Kristin here:

Coming back from a trip has pleasant and unpleasant consequences. Bills piled up, but so did stacks of packages, books and DVDs we forgot we had ordered or ones sent to us out of the blue.

The intrepid companies that rescue and issue silent films on DVD have been busy. All are past winners of awards in the Cinema Ritrovato festival’s annual ceremony, and obviously they are working hard to keep their standards up. (For a pdf listing all the winners since the awards began in 2004, click here [2].) Two of my favorite directors are represented.

Much More Méliès!

In 2008, Flicker Alley won “Best Box-Set” for its monumental collection “Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema” [3] (five DVDs with 173 films). Amazingly, 26 more films (or fragments, in one case very short) have been discovered since its issue. These will be released in the U.S. on February 16 on a single disc titled “Georges Méliès Encore.” [4]

One of these, Le Manoir du Diables/The Haunted Castle, from 1896, contains something like 26 cuts, all stop-motion effects. I wouldn’t have thought such an elaborate production would have been possible so early in the history of cinema, but here it is. It’s also interesting for having been shot outdoors, with what looks like a flat gravel “floor.” The lighting changes dramatically at one point, with the sun in a different position after an obvious pause in filming, and for a time the shadow of a tree is visible in the right foreground. The set is also quite elaborate for such an early production. Watch for a moment when the actors bump into the set and cause it to wobble alarmingly.

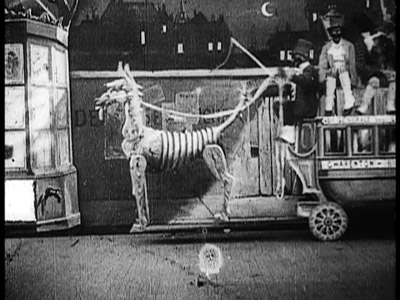

I had long been intrigued by production photos and sketches from a lost Méliès film, L’omnibus des toqués ou Blances et Noirs/Off to Bloomingdale Asylum. (I have no idea why this English title was chosen, since it has nothing to do with the action. “Toqués” would translate roughly as “crazies.”) The thing that intrigued me was a strange, mechanical-looking horse that draws the omnibus of the title. Finally I got to see it, and it was worth the wait. The horse is good, to be sure. It pulls a small coach with five black-face minstrels sitting atop it.

It’s not terribly apparent from the film, but a surviving Méliès sketch makes it obvious that the horse farts, driving the minstrels to jump off. The horse and coach depart, and the four minstrels begin an elaborate game of slapping and kicking each other in rhythm, each blow turning one into a white-clad pierrot figure and then back into a minstrel. It’s another of Méliès’ rapid-fire set of stop-motion substitutions, with the positions of the figures matched with astonishing precision. A tiny masterpiece in one minute and four seconds, counting the title card.

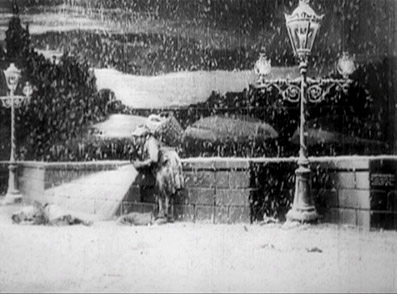

There’s a wide range of genres represented on the disc, including staging of news events, as in Éruption volcanique à la Martinique/ Eruption of Mount Pele (1902); chase films, like Le mariage de Victoire/ How Bridget’s Lover Escaped (1907); and even tear-jerking melodrama, like Détresse et charité/ The Christmas Angel (1904). The latter has an interesting stop-motion effect to add a white-painted stream of light as a rag-picker turns on his lantern to see the little beggar-girl asleep in the snow.

An otherwise surprisingly pedestrian 1905 film, L’ile de Calypso/ The Mysterious Island has one impressive moment, when a giant hand (Polyphemus having been transferred to Calypso’s island) emerges from the dark of a cave to threaten Ulysses (who is a bit hard to see, standing against the rocks at the right of the cave).

