne Allen and Joe Anderson joined us. Posses of other experts were roaming the streets, running film societies, writing for The Daily Cardinal, authoring books, and editing the Light Trap. Who? Russell Campbell, John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tom Flinn, Tim Onosko, Gerry Perry, Danny Peary, Pat McGilligan, Mark Bergman, Sid Chatterjee, Richard Lippe, Harry Reed, Michael Wilmington, Joe McBride, Karyn Kay, Reid Rosefelt, Dean Kuehn, Samantha Coughlin, and Bill Banning. Most of these were undergraduates, but Maureen Turim and Diane Waldman and Douglas Gomery and Frank Scheide and Peter Lehman and Marilyn Campbell and Roxanne Glasberg and other grad students could be found hanging out with them. A great many of this crew went on to careers as writers, teachers, scholars, programmers, filmmakers, and film entrepreneurs.

Into the mix went film artists like Jim Benning, Bette Gordon, and Michelle Citron. There were film collectors too; one owned a 70mm print of 2001 and didn’t care that he could never screen it. ZAZ, aka the Zucker brothers and Jim Abrahams, were concocting Kentucky Fried Theater. Andrew Bergman had recently published We’re in the Money, and soon Werner Herzog would be in Plainfield waiting for Errol Morris to help him dig up Ed Gein’s grave. Set it all to the musical stylings of R. Cameron Monschein, who once led an orchestra the whole frenzied way through Intolerance. The 70s in Madison were more than disco and the oil embargo. (To catch up on some Mad City movie folk, go here.)

These young bravos worked with the same manic passion as today’s bloggers. The purpose wasn’t profit, but living in sin with the movies. Film society mavens drove to Chicago for 48-hour marathons mounted by distributors. Traditions and cults sprang up: Sam Fuller double features, noir weekends, hours of debates in programming committees. Why couldn’t Curtiz be seen as the equal of Hawks? Why weren’t more Siodmak Universals available for rental? Was Johnny Guitar the best movie ever made, or just one of the three best?

There was local pride as well. Nick Ray had come from Wisconsin, and so had Joseph Losey, not to mention Orson Welles (who claimed, however, that he was conceived in Buenos Aires and thus Latin American). During my job interview, Ray came to visit wearing an eye patch. It shifted from eye to eye as lighting conditions changed. When he showed a student how to set up a shot, he bent over the viewfinder and lifted the patch to peer in. Was he saving one eye just for shooting?

In the big world outside, modern film studies was emerging and incorporating theories coming from Paris and London. Partly in order to teach myself what was going on, I mounted courses centering on semiotics, structuralism, Russian Formalism, and Marxist/ feminist ideological critique.

Back in placid Iowa City, where Kristin got her MA in film studies and I my Ph.D., we grad students had seen our mission clearly. Steeped in theory, we pledged to make film studies something intellectually serious: a genuine research enterprise, not mere cinephilia. Madison was the perfect challenge. Here cinephilia was raised to the level of thermonuclear negotiation, backed with batteries of memos, scripts, and scenes from obscure B-pictures. Confronted with a maniacal film culture and a vast archive, Kristin and I realized that there was so much to know–so many films, so much historical context–that any theory might be killed by the right fact.

Watch a broad range of movies; look as closely as you can at the films and their proximate and pertinent contexts; build your generalizations with an eye on the details. Our aim became a mixture of analysis, historical research, and theories sensitively contoured to both. The noisy irreverence of Mad City, where a former SDS leader had just been elected mayor and city alders could be arrested for setting bonfires on Halloween, wouldn’t let you stay stuffy long.

Kristin’s work in film studies would be instantly recognizable to humanists studying the arts. Essentially, she tries to get to know a film as intimately as possible, in its formal dimensions–its use of plot and story, its manipulations of film technique. I suppose she’s best known for developing a perspective she called Neoformalism, an extension of ideas from the Russian Formalists. Armed with these theories, she has studied principles of narrative in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. She has probed film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and her sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. And she has examined narrative and style together in her book on Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible and the essays in Breaking the Glass Armor.

Contrary to what commonsense understanding of “formalism” implies, she has always framed her questions about form and style in a historical context. She situates classic and contemporary Hollywood within changes in the film industry–the development of early storytelling out of theatre and literature, or current trends responding to franchises and tentpole films. For her, Lubitsch’s silent work links the older-style postwar German cinema and the more innovative techniques of Hollywood. She situates Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, and other directors in the broad context of international developments, while keeping a focus on their unique uses of the film medium.

Perhaps her most ambitious accomplishment in this vein is her contribution to Film History: An Introduction. She wrote most of the book’s first half, and though I’m aware of the faults of my sections, I find hers splendid. After twenty years of research, she produced the most nuanced account we have yet seen of the international development of artistic trends in American and European silent film.

Kristin has also illuminated the history of the international film industry. Everybody knows that Hollywood dominates world film markets. The interesting question is: How did this happen? Exporting Entertainment provides some surprising answers by situating film traffic in the context of international trade and changing business strategies. One twist: the importance of the Latin American market. The book also opened up inquiry into “Film Europe,” a 1920s international trend that tried to block Hollywood’s power. In all, Exporting Entertainment led other researchers to pursue the question of film trade, and I was gratified to see that Sir David Puttnam’s diagnosis of the European film industry, Undeclared War, made use of Kristin’s research.

More recently, Kristin has turned her attention to the contemporary industry, the main result of which has been The Frodo Franchise, a study of how a tentpole trilogy and its ancillaries were made, marketed, and consumed. Her love of Tolkien and her respect for Peter Jackson’s desire to do LotR justice led her to study this massive enterprise as an example of moviemaking in the age of winning the weekend and satisfying fans on the internet. She maintains her Frodo Franchise blog on a wing of this site.

Most readers of this blog know Kristin as a film scholar. They may be surprised to learn that she also wrote a book on P. G. Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster books. Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; or, Le Mot Juste is a remarkable piece of literary criticism. Here she shows how Wodehouse developed his own templates for plot structure and style. Again, the analysis is grounded in research–in this case, among Wodehouse’s papers. So assiduously did she plumb Plum that she became the official archivist of the Wodehouse estate. This is also, page for page, the funniest book she has yet written.

Her Egyptological work is no joke, though, and she has become one of the world’s experts on Amarna statues. She has published articles and given talks at the British Museum and other venues. Soon she’ll trek off for her ninth season at Amarna. There, joined by her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan, she’ll study the thousands of fragments that she’s registered in the workroom seen above. It’s preparation for a hefty tome on the statuary in the ancient city.

You can learn more about Kristin’s career here, in her own words. These are mine, and extravagant as they are, they don’t do justice to her searching intelligence, her persistent effort to answer hard questions, and her patience in putting up with my follies and delusions. You’d be welcome to visit her symposium and see her, and people who admire her, in action. While you’re here, you can watch a restored print of Design for Living, by one of her favorite directors, screening at our Cinematheque. In 35mm, of course. We can’t shame our heritage.

Poster design by Heather Heckman. Check out our Facebook page too.