DB here:

Today, I offer more on cognitive film studies, the activities of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image [2], and why both matter. For background, visit the previous post and here [3] and here [4]. Throughout, I’ll harken back to the issue of convergent audience responses: How can viewers from different cultures grasp certain appeals that films provide?

This research tradition seeks to answer questions about moving-image media, especially questions of an artistic nature. The researchers examine filmmaking with the assistance of findings and theoretical frameworks that have emerged in the cognitive sciences of psychology, anthropology, and other disciplines. Some specifics:

Cognitive film studies emphasizes explanations over interpretations. Explanations can be causal (what made this happen) or functional (pointing out the purposes that something fulfills). When human action is part of what we’re studying, the explanations tend to involve goals and motives, means and ends. By contrast, a lot of humanistic media study emphasizes interpreting films but leaves causal and functional processes unexamined.

This research tradition is mentalistic. In explaining viewers’ responses, it looks first to features of the human mind. This doesn’t mean that researchers study minds cut off from society; rather, the emphasis is on the mental activities tied to all sorts of experience, including social action and interaction.

This tradition is naturalistic. The explanations it mounts try to fit in with current understanding of human capacities as analyzed by the social sciences. That entails that psychoanalysis, another mentalistic theory of human action, has not on the whole proven a source of reliable explanations. Some cognitively inclined researchers would add that psychoanalytic inquiry has been fruitful for pointing to areas of behavior that answer to naturalistic investigation.

The line of argument, accordingly, is that of rational inquiry, induction and deduction. It stands in contrast to much current film theory, which consists of more or less free association and the rote citation of major thinkers. Cognitive film theory tries to formulate clear-cut questions and to seek answers that have empirical grounding and conceptual coherence.

The tradition has a strong tendency to look for cross-cultural regularities among artworks and viewer experiences. The sources of these regularities need not be innate in any strong sense. Critics sometimes claim that cognitivists believe that everything is “hard-wired,” but virtually no cognitivists say or believe that. For one thing, our “wiring” changes at certain critical periods, especially two months, nine months, and four years of age. Moreover, the regularities in behavior we notice occurring across cultures or social milieus may have come into existence for many contingent reasons. That doesn’t make them any less interesting as explanatory factors.

For example, no culture is without fibers to bind things, but we shouldn’t expect to find a “string” gene or neuron. In this case, and many others, humans equipped with some common faculties and faced with common demands have found common solutions. We can study shared strategic behaviors without committing ourselves to biological determinism.

People who believe in the cultural construction of nearly everything appeal to learning as the means by which cultural processes shape individual action. Yet cultural constructivists have on the whole been unable to specify how learning is possible. Since an utterly vacant mind could never actively pursue or acquire or organize knowledge, we’re obliged to consider that some innate propensities are in place before humans make contact with the manifold of experience. No one needs to teach a newborn to pick out moving objects or synchronize lip movements with sound patterns.

Moreover, if you rest your case on the metaphor of construction, you need to specify the materials out of which action is built. Up to a point you can say that there are cultural constructions out of other constructions and so on. But the system has to get started somewhere. You have to be able to see color before you can learn that stoplights and stop signs are red. Ingrained capacities and tendencies are the best candidates for being the stuff out of which various cultural conventions are constructed.

Most cognitivists hold to the post-Chomskyan view of learning as the unfolding and refinement of innate predispositions and mental structures. In order to learn something, you need to know something else. In fact, a lot else. It now seems overwhelmingly evident that humans come into the world with many predispositions, some broad and vague, some quite concrete. Some of these are primed in the womb, as with a newborn’s preference for mother’s smell. Other predispositions require only a few confirming encounters to be locked in. A baby is sensitive to a certain range of phonological and prosodic patterns, and so she is ready to fasten on those characteristic of a specific language. Babies seem as well to have an intuitive physics; they are surprised when objects disappear or turn into something else. Babies also are sensitive to eye contact and smiling, both crucial to social interaction and reading others’ intentions.