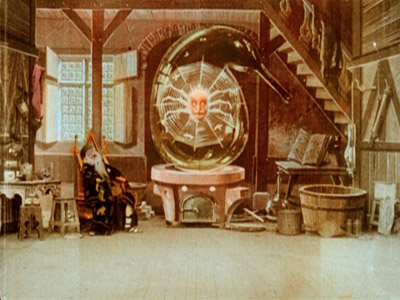

Was Méliès the first filmmaker to realize that leaving a large dark patch in part of set allowed things to be superimposed in that area without looking translucent? The best-known film to use the device is L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc/ The Man with the Rubber Head (1902), but many other films use it, including some on this disc. A few of the films have hand-coloring, including the early L’hallucination de l’alchimiste/An Hallucinated Alchemist, where the alchemist of the title dreams of a giant spider.

The state of preservation naturally varies enormously. One nearly pristine print is the amusing Satan en prison/Satan in Prison (1907). The title is vital, since the bulk of the action consists of a well-dressed man magically producing a series of items to furnish a bare room, culminating in his summoning up a charming lady to share his meal. Hearing the guards approaching, the man reverses the process, ending with a bare room when the two men enter. Finally he is revealed as one of Méliès’ favorite characters, Satan! (See frame surmounting this entry.)

I suppose we shall never have all of Méliès’ films, but there are now more than twice as many known to survive as when I was in graduate school. I look forward to a second encore.

Lubitsch, Lubitsch, Lubitsch

Another pleasant surprise among the heap of packages was Eureka!’s new boxed set of Ernst Lubitsch films from the years 1918-1921. If that sounds a bit familiar, that’s because this is the third such set to appear in just over three years. I’m not going to make a point-by-point comparison, but I’ll sketch some basic differences.

The German set, confusingly titled in English the “Ernst Lubitsch Collection,” came out in November, 2006 and is PAL, region-2 encoded. It contains five Lubitsch silents: Ich mochte kein Mann sein (1918), Die Austernprinzessin (1919), Sumurun (1920), Anna Boleyn (1921), and Die Bergkatze (1921). Its main bonus is a feature-length documentary, Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin—Von der Schönhauser Allee nach Hollywood. None is subtitled. The set won the Cinema Ritrovato’s prize as Best DVD of 2008.

The set was issued by the Munich company Transit Film [9], a government-owned 35mm distributor with a library of about 600 titles, drawn from across the history of German cinema. We’ve brought some of their prints to Madison for Cinematheque [10]screenings. The sources of the films are primarily the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Foundation and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. It also produces documentaries like the one on Lubitsch. (The website offers German, English, and French language options.) It has also put out several DVDs under the name “Transit Classics.” [11]

In the U.S., from late 2006 into 2007, Kino Video brought these five titles out as four individual DVDs (pairing Die Austernprinzessin and Ich mochte kein Mann sein on one disc). Apparently, although Transit’s set didn’t include the 1919 comedy Die Puppe, it made it available, and in December 2007, Kino brought it out on a disc with the Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin documentary—and at the same time issued a boxed set of all six features plus the documentary on five DVDs, called “Lubitsch in Berlin.” [12] (All Kino discs are NTSC region 1; given that they were transferred from PAL versions, they probably run about 4% faster than the Transit versions.)

Eureka!’s set is also entitled “Lubitsch in Berlin.” It contains the same set of films, including the documentary, all also licensed from Transit. These are here arranged over six DVDs. Its unique material is relatively slight, consisting mainly of short original sets of liner notes and an original score for Die Puppe. One advantage is that Eureka!, as usual, has retained the German intertitles and added subtitles to them. (The Kino versions, in contrast, replace the original intertitles with English ones, which has been their practice on some, if not all, of their other DVDs.) Some or all of these intertitles may have been replaced, perhaps reconstructed on the basis of censorship records, as is often the case with restorations. Still, many viewers would want access to the German text as well as the English versions. The Eureka! set is PAL, and it doesn’t seem to have region coding.

