Kristin here—

David and I are currently revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for a third edition due out next year. As part of the research, I’ve been watching two recent DVDs on the early history of sound and color. Both offer valuable resources for those teaching introductory film-history classes, as well as more specialized ones.

Twenty-five years ago, when I last taught a survey history class, the resources for teaching about the innovation of sound were discouragingly limited. The early Vitaphone shorts were as yet unrestored, with most of their accompanying discs damaged or lost. The most famous early sound films were mainly available in mediocre 16mm prints. Showing an “early” sound film often meant a René Clair classic from the early 1930s—a time when the transition to sound was well along, if not over. Le Million or Á nous la liberté demonstrated the artistry that an imaginative director could bring to the early sound cinema, but it wouldn’t give much idea of the struggle inventors and filmmakers went through to create the complex technology.

The same was true for pre-1935 color. There was no way to adequately survey the range of processes and experiments, from early hand painting and stenciling to two-strip Technicolor. The poor 16mm prints of early films often gave no real indication of what they had looked and sounded like when they were made.

Since then archivists have been intensively discovering and preserving films, and in some cases these have been released on DVD. Often these discs are simply collections of films, but documentaries incorporating short films and clips are becoming more common, especially since they make attractive television programs.

Discovering Cinema (Flicker Alley)/Les Premiere pas du cinéma (Lobster & histoire)

A two-DVD survey from the very active Lobster archive [1] in Paris devotes a disc each to sound (2003) and color (2004). Lobster is a private archive started in 1985 by two film enthusiasts, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange. (The website offers a choice of French or English text.) It began as an effort to discover lost films. Building on its success, Lobster has grown into a major resources for restoring films—both their own discoveries and commissions from other archives and from film companies.

David and I bought this set when it came out. The French boxed set offers a choice of French- or English-language versions. (It’s not region-coded, but it is PAL, which means it won’t play on NTSC players, the standard in the U.S. and some other countries.) The French version isn’t on the Amazon.fr site, but fnac [2] is offering it.

In September, 2007, the American version [3] was released by Flicker Alley [4]. This is another private archive, founded in 2002, also by an enthusiast, Jeffery Masino. The company hasn’t put out many titles yet, but the DVDs available so far are impressive. Flicker Alley collaborates with Turner on restorations, and presumably its catalogue will grow.

Each Lobster documentary is about 52 minutes long, and the supplements include a number of complete films.

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

There’s a quick run-through on color in pre-cinema devices: slides, peep shows, and topical toys. The next section gives a splendid demonstration of how stencils were used to hand-color films (such as the unidentified example above), as well as some briefer coverage of tinting and toning.

Moving to additive color systems, the film deals with Friese-Green’s early experiments, Charles Urban’s Kinemacolor, with its brief commercial success, Gaumont’s technically sophisticated Chronochrome, and various lenticular systems. Given that these attempts require special projection, the recreated examples given here are one of the few ways that we can see such films today. All of them proved dead ends, however, so they are of more interest for their technical ingenuity than for their ultimate impact.

The final part of the film turns to Technicolor, founded in 1915. The firm quickly turned away from its early additive experiments and settled on a subtractive system using two strips of film and later, in the 1930s, three strips—resulting in the vibrant hues that many people still think of as the acme of filmic color. “Movies Dream in Color” gives a brief but useful run-down of Technicolor’s progress, through its early two-strip successes like The Black Pirate through the exclusive contract with Disney in the 1932-36 period, and its triumph thereafter as the main color system of Hollywood. There is also some coverage of the two brands that combined all colors on a single negative, Kodachrome and Agfacolor, but the coverage essentially ends in 1939, before either had become widespread.

Incidentally, an in-depth study of Technicolor has recently been published: Scott Higgins’ Harnessing the Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s [5].

The filmmakers weave together interviews with a number of prominent archivists, including Paolo Cherchi Usai (co-founder of “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival and now director of Australia’s national archive) and Gian Luca Farinelli (director of the Cineteca di Bologna).

“Learning to Talk” (in the French set “Á la recherche du son”) uses the same group of experts and a somewhat similar three-part organization: “artistic sound” (that is, live sound during the projection of silent films), sound on disc, and sound on film.

