Lai Man-wai and Lai Buk-hoi. Photo from Hong Kong Film Archive Collection.

DB, still in HK:

The Hong Kong Film Awards will be celebrating 2009 as the centenary of Chinese film. Why this year? It’s long been said that the first local film was Stealing a Roast Duck, shot by a Chinese director and produced by an American film entrepreneur in 1909. Following received opinion, my book Planet Hong Kong claimed it as the first as well.

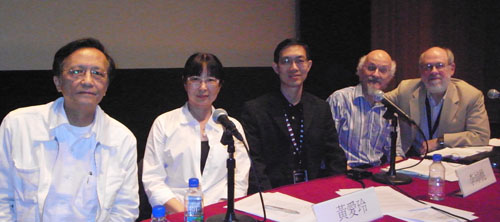

Which only illustrates the maxim that history will not repeat itself, but historians will repeat each other. The Hong Kong International Film Festival mounted a panel around several questions. Is it justified to claim 1909 as the start of Hong Kong cinema? Is Stealing a Roast Duck truly the first film? More ominously, did Duck exist at all? What follows are my interpretations of what the panel, moderated by Li Cheuk-to, came up with.

Law Kar, senior historian of Hong Kong cinema, and Frank Bren, an Australian actor/writer, have diligently pursued the Roast Duck question as part of a larger inquiry into the career of Benjamin Brodsky (erroneously called Brasky or Polasky) who later Americanized his surname to Borden. You can read earlier results of their research in their 2004 book Hong Kong Cinema: A Cross-Cultural View [2]. There they review Brodsky’s filmmaking in China and Japan, but they’re cautious about the claims about his 1909 films. Stealing a Roast Duck “has been recorded as the first commercially made ‘Hong Kong film’ by a Chinese director. . . . Unfortunately, due to the non-discovery of any reports about filmmaking in China in any contemporary newspapers from Hong Kong or Shanghai, [Brodsky’s] story remains partly ‘mythic’ . . . .’ (pp. 37, 43).

At Sunday’s panel, Law and Bren reviewed their most recent research. Law noted that Roast Duck enters film historians’ writings quite a bit after the fact. The crucial mention comes in an article in Cinema Almanac of China 1927, published in Shanghai. Even that article did not specify that Roast Duck was filmed in 1909, only that it was one of four films made by Brodsky’s company, which was founded that year. Law went on to trace how later print sources, mostly books and survey articles, elaborated on these points. By 1936, Roast Duck was said to be one of two 1909 films produced by Brodsky in Hong Kong. Later historians recast the claims again, promoting Roast Duck to the status of Hong Kong’s first story film.

The problem is that there appear to be no contemporaneous sources that can resolve the matter. Law, Bren, and other scholars have found no advertisements, announcements, catalogue listings, or other print documents in 1909 mentioning Roast Duck. Moreover, a 1916 interview with Brodsky, conducted by no less a figure than George S. Kaufman, makes no mention of the film. Brodsky mentions The Empress of Dowers (probably The Empress Dowager) and The Unfortunate Boy , two films he made in China, but gives no specific year of production. Since the piece was written to promote Brodsky’s most recent efforts, it would have been in his interest to play up any pioneering role in Chinese cinema he might have had.

Frank Bren’s presentation was a fascinating detective story. Bren has chased Brodsky through the Internet, Social Security records, city directories, and many other data sources. The efforts yielded the outlines of the remarkable story of a Russian-born American who went to Asia in hopes of setting up film businesses there. Brodsky evidently did produce a Hong Kong film, Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife (1913 or 1914), which involved local filmmakers Lai Buk-hoi, Lai Man-wai, and Lo Wing-Cheung. Chuang Tzu is sometimes considered the earliest true Hong Kong fiction film.

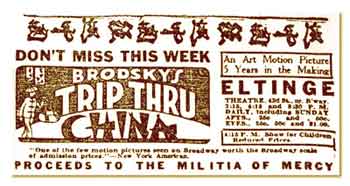

Brodsky was also a documentarist, making two feature-length travelogues, A Trip through China (1916) and Beautiful Japan (1917). He died in 1960 in California. Bren continues to research this colorful figure, being especially fascinated by Brodsky’s unpublished autobiography.