For those unfamiliar with Lubitsch’s German films, these are a good introduction. The four comedies all hold up well today. The first three are built around Ossi Oswalda, a boisterous blonde comic who seems to have inspired Lubitsch to move away from broad slapstick to a more stylized, eccentric approach. Pola Negri, after acting such roles as Carmen and Madame Dubarry in the director’s costume pictures, revealed her comic talents in Die Bergkatze, his last German comedy.

Overall my favorite of the group is Die Puppe, so I’m very glad it’s been added. Some might prefer Die Austernprinzessin, which is indeed hilarious. But it mainly has the wealthy heroine’s home as its comic milieu. Die Puppe seems denser, with more characters and three comedy-generating settings: the rich uncle’s home, the art-nouveau cartoon doll shop, and the monastery where the hero takes refuge. Plus there’s the famous prologue, where Lubitsch himself sets up the premise that the characters themselves are simply dolls brought to life. (See below.)

I chose Ich möchte kein Mann sein as one of the best films of 1918. See here [13] for a brief description and a frame at the bottom of the entry.

The conspicuous absence from this set is Madame Dubarry, the 1919 historical epic that made Lubitsch famous worldwide. Perhaps it’s not an ingratiating film at first viewing, but I found that it grew on me in repeated screenings. (I talk about some of its best scenes including one impressive long-take scene, in my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood [15].) Anna Boleyn took on British history in an attempt to replicate the success of Madame Dubarry, but I have never been able to warm up to it. That’s probably partly because Henny Porten simply did not bring the vibrancy to the title role that Negri had in Madame Dubarry and perhaps partly because the increased budget let to an overemphasis on huge sets and crowds of extras (above). The characters in Madame Dubarry seem comfortable in their period costumes; the ones in Anna Boleyn don’t.

I chose Die Puppe as one of the best films of 1919. See here [16]for a frame from it, and one that demonstrates why I admire Madame Dubarry. Perhaps restoration work on the latter is going on at this moment, so that another DVD will someday join these on the shelf.

The other film in the collection, Sumurun, is a quasi-Arabian-Nights tale, starring Pola Negri as a seductive member of a traveling troupe of entertainers. Lubitsch plays his last film role as the hunchback clown who dotes hopelessly on her. The performance isn’t all that different from some of his earlier ones, but perhaps seeing his rather exaggerated acting style in the context of a non-comic film led Lubitsch to doubt his own abilities. Given that he was far better as a director than as an actor, his decision to stay behind the camera was a boon to future generations. To me, Sumurun is fascinating because it shows the first real signs of Lubitsch’s awareness of Hollywood continuity editing, a set of techniques he would thoroughly master over the course of his next half-dozen films.

It can’t have been easy to put together a 109-minute documentary on Lubitsch’s life before his move to Hollywood. In working on my book, I discovered how surprisingly few photographs of him at work onset survive. The studios where he worked don’t survive, though there are shots of the giant Ufa Tempelhof sound stages that now stand where those studios were.

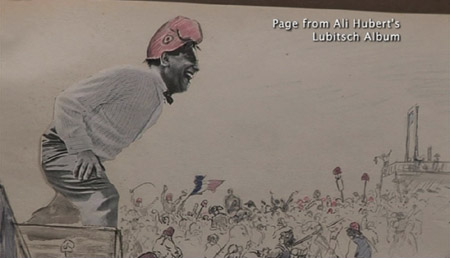

Several prominent historians are interviewed, including archivist Enno Patalas and historian Hans Helmut Prinzler, co-editors of Lubitsch (an extremely useful book, published by the Verlag C. J. Bucher i 1984) and archivist Jan-Christopher Horak (whose master’s thesis was on Lubitsch’s relation to Ufa). Lubitsch’s surviving family members, seen above at the unveiling of a “Lubitsch lived here” plaque, were interviewed: his niece Evy Bettelheim-Bentley (left), granddaughter Amanda Goodpaster (center), and daughter Nicola (right). Lubitsch’s theatrical career is well covered, and generous clips from the pre-1918 era demonstrate his move into comic acting for films. Audio interviews with Henny Porten and Emil Jannings include a charming anecdote she tells about how apologetic Jannings was after the scene in Kohlhiesels Töchter in which his character jerks a bench out from under her–an incident that left her with a bruised rump. In between scenes, directors who have been awarded the Ernst Lubitsch prize, such as Tom Tykwer, discuss the master. Perhaps the most interesting artifact shown is an album Lubitsch’s regular costume designer and friend Ali Hubert made for him, combining drawings with photos of Lubitsch and little poems; below he depicts Lubitsch directing Madame Dubarry. Ultimately Hubert gave it to the director as a gift.