The segment on live sound is excellent. It again starts with pre-cinema music and effects for magic-lantern shows and progresses to Reynaud’s hand-drawn Pantomimes lumineuses, with their specially written music. One highlight is documentary footage of a man demonstrating the use of an elaborate sound-effects box, with its brushes, cans of pebbles, and other crank-operated devices that simulated such actions as trains moving and crockery being smashed.

The sections devoted to sound-on-disc and sound-on-film are less well set forth, since the filmmakers try to cover many pioneers in France, the U.S., Germany, and Denmark. Again, several of the devices covered were novelties that led nowhere or that failed for lack of amplification, the use of non-standard film widths, and other reasons.

Once the story reaches the lengthy invention process of the two main American systems, Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone (using discs) and Fox’s Movietone (sound-on-film), it proceeds more clearly. “Learning to Talk” includes some of the Case and Sponable demo films, a Movietone News interview with Mussolini, and a clip from Don Juan. Presumably because of rights problems, no footage from The Jazz Singer is shown.

The bottom line is that the color disc strikes me as the more useful for teachers. The sound one gives good coverage, but again many of the systems discussed are not historically significant to anyone but specialists. For a history of that deals largely with the American innovation of sound, one can now turn to a superb recent DVD.

A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures: The Beginning: 1876-1932 (UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Rick Chace Foundation).

This disc originated in a lecture on early sound by Robert Gitt [6], who has long been the preservation officer for UCLA’s film archive. Gitt has supervised on the restoration of many important films. In 1991 his team launched the Vitaphone Project. Vitaphone, Warner Bros.’s commercially successful sound system of the 1926-31 period, used phonograph records rather than optical tracks on the film strip. Over the decades many of those discs were damaged or separated from the original reels, and the Vitaphone shorts sat in their cans, reduced to silence.

Gitt and company set about finding as many discs for the surviving Vitaphone films as they could. Over the years they were amazingly successful in tracking them down and rejoining sound and image in a sound-on-film format that can be shown on modern projectors. You can trace the progress of the project since its beginning through its online newsletter [7], which currently runs from fall, 1991 to winter, 2007/08.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

The result offers an extraordinary array of clips that teachers could draw upon even if they don’t have time to show the entire lengthy documentary. For Vitaphone there are some of the early shorts, the entire duel scene from Don Juan, extended excerpts from The Better ‘Ole, Old San Francisco, Lights of New York, and others. For Fox Movietone there are scenes from 7th Heaven and Sunrise, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s charming appearance in an issue of Movietone News.

Despite some lively moments, many of the early sound films are slow and clunky, due to the limitations of the available equipment. Gitt balances them by ending with some familiar examples of the imaginative early use of the new technique: the “Paris, Please Stay the Same” number from Lubitsch’s The Love Parade, a generous excerpt from Mamoulian’s Applause, and a portion of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (which, be warned, gives away the ending). Teachers whose schedules don’t permit them to devote precious screening time to an early sound feature can give their students a reasonably good sense of the transitional period with such clips.

We’ve all heard the stories about how certain actors’ careers were destroyed by sound, but for the teacher there’s again the problem of how to demonstrate this to classes. Gitt has filled this need as well. Among the bonuses (which are few because so much is included in the film), there is one on the fates of actors. For each Gitt supplies both a clip of the actor in a silent film and in a sound one. The actors whose careers took a nose dive in sound films are represented by Rod La Roque, Norma Talmadge, John Gilbert, and Charles Farrell. Those who successfully made the transition are Ronald Colman, Joan Crawford, William Powell, and Laurel and Hardy. Gitt makes plausible cases why the public responded to each actor as it did.

As the disc’s title implies, it is intended to be part of a series of three documentaries that will cover the entire century. If Gitt continues to get access to the sort of material he presents here, the result should be an impressive overview of the subject and a boon to educators. If in the 1970s and 1980s we had dreamt up our ideal documentary subject for teaching early sound, it would have looked a lot like A Century of Sound—except we couldn’t have imagined all the material that existed in the vaults, waiting to be found and restored.

A Century of Sound is not available commercially. Educators and researchers can request a free copy (with a $10 shipping charge) by downloading a pdf form here [8].

The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros.)

