Virginia Theatre on our minds

Saturday | May 2, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Left to right: Kristin, unidentified ardent moviegoer, Erik Gunneson, and Meg Hamel.

Kristin here–

A year ago, those of us attending Roger Ebert‘s Film Festival were forced to do without the presence of the moving force at the center of this lively annual event. Still in therapy from his health crisis of 2005, Roger fell and broke his hip. Characteristically, he struggled to convince his doctors that he could take an ambulance to Champaign/Urbana, but their caution prevailed.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Roger went onstage at intervals during the festival, and he made his first appearance to introduce the opening night’s film, the director’s cut of Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music (1970). Thanks to dedicated software, Roger tapped out messages on a laptop and pushed a button. A voice with a British accent conveyed his words of welcome to us and to director Michael Wadleigh. Then Roger retired to the back of the theater, where a comfy chair is reserved throughout the festival for him.

Michael Wadleigh, Jocko Marcellino, and Dale Bell discuss Woodstock.

From the perspective of nearly forty years, Woodstock has become both a record of remarkable musicians in their prime and a valuable document of the youth culture of the late 1960s. I was a junior at the University of Iowa at the time of the concert, only about five months away from taking my first film course and changing the direction of my education from tech theater to cinema studies. Working on props and make-up for productions every night, I was only dimly aware of the concert or the film that followed.

I also admit I don’t know much about pop music. I kept asking David “Who’s that?” Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Joe Cocker, and others were just names to me, not people whose appearance or music I recognized. But I could appreciate the remarkable way in which the filmmakers were able to capture live performances: the fluidity of multiple, 16mm cameras filming onstage only feet from the performers, the maintenance of focus even when events were recorded at night in less than ideal lighting conditions, and the excellent sound recording.

The screening heralds the release of the new version on DVD on June 9. Amazon has it on pre-order in 3-disc Blu-ray and DVD boxes, as well as a 2-disc set. The third disc has some making-of featurettes and about two hours of additional concert footage left out of even this extended version. I can’t imagine anyone who wants a compilation of performances by this remarkable group of musical talent settling for the smaller set.

Von Sternberg and Jannings, round one

The Alloy Orchestra has become a fixture at Ebertfest. This year’s silent film was Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command. I hadn’t seen it in thirty years or more, and it’s better than I remembered it being. Of course, seeing a gorgeous print on the big Virginia screen with an excellent musical accompaniment does it more justice than an old 16mm copy. Von Sternberg’s images were luminous, and his depiction of silent filmmaking as accurate as anything you’ll see on the screen.

In von Sternberg’s autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, he spends most of the six pages devoted to The Last Command badmouthing star Emil Jannings, with a brief sidetrack to badmouth William Powell. Presumably he’s talking about their behavior on the set, since their performances are both impressive, with Jannings emoting away and Powell as stone-faced as Buster Keaton. Von Sternberg reports that he and Jannings vowed never to work together again. Maybe winning the first Academy Award as best actor changed Jannings’ mind, for a few years later he invited von Sternberg to direct him and Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. The rest, as they say, is history.

Drawing on their usual range of odd percussive objects, including a bedpan, the Alloy group provided a lively score. With Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips as moderator, Guy Maddin and I joined the orchestra members for a discussion afterwards. One of them hinted to me backstage that a score for Docks of New York might be in the offing, which would round off the von Sternberg series perfectly.

Saturday matinee

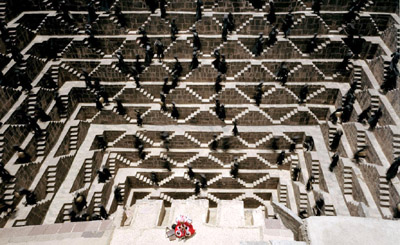

Last year the festival presented Tarsem Singh’s The Cell, with its delirious production design by Eiko. Tarsem’s 2008 follow-up, The Fall, got less attention in theatres, not having a star like Jennifer Lopez to carry it with audiences. It’s a complex fantasy set in a hospital during the silent-cinema era. There a suicidal, injured stuntman telling the tale of a band of mythical heroes bent on revenge to a seven-year-old girl with an arm cast. Her visions of the narrated events, set in spectacular landscapes and exotic buildings, mutate as she insists on changes in the story. The Fall was distinctly a crowd-pleaser, at least for the indefatigably enthusiastic audience in the Virginia Theater. Its Romanian child star, Catinca Untaru, is now twelve, and she proved an articulate charmer as she answered questions after the screening.