In sum, the most plausible learning model is that of predispositions, often sometimes quite narrowly constrained, that are confirmed and fine-tuned by the environment (often within a critical period of exposure). We need active engagement with the environment, both physical and social, to let our intrinsic capacities develop to their full strength. Nature [5]via [5] nurture [5], as Matt Ridley likes to say.

One implication for film is that humans would be likely to recognize film images without extensive training or even a lot of exposure. (Sermin Ildirar found this in the village study mentioned in my previous post). Some understanding of the actions and emotions we see onscreen may have quite specific neural sources, with “mirror neurons” as currently good candidates for grounding recognition and empathy. Other patterns of storytelling and style could be quickly learned, as they piggyback on our understanding of real-world knowledge of social interactions.

Having a battery of predispositions would make sense in evolutionary terms. We gain survival advantage by coming into the world ready to have our biases fine-tuned by experience. Increasingly, for some researchers, the puzzles of cinematic convergence and divergence find their ultimate explanations in human biological and cultural evolution.

Booked

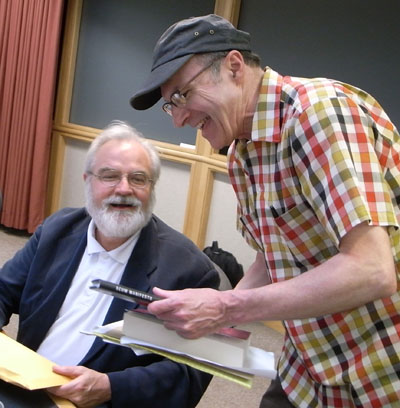

Noël Carroll and JJ Murphy, SCSMI convention June 2008.

I try never to take the present moment as a culmination or turning point in anything. Yet I can’t help noticing that the tenets of cognitive film studies chime in with three wider trends in our current intellectual life.

First, there is a burst of interest in the psychology of informal reasoning. A host of books talks about the shortcuts, heuristics, and predictable errors we make in everyday actions. Examples would be Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made, Ori and Rom Brafman’s Sway, Gary Marcus’s Kluge, Jonah Lehrer’s How We Decide, Joseph T. Hallinan’s Why We Make Mistakes, and Dan Zariely’s Predictably Irrational. The flourishing area of behavioral economics, typified by Akerlof and Shiller’s Animal Spirits, is an outgrowth of this line of inquiry. Most of these books explore the cognitive biases that were brought to light by psychologists some time ago, but now emotion is seen as playing a central role.

A second thread in the cultural conversation involves neurology. Now that brain scanning has yielded more precise ways of tracking mental activity, our common-sense actions are seen to have surprising and tangled roots. Many of the books just mentioned draw upon neuroscience to identify the sources of cognitive biases. A rich survey of the neurological territory as currently mapped can be found in Human: The Science Behind What Makes Us Unique [7], by Michael Gazzaniga.

Then there’s the hottest topic of all, a renewed interest in evolutionary biology. A host of books is rolling out explaining and debating Darwinism. (By the way, Charles, happy centenary.) A good recent example is Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True [8]. But the interest in evolution has given a new salience to evolutionary psychology, that area of inquiry that investigates how our minds have been shaped and constrained by adaptation and other evolutionary processes.

Evolutionary psychology came to prominence in the social sciences with the 1992 breakthrough book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture [9]. There Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby flung down a challenge to traditional social science. Most researchers assumed that the mind was plastic and variable to a very large extent, both between cultures and within an individual’s lifetime. Culture held an irresistible sway over mental life. The essays collected in The Adapted Mind, particularly Tooby and Cosmides’ introductory manifesto, suggested that psychologists needed to consider evolution as a powerful source of explanations for mental activity. Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate [10] (2002) brought this line of thinking to a much broader public.

Although many humanists are proud of owing nothing to science, it’s curious that they often share traditional social sciences’ belief in a more or less blank slate. Virtually everything is culturally constructed; any biological givens are written off as nonexistent, unimportant, or uninteresting. But some humanistic scholars are starting to show that such factors possess both interest and explanatory value.