Released this past October, this three-disc deluxe set [9] marks the first time that The Jazz Singer has been on DVD. (Legally, that is; there was apparently a Chinese bootleg.) It also includes numerous supplements, some of which might be useful for teaching the introduction of sound.

The first disc contains the restored print of The Jazz Singer, a complete version of Al Jolson’s Vitaphone short, A Plantation Act, and some other shorts. One of these is the classic Tex Avery cartoon, I Love to Singa, inspired by The Jazz Singer and starring “Owl Jolson.”

An 85-minute documentary, The Dawn of Sound: How Movies Learned to Talk is the main item on the second disc. It was made by Turner Entertainment and bears a copyright date of 2007. Like so many TV shows, it doesn’t trust enough in the inherent interest of its topic. Rather than explaining the sound systems clearly by type, the writers have opted to try and stress the four Warner brothers as interesting personalities (not very successfully) and the intense competition among the sound systems in the late 1920s. The opening third cuts together too many brief, unidentified film clips and talking-heads comments, which doesn’t make for a coherent introduction to the topic. The production of the Vitaphone shorts is not well explained, though the film does point out that the shorts were more influential than Don Juan in making the new process appeal to audiences. There are excerpts from the main early Warners sound films, as well as a section on actors who succeeded or failed in talkies.

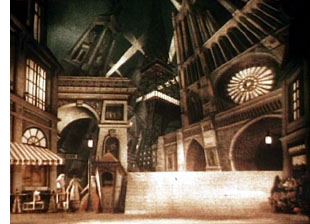

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

The rest of the disc consists mainly of some older documentaries on early sound made by Warner Bros. One, The Voice from the Screen (1926) was intended as a demonstration of Vitaphone for technicians. The presenter is not, to say the least, charismatic, and it’s obvious why Discovering Cinema and A Century of Sound use only excerpts. Nice to have it complete, but students wouldn’t sit still for the whole thing. The Voice that Thrilled the World was directed by Jean Negulescu in 1943, on the occasion of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences adding a best-sound Oscar—the first of which happened to go to Warners’ Yankee Doodle Dandy. This short seems to be the source for the staged footage of early sound breakthroughs that show up, unidentified, in The Dawn of Sound and the other documentaries. Not surprisingly, The Voice that Thrilled the World primarily hypes the Vitaphone process.

“Okay for Sound” (1946) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Don Juan’s premiere, and it recycles a lot of material from the 1943 short. Like The Voice that Thrilled the World, it was a theatrical short, intended as much to promote current Warners’ films as to celebrate the studio’s past triumphs. The film handily includes an extended clip of Jolson singing the saccharine “Sonny Boy” number in The Singing Fool (1928).

(A companion book with a slightly different title, “Okay for Sound!” was published in 1946. It’s a picture history of sound. The photos are not well produced, and many are just publicity stills from films. It does contain quite a few photos of sound equipment. It turns up with surprising frequency in used-book stores. The phrase, by the way, is what recordists would call out to indicate to directors when the sound was operating and the action could start–their equivalent of the camera operators’ “Speed!”)

When the Talkies Were Young (1955) is an odd, low-budget documentary that consists of fairly extended clips from some early Warners’ talkies: Sinners’ Holiday (1930), 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), Night Nurse (1931), Five Star Final (1931), and Svengali (1931). These aren’t bad, though unfortunately the narrator occasionally interjects comments during the action.

The third disc contains over three and a half hours of restored Vitaphone shorts, a treasure trove for teachers who want to show some examples of these. The first one, Behind the Lines (1926), is the example we use in our box on “Early Sound Technology and the Classical Style” in Chapter 9 of Film History: An Introduction (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5, p. 197 in the second edition).

If I had to make a choice of just one of these three DVD releases in looking for clips for a unit on early sound, I would favor A Century of Sound as having the best organized presentation and the most useful set of excerpts. The “Learning to Talk” disc could be useful as a briefer, self-contained teaching tool. The Jazz Singer package is a bit of a hodgepodge, but educators who want to deal with early sound in depth could pluck out some very useful additional material from it.

A May 12, 1925 Case test with Gus Visser and his duck singing a duet of “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me.” (Added to the National Film Registry in 2002 and included in both Learning to Talk and A Century of Sound.)