Ramin Bahrani with Catinca Untaru and her family.

The next film was Sita Sings the Blues, a marvelously imaginative animated feature by Nina Paley. I had seen the film two weeks earlier at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it was a treat to see it on the big screen again. It’s available for download in various formats here. I had the pleasure of moderating the discussion afterward, and I like the film so much that I’ll be blogging on it separately, including a transcript of the Q&A.

Tattling and bullying

DB here:

A Belgian friend, the late Michel Apers, admired American films above all others. One of the reasons, he explained, was that our films analyzed our political system with uncommon clarity. No other national cinema, he claimed, focused so insistently on the mechanisms and purposes of government, on the duties of citizenship, and on the dilemmas of public life. Not wanting to seem too chauvinistic, I said that we often failed to fulfill our nation’s ideals. “Of course,” he said. “But at least you have ideals. And your films show that it is not easy to live up to them.”

Michel’s remarks reminded me that we do have a tradition of politically critical films: 1930s films opposing lynching and hate groups, 1940s films about political corruption, still later movies like Twelve Angry Men and The Best Man and The Manchurian Candidate. Directors who contributed to this tradition include John Ford (Young Mr. Lincoln, The Last Hurrah), Otto Preminger (Advise and Consent especially), and Alan J. Pakula (All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, Rollover, The Pelican Brief).

Rod Lurie’s favorite film is All the President’s Men, which ought to tell you where his heart is. He made The Contender (2000), a subtle drama about a woman nominated for Vice-President. It has the trappings of a political thriller (the conspiracy at its heart echoes Chappaquiddock, as well as Blow-Out), but that’s just the bait for its serious questions. Graced by a warm but steely performance by Joan Allen, The Contender asks whether a woman in politics is held to a higher standard of sexual conduct than a man would be.

I thought of Michel Apers’ remarks when I watched Lurie’s Nothing But the Truth (2008) at this year’s Ebertfest. The plot revolves around a reporter, Rachel Armstrong (Kate Beckinsale), who outs covert CIA agent Eric van Doren (Vera Farmiga, her of the admirably crooked smile). Rachel refuses to divulge her source and goes to jail. Again, there’s a mystery to draw us through the plot: Who is the source? But more important is the problem of whether a reporter should be forced to name sources in a case that breaches national security. It’s the sort of issue that Preminger or Pakula would have loved to tackle.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

While the debate plays out, Rachel languishes in jail, her family and career dissolving. The case has some analogies to the Valerie Plame incident, but Lurie stressed that the film takes on a similar situation but not comparable characters. He was inspired as much by Susan McDougal’s tenacious loyalty to Bill Clinton.

The film’s secret about Rachel’s source is no mere Macguffin. It provides a powerful supplementary reason for Rachel’s silence, yet it doesn’t wholly excuse it. The film’s last scene leaves you wondering whether Rachel exploited her source. The film’s last shot suggests that she’s wondering too. That shot also wraps up a visual motif that hangs Rachel’s face on one extreme edge of the 2.40 frame, making her look precarious and vulnerable.

All in all, Nothing But the Truth is a sober, unsensational, gripping film about the press’s rights and obligations. It’s not surprising that Lurie was a professional journalist. During the Q & A, the questions were probing and he responded with rapid-fire, well-shaped sentences. There was good humor as well. After Lurie promised to tell us who slept with whom on the shoot, he paused and said: “All I’ll say is that Alan Alda was a complete slut.”

The opportunity for ordinary moviegoers to talk with such gifted and committed filmmakers makes Ebertfest one of the great film festivals on this continent. Roger’s urge to communicate with as many people as possible naturally inclines him toward creating communities, and the folks who gather annually in the Virginia Theatre form one of the most genial and generous group of movie lovers I’ve ever encountered.