Studies linking art and literature to biological and cultural evolution are enjoying great prominence this year. Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct [11] and Brian Boyd’s On the Origins of Stories [12] have sparked a wide discussion of how the play instinct, mate selection, and other adaptations might shed light on narrative, music, and the visual arts.

Now, when cognitive and evolutionary models are the latest thing in literary studies, to be applauded or denounced by the MLA rank and file, it’s worth remembering that film studies has been plowing this field for quite some time. Some people would say that my Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) opened up this wing of film studies, but although that book drew on current developments in cognitive psychology, it didn’t outline a broad research program.

More far-reaching was Noël Carroll’s “The Power of Movies,” also published in 1985. Carroll’s seminal essay laid out a concise explanation of cultural convergence through cinema, or as he put it, how “movies have engaged the widespread, intense response of untutored audiences throughout the century.” Carroll’s critique of then-current film theory, Mystifying Movies [13] (1985 again), developed the essay’s idea as a counterweight to psychoanalytic and neo-Marxist explanations for the power of popular cinema. The importance of attention, the role of visual techniques in shaping uptake, and the possibility of evolutionary sources for cinema’s appeals—these and other themes of today’s cognitive film research can be found in Carroll’s work of twenty-five years ago. I suppose that “The Power of Movies” is the cognitivist’s equivalent to Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

A turning point?

Joe, Barb, and Amy Anderson; SCSMI convention, June 2008.

Grand Theory in the humanities has prided itself on being cutting edge, yet it has ignored virtually all of the major developments in the human sciences, from Chomskyan linguistics through cognitive science and now evolutionary and neurological research. That ignoral can seem almost wilful. The 1990s saw a flourishing of cognitive film theory, such as Ed Tan’s study of emotion in cinema [15] and Murray Smith’s study of characterization [16]. Yet in 2006, when I was invited to London to give a paper surveying the perspective, I seemed to be speaking Martian. Two of the most distinguished senior film scholars in the UK said they couldn’t really comment adequately. The approach was all so new and unfamiliar!

If I had been haughty enough to offer two veterans of Screen some reading tips, I could have referred them to two compelling overviews. Paul Messaris’s [17]Visual Literacy: Image, Mind, and Reality [17] (1994) synthesized psychological and anthropological research on how people responded to media and concluded that there wasn’t yet any evidence that images and their normal combination were radically coded. Joseph Anderson’s [18]Reality of Illusion [18] (1998) showed how key questions of cinematic perception and comprehension have been addressed by empirical research in the social sciences. Joe and his wife Barbara were also pioneers in bringing evolutionary explanations to bear on cinematic problems, thanks to James J. Gibson’s “ecological” frame of reference.

In just the last year, three of the people deeply involved with SCSMI have published books that push the conversation in fresh directions. Assume that widely distributed propensities, either innate or converging through cross-cultural regularities, get fine-tuned by the specifics of cultural experience. How do these convergences and divergences emerge in films?

[19]The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures [20] (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film [21] (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

[19]The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures [20] (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film [21] (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

On both fronts, the book tries to balance the convergence/ divergence tendencies. Take My Neighbor Totoro.

The film is clearly influenced by its Japanese origin, from the use of Shinto gods to the rice fields and sliding doors. But the fact that children all over the world are fascinated by the film is only loosely related to those cultural specificities. . . . Miyazaki uses a series of devices that tap into innate and universal mental mechanisms and emotions. Central, of course, is the fascination with the soft, organic counterintuitive agent Totoro, who provides attachment security and empowerment for the little girl, Mei, in the absence of the parents.

Torben goes on to discuss how Miyazaki exploits our interest in “counterintuitive” phenomena, like ghosts and gods, in the figure of a cat who is also a bus.

[22]While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga [23]’s [23]Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience [23] (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions [24], surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

[22]While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga [23]’s [23]Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience [23] (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions [24], surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

Perhaps more interesting, Carl suggests that while sympathetic narratives evoke compassion and pity, distanced narratives evoke cooler feelings, like respect or disdain. This distinction allows him to deny that the common claim that the aesthetic distance we find in Antonioni or Angelopoulos is unemotional; these artists simply deal in different emotions. The distinction also enables him to puncture the belief that Hollywood offers only sentimental hogwash.