The documentary feels a trifle thin at times, and it makes no real attempt to cover Lubitsch’s Hollywood career, presumably because of the difficulty of getting permission to use clips. But it certainly would be a useful teaching tool for introducing students to Lubitsch’s life before Hollywood.

(Thanks to Ben Brewster for helping determine some of the differences among these three Lubitsch boxes.)

The Man with a Movie Camera before The Man with a Movie Camera

In 2007, the Cinema Ritrovato awarded the “Edition Filmmuseum” series from the Filmmuseum Munchen its DVD award for “Best Series.” We’ve mentioned this series before, in relation to its Walter Ruttmann disc [19] and its DVD of Robert Reinhert’s Nerven [20].

Now the Filmmuseum has issued a two-disc set offering two of Dziga Vertov’s silent feature documentaries, A Sixth Part of the World (1926) and The Eleventh Year (1928). The former is a poetic look at the various and farflung ethnic groups within the U.S.S.R., the population of which made up one sixth of the world. It was the first of Vertov’s films to be strongly praised, seeming to justify his theory of the Kino-Eye.

Those expecting anything as experimental as Man with a Movie Camera might be disappointed. There are some of the familiar camera tricks, such as split-screen effects:

The typography of the intertitles reflects the constructivist style of the 1920s:

The discs have optional English subtitles.

Having seen these films during my research, I haven’t watched the discs in their entirety. The quality looks as good as can be expected. Michael Nyman’s music is certainly not authentic to the period, but what I heard of it sounded strangely appropriate to the images and effective as accompaniment.

The discs also include an interesting bonus, a German propaganda short, Im Schatten der Maschine, by Albrecht Viktor Blum, which used footage from The Eleventh Year to make a film critical of the technical progress which Vertov was praising in his own movie. (Since The Eleventh Year had not yet appeared in Germany, Vertov was actually accused of plagiarizing from Blum rather than the other way round.)

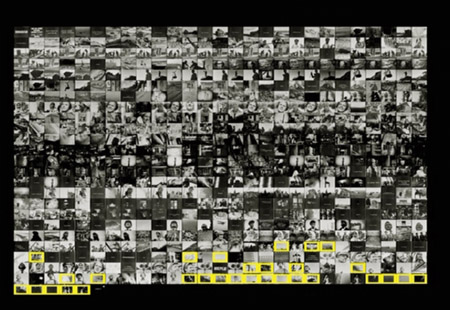

Another bonus is a 14-minute documentary, Vertov in Blum: An Investigation (optional German or English narration). This fascinating short begins by demonstrating that Vertov himself and possibly others almost certainly cannibalized footage from The Eleventh Year for Man with a Movie Camera and other films. It goes on to hypothesize that the final montage in Im Schatten der Maschine may consist of footage that Vertov later removed from The Eleventh Year‘s negative. Side by side comparison of prints using Final Cut Pro revealed matching shots between the two films, highlighted in yellow here:

Blum’s film culls shots and even edited passages primarily from late in Vertov’s film, but it continues beyond the end of the surviving version of The Eleventh Year. Some of those shots have been traced to other, later Vertov films, and the archival sleuths are still comparing prints and looking for the rest. They may have found the missing ending from The Eleventh Year; at least, the evidence makes that idea very plausible. Whether they are right or not, though, the short demonstrates the painstaking work often necessary in the restoration of films.

These companies and archives have certainly not been resting on their laurels. It will be exciting to see what the upcoming Cinema Ritrovato’s awards will highlight.