The upshot of this research? There is no positive or direct evidence that Stealing a Roast Duck was made in 1909 or was the first Hong Kong film.

Perhaps it was not made at all? Wong Ain-ling, Research Officer at the Hong Kong Film Archive, is not willing to go so far. She is quite convinced of the existence of the film for several reasons. Apart from the references Cinema Almanac of China 1927, she notes an article published in HK in a 1924 New Bijou Theatre Newsletter, often overlooked for some reason or other. The latter reports: “A Russian [Brodsky?] arrived in Hong Kong in 1912 and cast Mr. Leung Siu-po in Stealing a Roast Duck, one of several slapstick films. Shortly after, Lai Man-wai was cast in Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife and The Ghost of the Pot Returns.”

Wong Ain-ling also cited the testimony of veteran filmmaker Moon Kwan, in both his 1976 book Unofficial History of the Chinese Cinema and his oral records with film historian Yu Mo-wan (as recorded in Yu’s Historical Account of HK Cinema, vol 1). Moon Kwan indicated that he watched the Roast Duck alongside Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife in Hollywood in 1917 (or perhaps 1915). In some detail, he recalled the story of the film and the cast, with Leung Siu-po in the role of the thief, Wong Chong-man as the hawker of roast ducks, and Lai Buk-hoi as the policeman.

As for the year of production, Wong finds 1909 quite shaky; 1912 as cited in the New Bijou Theatre article seems a bit closer. That date is also more consistent with the biography of Brodsky. She concluded her remarks by asking whether it is so important to have a celebration or centenary.

I was asked to sit on the panel as well. All I suggested was that there are problems with determining “first films” in any national cinema tradition. There are empirical difficulties—matters of fact, we might say. Most silent films are lost, and paper records are incomplete or destroyed, so it’s quite likely that any country’s earliest productions could be undocumented. Hence we often have to rely on memories, oral history, word of mouth, and collective opinion. Such seems to have been the case with Stealing a Roast Duck.

There are conceptual difficulties about firsts too. What will count as a film? There were many documentaries and newsreel films made in Hong Kong before 1909, some by Hong Kongers. Why are these not candidates for first films? Because, I suggested, we tend to think of “real films” as telling fictional stories by staging the events. Stealing a Roast Duck would fulfill that condition.

The first volume of the Hong Kong Film Archive filmography [4] has taken care to specify what conditions make something a first film in some respect. Chuang Tzu is called Hong Kong’s first “two-reel” film and its first “fiction” film. The Calamity of Money (1924) is described as the first Hong Kong film to be publicly shown in the colony. Rouge (1925) is labeled “Hong Kong’s first feature-length fiction film.” All of these films are, of course, currently lost.

I added that we select firsts on the basis of our assumptions and purposes. We assume that fiction films are more central instances of cinema than newsreels, or that films directed by Hong Kong people are more central instances than those directed by visitors or residents. And sometimes we want to celebrate cinema, so we create a pivotal anniversary: an example is the one hundredth anniversary of cinema (held in 1995, when we could also have done it in 1994). The effort to create a centenary, which in turn generates public interest in Hong Kong film, has settled on a story that suits that purpose.

It’s fun to imagine what a 1909 Stealing a Roast Duck might have been like. A one-reeler, maybe, built around a string of gags. Perhaps the thief makes many efforts to hitch the duck off the rack, before finally succeeding and being chased through the streets of Hong Kong by the cop. The duck becomes a football tossed from one party to another. . . .

More seriously, you have to be impressed with the care with which my fellow panelists exhumed and dissected their evidence. As usual, the closer you look, the more complicated any issue becomes. One of the pleasures of studying film history is that it can surprise us.

An excerpt from Brodsky’s Beautiful Japan is included on volume 1 of the DVD collection Treasures from American Film Archives [5]. A Guardian interview with Law Kar about Stealing a Roast Duck is here [6]. Thanks to Frank Bren for help with access to illustrations.

Law Kar, Wong Ain-ling, Li Cheuk-to, Frank Bren, DB.