It might be thought that sympathetic narratives are the norm in Hollywood. Yet distanced narrative is pervasive in Hollywood, as it is in the “art” cinema. The distanced mode rejects the evocation of strong sympathy for characters—sympathies that are sometimes dismissed as sentimentality—in favor of a more distanced, critical, sometimes humorous, and occasionally cynical perspective.

Plantinga’s examples are action films like The Hunt for Red October, which evokes admiration for gallant stoicism, ironic comedies like Raising Arizona, and puzzle films like House of Games and The Usual Suspects.

One of Carl’s key points is that sympathetic narratives must evoke some negative emotions, when their characters are hit by misfortune. So melodrama is the sympathetic narrative par excellence. Moving Viewers closes with a sensitive discussion of how a film can orchestrate negative emotions in complicated ways, focusing on disgust as it is evoked in films as different as Mask and Polyester.

[25]A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination [26] (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry [27]. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories [28] is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

[25]A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination [26] (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry [27]. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories [28] is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

Understanding Indian Movies shows how those universal plot structures gain richness and emotional force through their encounter with Indian traditions and current social conditions. For example, the sacrificial plot found in all cultures is particularized in Santosh Sivan’s The Terrorist. The film transforms the standard plot for the sake of ideological point and emotional force, modeling its suicide-bomber tale on the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. “The contemporary history depicted by the film was already emplotted in a prototypical narrative form by the people who made that history.”

Hogan’s book is not as localized in its concerns as the title might imply. It’s not only about how to watch Indian movies but also about how to do cognitive studies of media. For instance, Patrick often pauses to criticize over-simplified evolutionary explanations, and he urges that such explanations be used cautiously. But he nonetheless defends the overall convergence/ divergence perspective.

On the one hand there is particularity—not merely the particularity of national cultures, but the particularity of regions, religions, castes, classes, philosophies, ages, and so forth, all the way down to individuals. On the other hand, there is the common genetic heritage of the human brain, the common principles of childhood development (beyond genetics), the recurring practices that arise from group dynamics—a whole series of universal principles that we all share. . . . Whether we are European, Chinese, African, or Indian, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, or Muslim, it is these universals that make it possible for us to understand Indian movies and to appreciate them, rather than merely drawing abstract inferences about them, as if they were part of some inscrutable puzzle.

The differences among these books are considerable. Grodal wants explanations at the level of neurology. Plantinga, of a philosophical temper, wants to clarify the concepts we use to talk about emotions in our experience of films. Hogan is constantly looking for the political implications of artistic choices. But such a range of emphasis matches the variety of the papers assembled for our next meeting.

The Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image meets next week in Copenhagen. Patrick Hogan, alas, will not be joining us. But Torben Grodal is speaking on “Crime Fiction from a Biocultural Pespective,” and Carl Plantinga is giving a talk called “Models of Real and Hypothetical Spectators.” Once more, a complete list of papers can be downloaded here [29].

In sum, evidence is mounting that the SCSMI is now the gathering point for a very robust, accessible, and exhilarating approach to thinking about how films work and work upon us—all of us.

Research conducted by SCSMI members is available in The Journal of Moving Image Studies [30] and in Projections [31].

Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies” can be found in his Theorizing the Moving Image [32] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 78-93. He revisited these ideas in the 1996 essay “Film, Attention, and Communication: A Naturalistic Perspective,” available in Engaging the Moving Image [33] (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 10-58. Some SCSMI members will be represented in the forthcoming Evolutionary Approaches to Literature and Film: A Reader in Science and Art (Columbia University Press), edited by Brian Boyd [34], Joseph Carroll [35], and Jon Gottschall [36]. Evolutionary Psychology [37], by Robin Dunbar, Louise Barrett, and John Lycett provides an excellent survey of several of the ideas I gestured toward today.

Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).